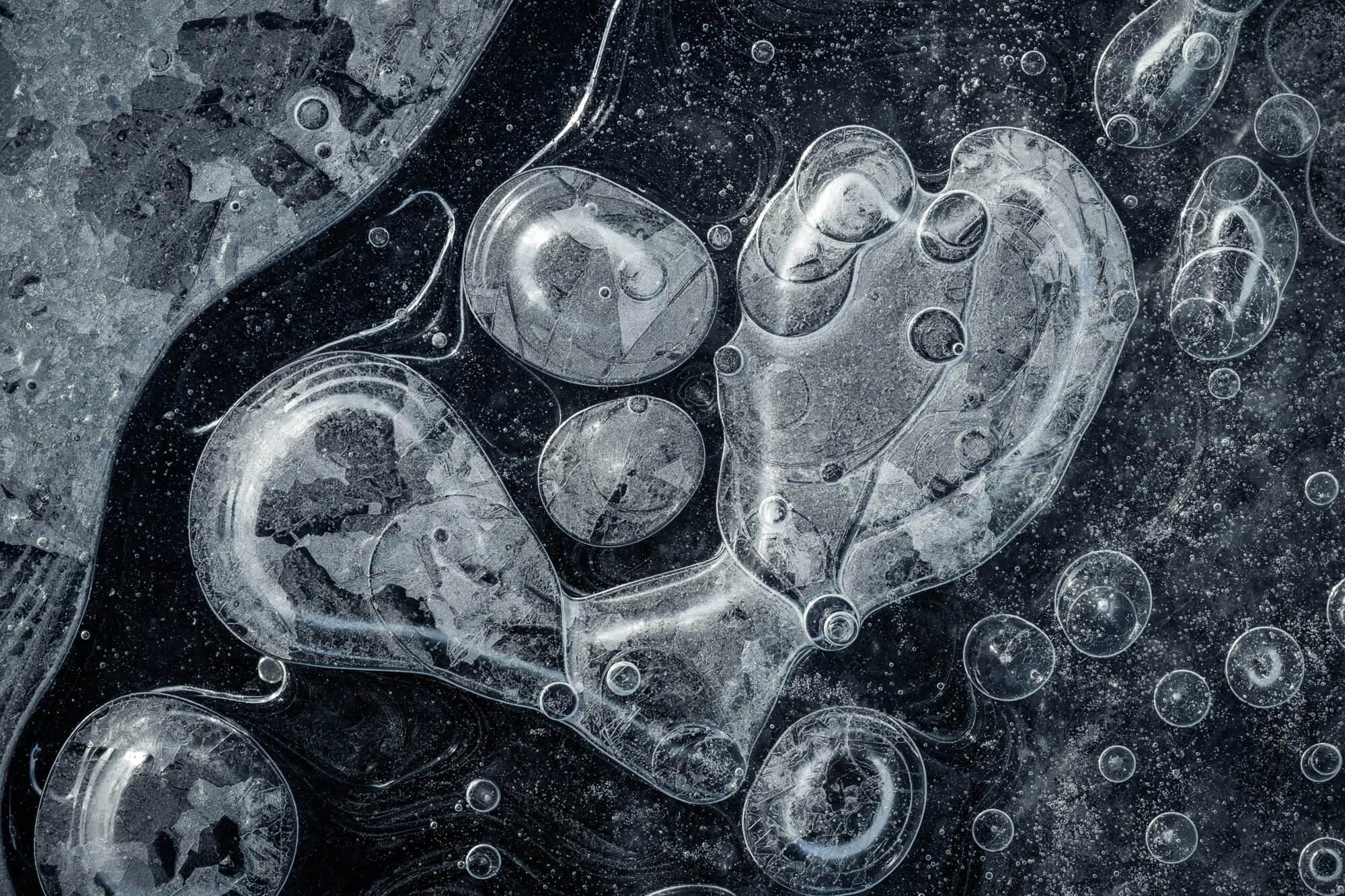

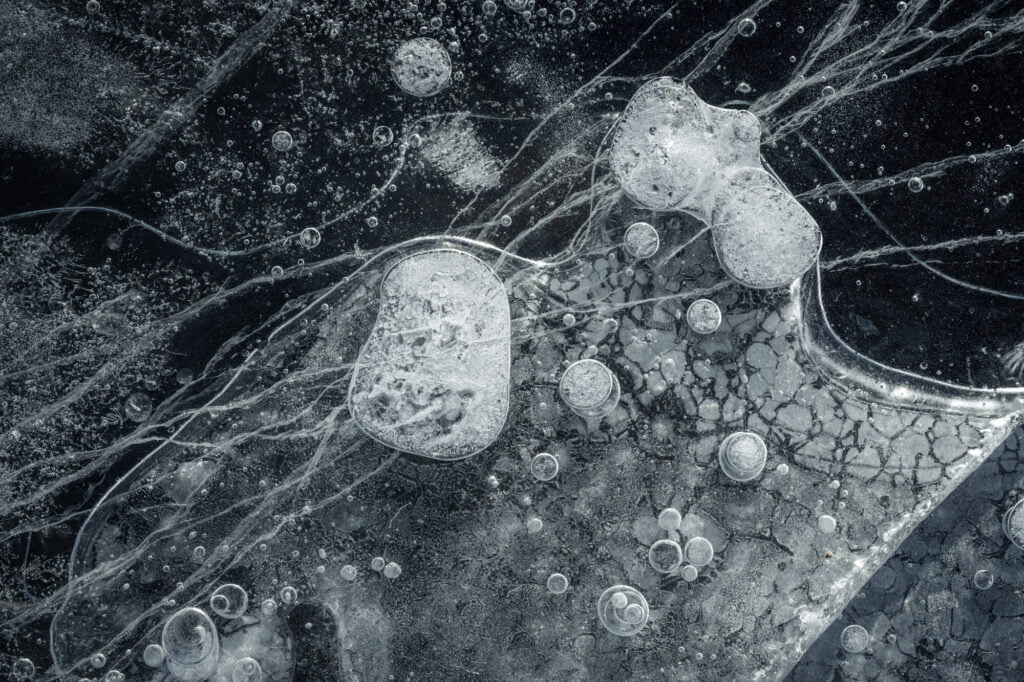

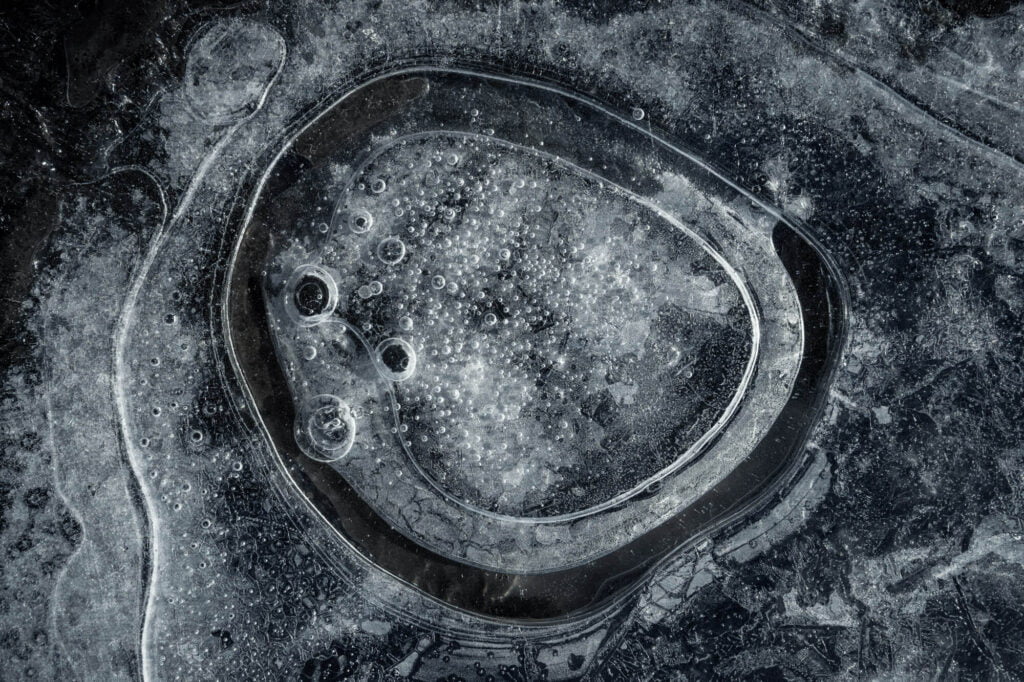

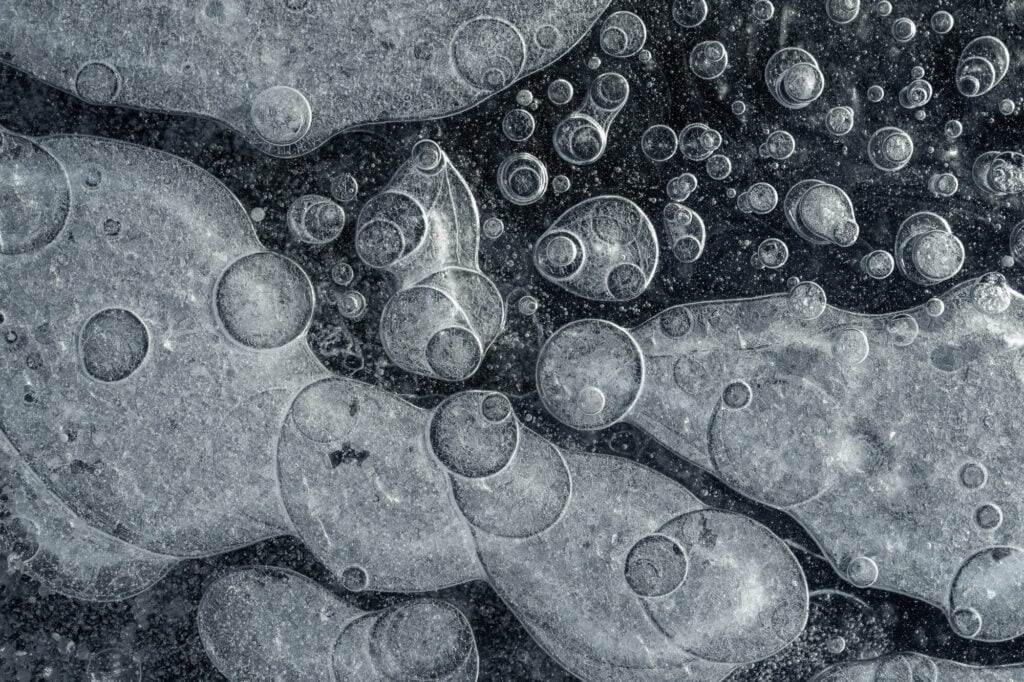

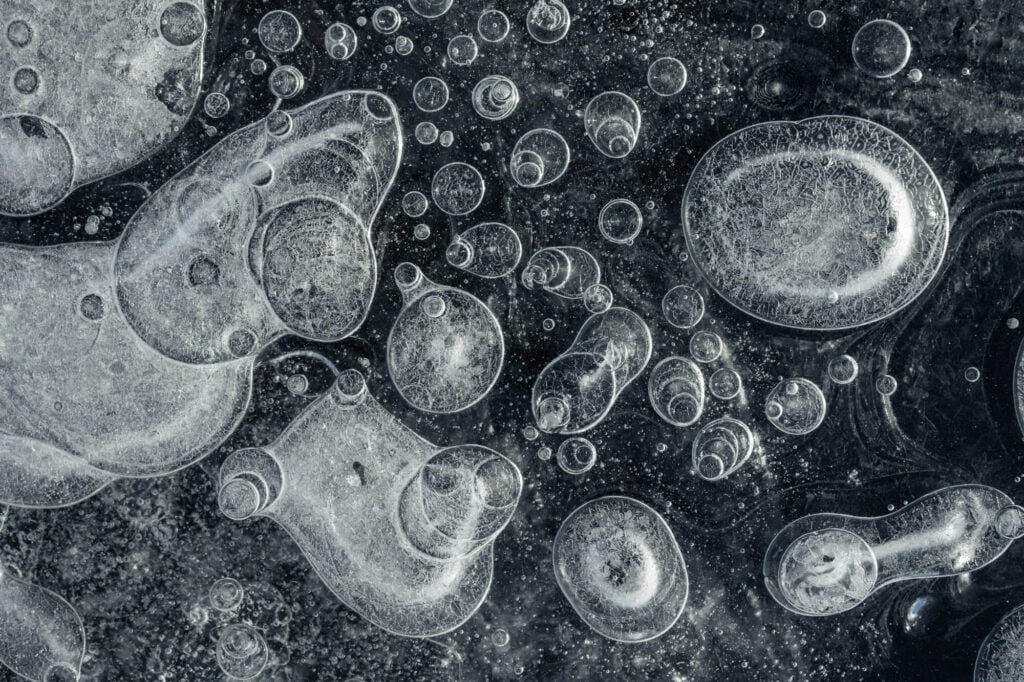

