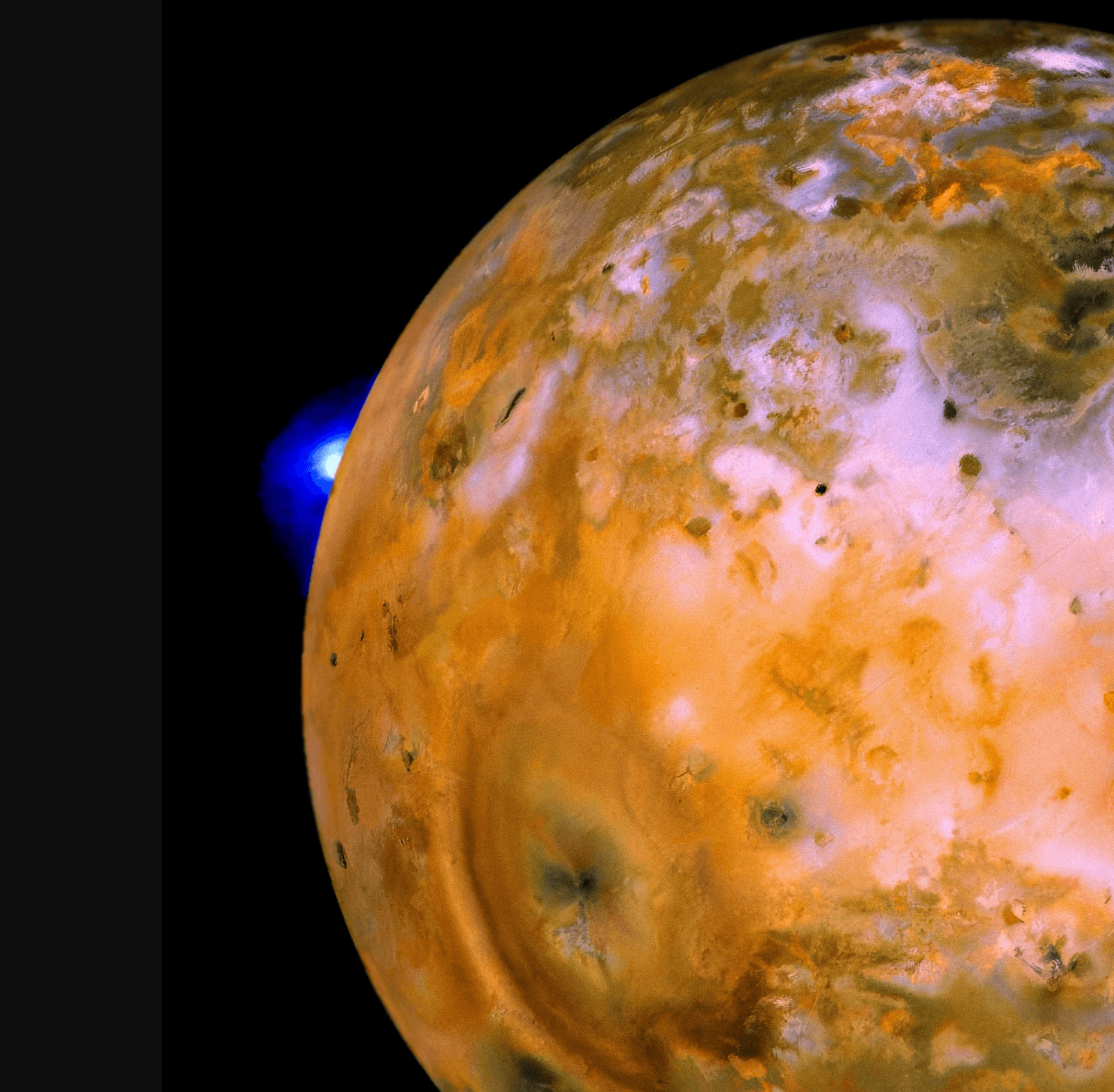

Radar measurements of Venus‘s surface reveal the remains of many volcanic eruptions. One type of feature, known as a pancake dome, has a very flat top and steep sides; one dome, Narina Tholus, is over 140 kilometers wide. Since their discovery, scientists have been puzzling out how such domes could form. A recent study suggests that the Venusian surface’s elasticity plays a role.

According to current models, the pancake domes are gravity currents (like a cold draft under your door, an avalanche, or the Boston Molasses Flood), albeit ones so viscous that they may require hundreds of thousands of Earth-years to settle. Researchers found that their simulated pancake domes best matched measurements from Venus when the lava was about 2.5 times denser than water and flowed over a flexible crust.

We might have more data to support (or refute) the study’s conclusions soon, but only if NASA’s VERITAS mission to Venus is not cancelled. (Image credit: NASA; research credit: M. Borelli et al.; via Gizmodo)