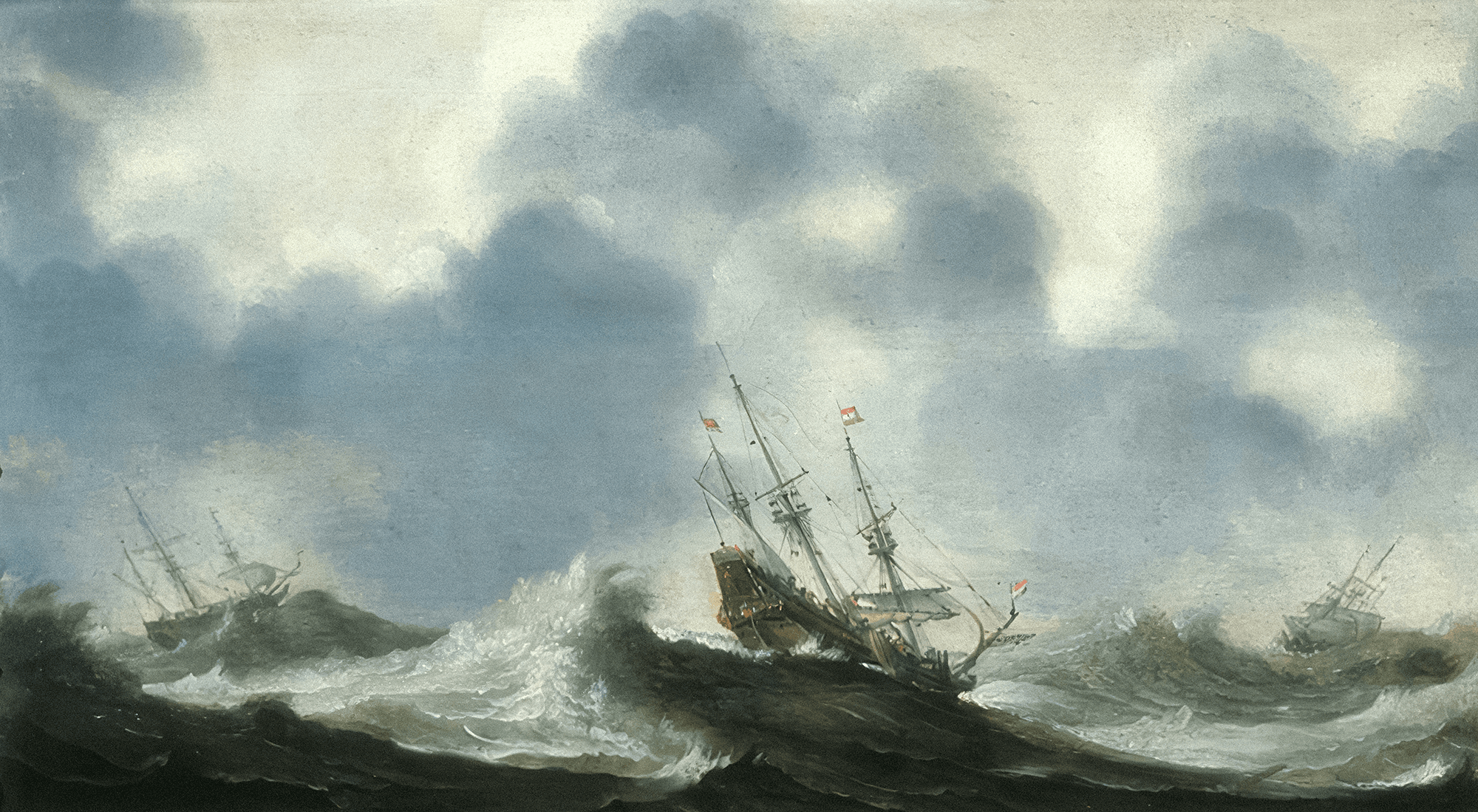

Rogue waves were once the stuff of nautical legend. Tales of giant lone waves were considered sailors’ tall tales, until an oil rig in the North Sea was hit by a 25.6-meter wave on 1 January 1995. The wave was more than twice the height of any others around it and much steeper, too. Since then, scientists have been working to understand how and why these rogue waves form.