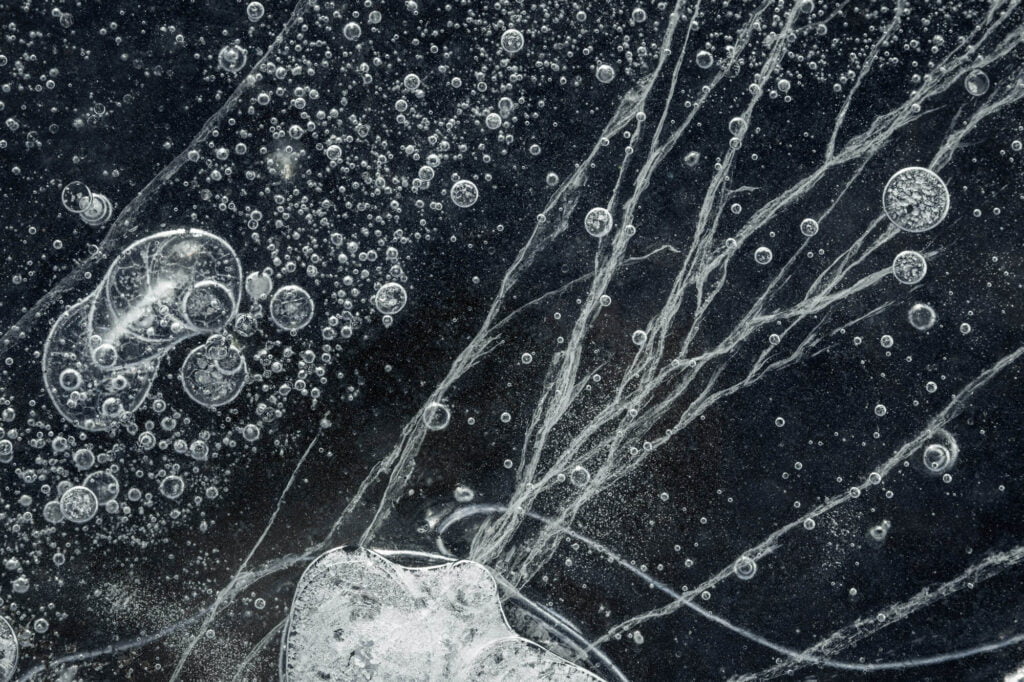

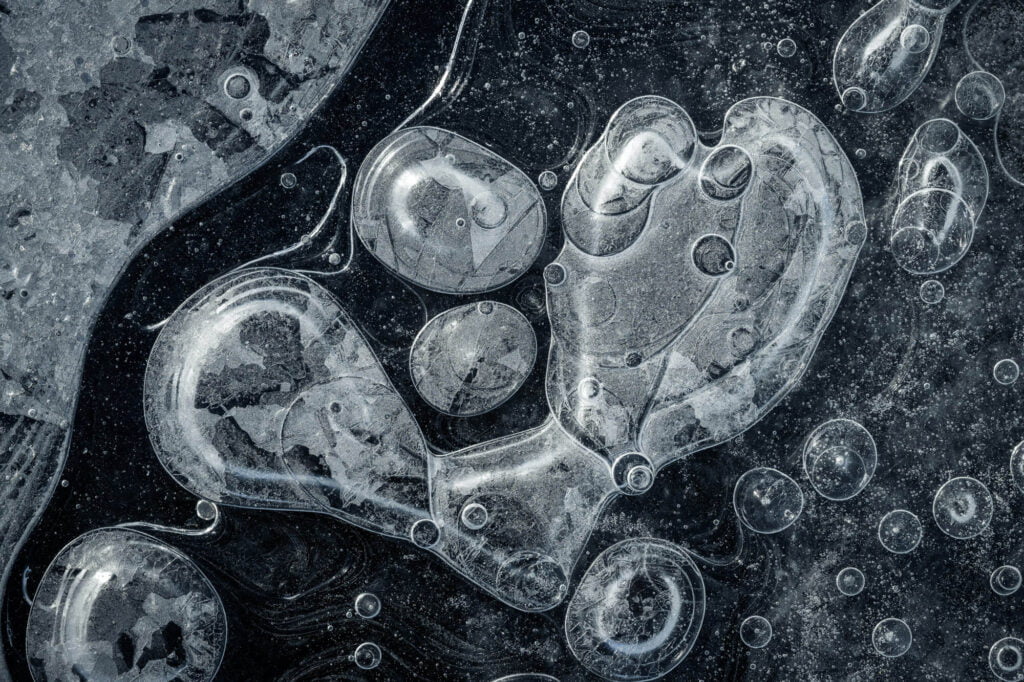

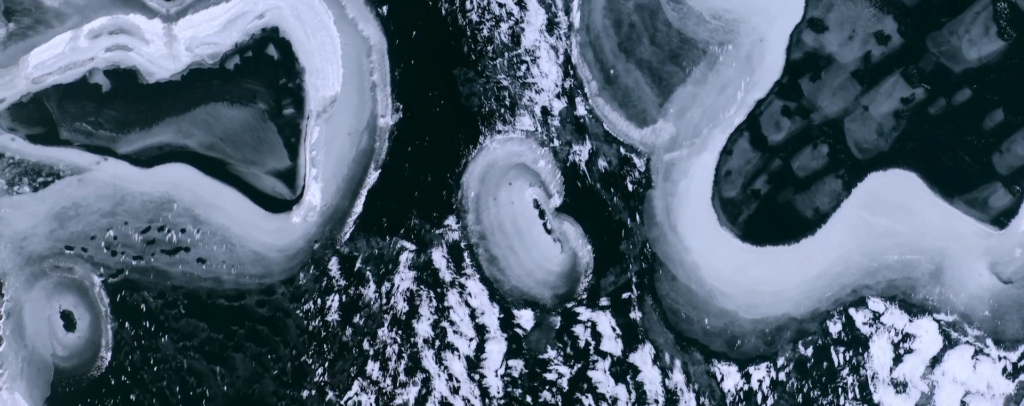

On lake bottoms, decaying matter produces methane and other gases that get caught as bubbles when the water freezes. In liquid form, water is excellent at dissolving gases, but they come out of solution when the molecules freeze. In the arctic, these bubbles form wild, layered patterns like these captured by photographer Jan Erik Waider in a lake on the edge of Iceland’s Skaftafellsjökull glacier. Unlike the bubbles that form in our fridges’ icemakers, these bubbles are large enough that they take on complicated shapes. I especially love the ones that leave a visible trail of where the bubble shifted during the freezing process. (Image credit: J. Waider; via Colossal)