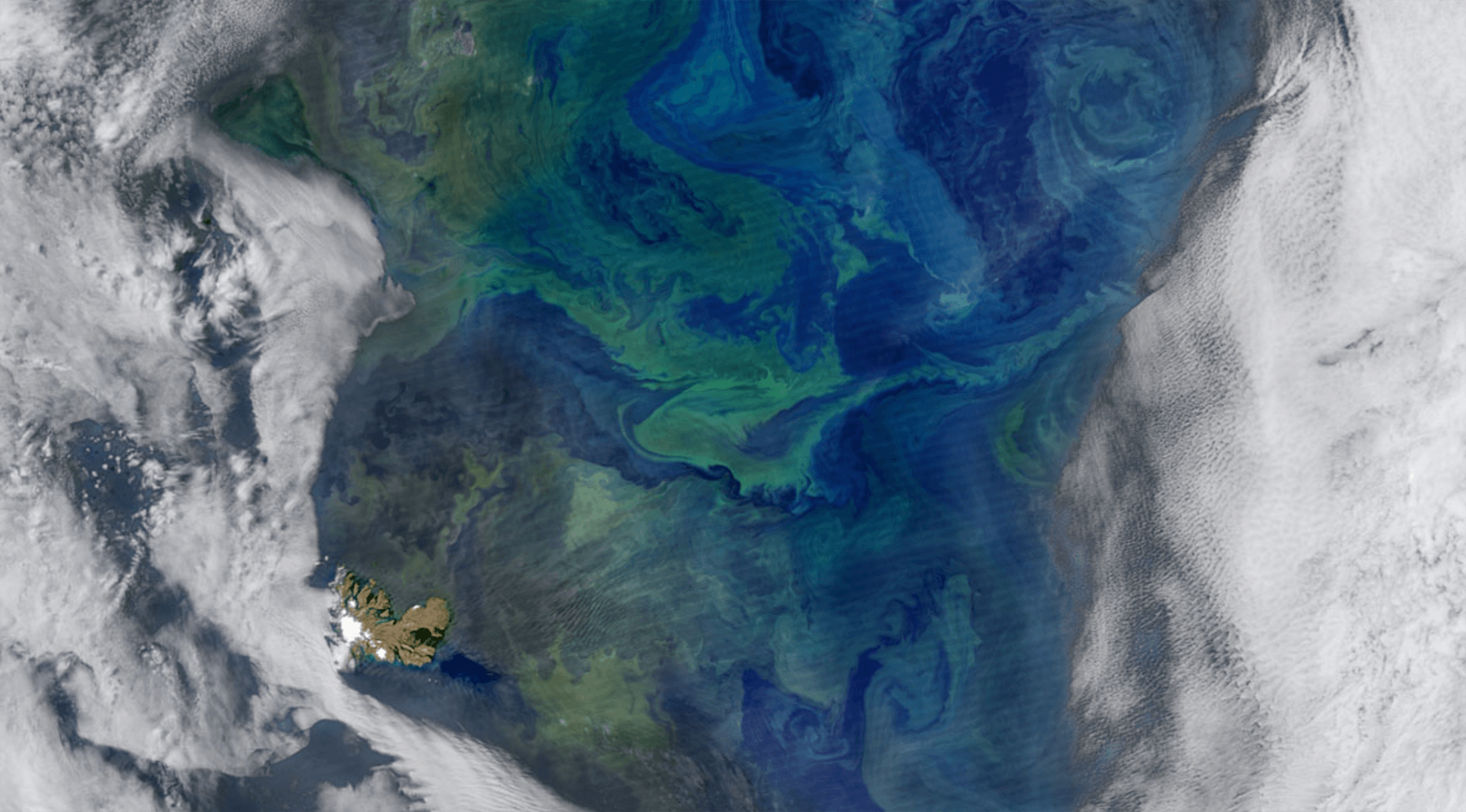

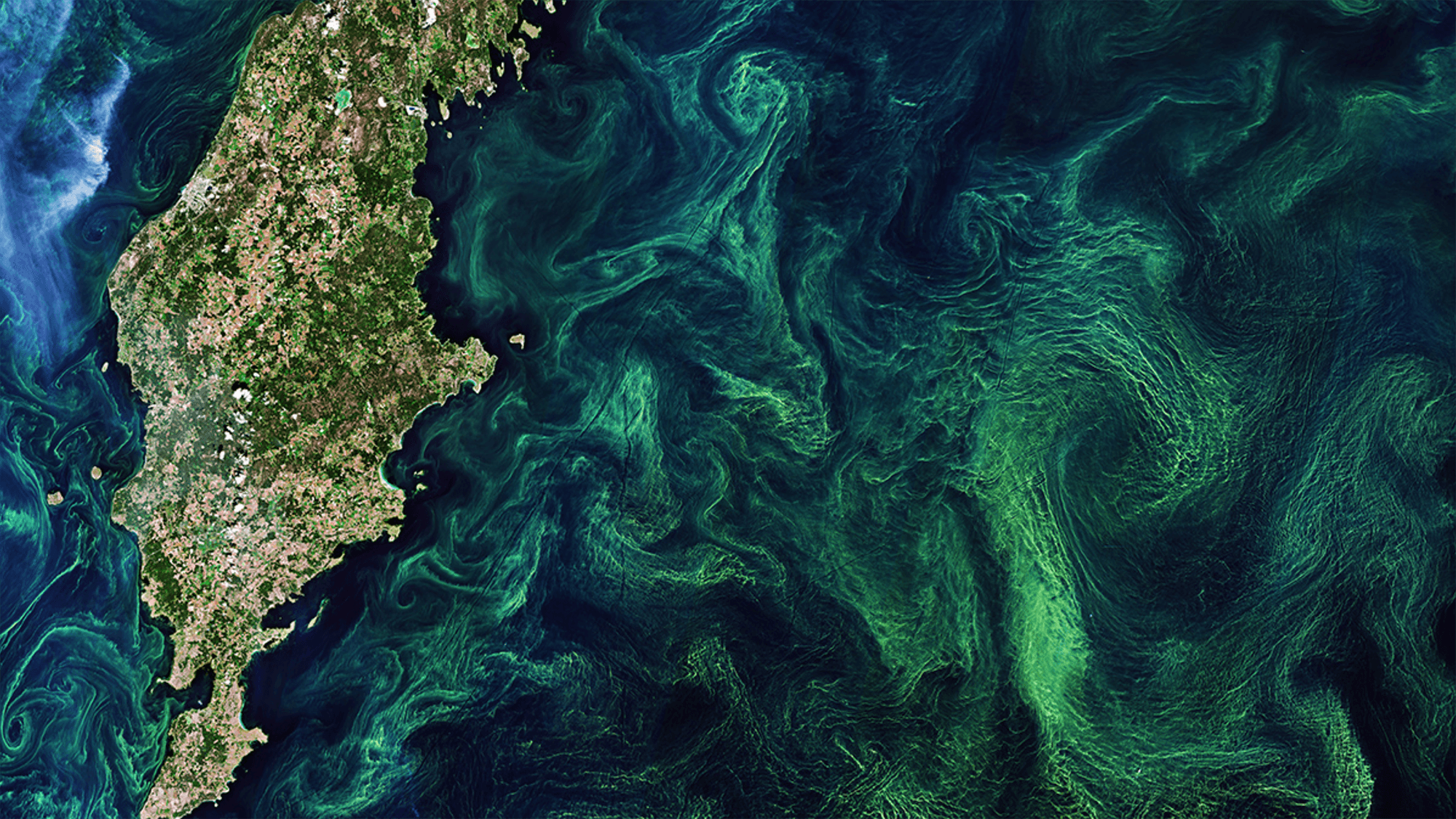

A recent study, like many others, attributes rogue waves to the subtle nonlinearities of ocean waves, which don’t match a smooth sinusoid even though they are sometimes modeled that way. When it comes to rogue waves, the sharpness of a wave’s peak and flattening of its trough affect whether waves come together into a lone giant.

The study is based on 18 years worth of wave data collected at an offshore platform in the North Sea. With such an extensive data set, researchers were able to find patterns in the waves that precede the arrival of a rogue wave. That’s an important step toward being able to predict a rogue wave, which would help protect platforms, ships, and personnel. (Image credit: C. Wou; research credit: S. Knobler et al.; via SciAm)