Tag: ice

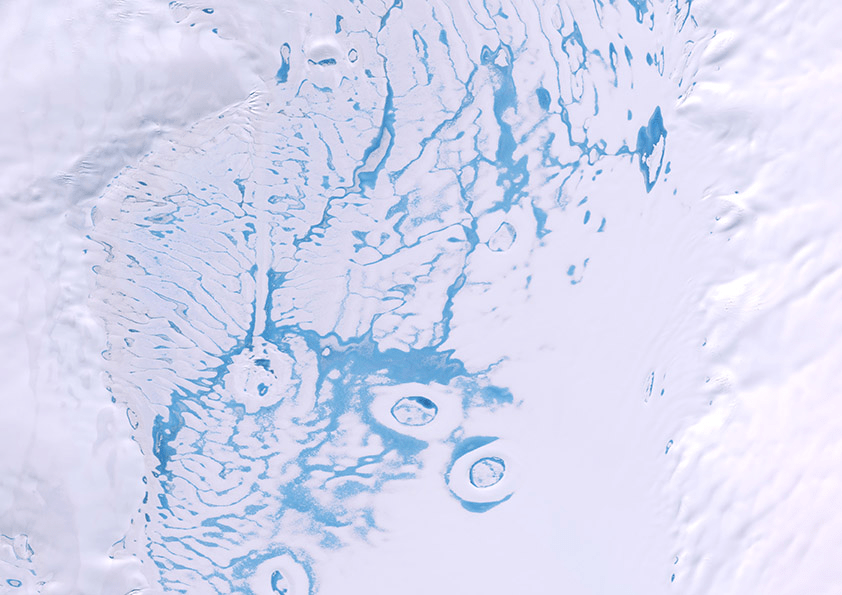

Slushy Snow Affects Antarctic Ice Melt

More than a tenth of Antarctica’s ice projects out over the sea; this ice shelf preserves glacial ice that would otherwise fall into the Southern Ocean and raise global sea levels. But austral summers eat away at the ice, leaving meltwater collected in ponds (visible above in bright blue) and in harder-to-spot slush. Researchers taught a machine-learning algorithm to identify slush and ponds in satellite images, then used the algorithm to analyze nine years’ worth of imagery.

The group found that slush makes up about 57% of the overall meltwater. It is also darker than pure snow, absorbing more sunlight and leading to more melting. Many climate models currently neglect slush, and the authors warn that, without it, models will underestimate how much the ice is melting and predict that the ice is more stable than it truly is. (Image credit: Copernicus Sentinel/R. Dell; research credit: R. Dell et al.; via Physics Today)

“Serenity”

Peering from directly above, landscapes take on a whole different aspect. That idea is the heart of Vadim Sherbakov’s “Serenity,” filmed by drone. From seething waters and meandering rivers to eroded landscapes and twisting ice, there’s lots of fluid dynamics on display here. (Video and image credit: V. Sherbakov)

Light Pillars

These lovely pillars of light over the Mongolian grasslands are the result of tiny, suspended ice crystals. With the right weather conditions, ice crystals can align so that their largest faces are roughly parallel to the ground. In this orientation, the crystals collect and reflect artificial lights from the ground into these towering light pillars. It’s worth noting that the pillars aren’t located directly above the light source; instead, the column of crystals will lie roughly halfway between the light source and the observer. Next time you’re out on a cold winter night, see if you can find one! (Image credit: N. D. Liao; via APOD)

“-37F Winter in Yellowstone”

Yellowstone National Park is always fascinating and surreal, but especially so in winter when volcanically-heated geysers and springs meet frigid, snowy weather. This short film from Drew Simms shows the park and its wildlife in the depths of winter. The bison rely on thick, shaggy fur coats to trap heat and keep dry. Steam and mist mingle around springs and giant plumes rise from geysers. What a strange and beautiful landscape! (Video and image credit: D. Simms)

“Winter”

Little by little, snow and ice transform the landscape in Jamie Scott’s film “Winter.” From individual snowflakes to entire forest vistas, the timelapses showcase how winter remakes every surface in its image. The growing icicles show freezing in action, but I especially love seeing the “flow” brought about by progressively greater snowfall. Tree limbs bow, shrubs swell, and riverbanks contract as the snow gets thicker. And that final shot that pulls out from single snowflakes to the entire forest? Stunning! (Video and image credit: J. Scott et al.; via Colossal)

Flipping Ice

In nature ice is ever-changing — growing, shrinking, and shifting. This poster illustrates that with a cylinder of ice floating in room temperature water. As the ice melts, it flips over into a new orientation, stays that way for a time, and then shifts again, as seen in the series of blue images. This flipping results from the melting flows around the ice, illustrated in the colorful central photo. This color schlieren image shows dense plumes of cold meltwater sinking beneath the ice. As that cold water drips down the sides of the ice, it leaves behind a wavy, patterned surface. Eventually, melting from the bottom of the ice leaves the remaining ice top-heavy, which triggers a flip into a more stable orientation. (Image and research credit: B. Johnson et al.)

Ice Damages With Liquid Veins

Water expands when it freezes, a fact that’s often blamed for ice-cracked roads. But expansion isn’t what gives ice its destructive power. In fact, liquids that contract when freezing also break up materials like pavement and concrete. A recent study pinpoints veins between ice crystals as the source of this infrastructure-cracking power.

Ice doesn’t like to stick on most surfaces, so when it forms, there’s often a narrow gap between the ice and a solid surface. That gap fills with water, and that water, it turns out, doesn’t just sit there. Instead, grooves between ice crystals act like tiny straws that are frigid on the icy end and warmer on the end connected to water. As ice forms on the cold end, it creates a negative pressure gradient that draws liquid up the groove. This ‘cryosuction’ keeps pumping water into the ice, where it freezes and further expands the icy zone, as seen in the image below.

Under a microscope, fluorescent particles show water (right side) getting pulled into an ice groove (left). If the ice is made up of a single crystal, this growth rate is very slow. But most ice is polycrystalline — made up of many crystals, all separated by these liquid-filled grooves. That, researchers found, is a recipe for fast growth and quickly-expanding ice capable of breaking concrete and other structures. (Image credits: pothole – I. Taylor, experiment – D. Gerber et al.; research credit: D. Gerber et al.; via APS Physics)

An August Arc

In summer, the fjords of Greenland are littered with ice, but in August 2023, satellites caught an odd interloper. See the thin white arc spanning the fjord in the photo above? Scientists suspect this ephemeral feature was a wave caused by a large iceberg calving off the glacier on the right. When large chunks of ice fall into the water, they can cause distinctive waves that travel out from the point of impact.

Another possible mechanism is an underwater plume. In Greenland’s fjords, such plumes are sometimes formed from freshwater melting below the glacier. When that water rises to the surface, it can push ice. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

“Black Ice”

Ice, black ink, and flowers combine in filmmaker Christopher Dormoy’s “Black Ice.” Filmed during the COVID-19 lockdowns, the video is an exploration of the creativity one can achieve when constrained. I especially enjoy seeing the tiny bubbles trapped in the ice escape as ink billows past, and the views of ice tunnels invaded by ink are incredibly cool. For a behind-the-scenes look at how Dormoy achieved many of the shots, see this video. (Video and image credit: C. Dormoy)