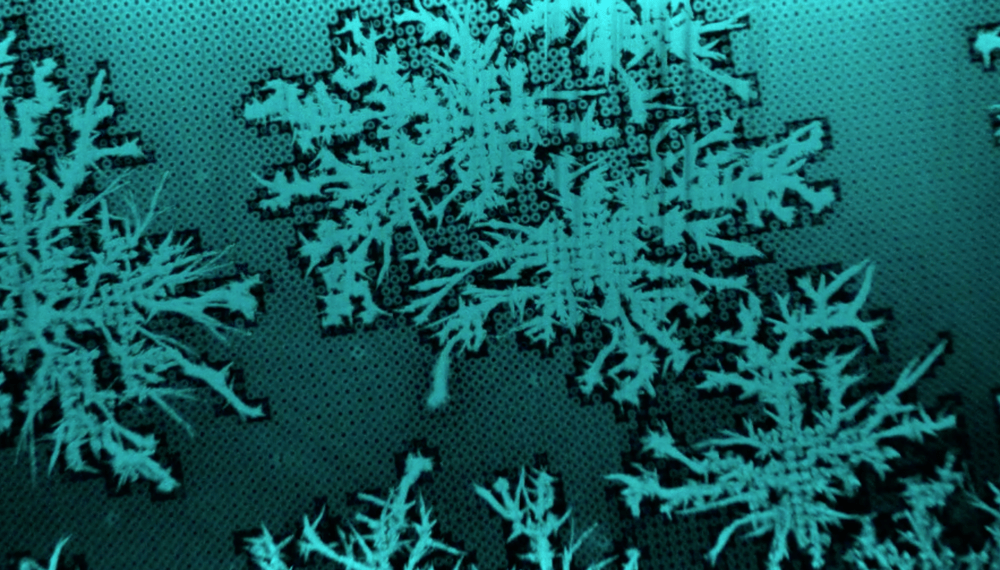

Frost forms hexagonal columns on a wooden rail in this microphotograph by Gregory B. Murray. Like in snowflakes, when water molecules freeze they position themselves to form six-sided crystals. From this perspective, it looks like a miniature version of the Giant’s Causeway. (Image credit: G. Murray; via Ars Technica)

Tag: frost

Spreading Frost

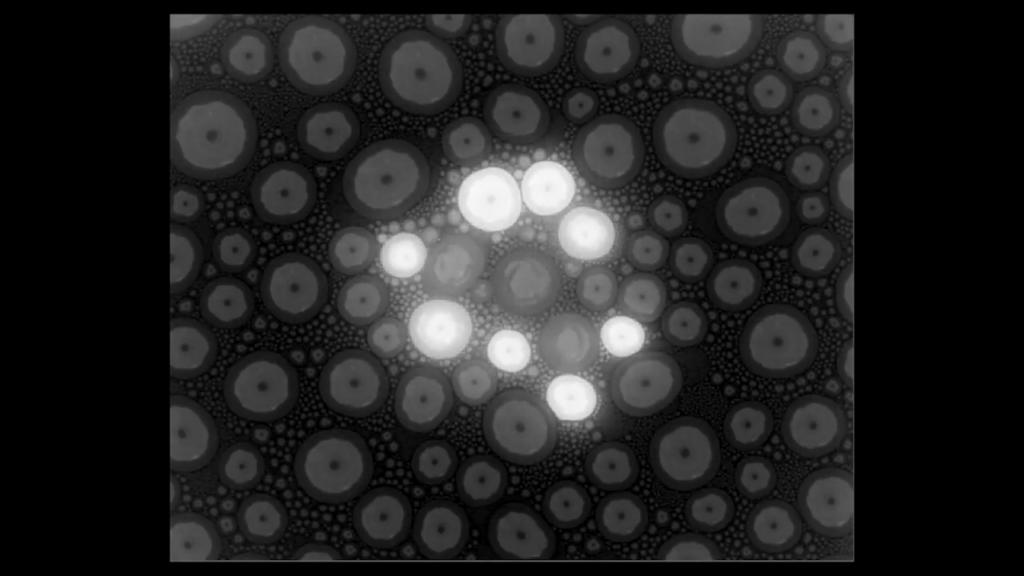

Condensation forms beads of water on a surface. When suddenly cooled, those drops begin to freeze into frost. This video looks at the process in optical and in infrared, revealing the patterns of spreading frost and the tiny ice bridges that link one freezing drop to the next. (Video and image credit: D. Paulovics et al.)

Fractal Frost

As nightly temperatures drop in the northern latitudes, many of us are beginning to wake up to frosty patterns on leaves, windows, and cars. Frost‘s spread is a complex dance between evaporation and nucleation, as seen in this recent study.

Here, researchers watched frost grow on a surface covered in 30-micrometer-wide micropillars. The pillars serve as anchor points for droplets, making frosting easier to observe. At low humidity levels (Image 1), droplets evaporate so quickly that frost regions remain isolated and do not interact. At high humidity levels (Image 3), on the other hand, the droplets evaporate so slowly that they’re able to poach water vapor from their neighbors to form frost spikes. When a spike touches another droplet, it freezes the region almost instantly. As a result, the frost spreads quickly and covers nearly every part of the surface. At intermediate humidity levels (Image 2), though, this frost chain reaction and evaporation compete, causing the frost to grow in fractals. (Image and research credit: L. Hauer et al.; via APS Physics)

Jumping Frost

Liquid water is easily electrically charged, due to its polar nature. That’s why rubbing a comb is enough to deflect a stream of water. Ice is harder to charge, but it can happen, especially when there are temperature gradients across the ice.

That’s the key behind this study of jumping frost. When ice crystals grow on a surface much colder than their surroundings, positive charges gather in the colder region, leaving the dendritic branches of the ice negatively charged. When researchers brought liquid water near the charged ice crystals, the water became charged, too. Positive charges in the water attracted the negatively-charged dendrites, causing the ice crystals to jump off the surface.

Studies like this help us better understand cloud and rain formation and may one day lead to new ways of de-icing surfaces. (Image credit: frost – Miriams-Fotos, figure – R. Mukherjee et al.; research credit: R. Mukherjee et al.; via ChemBites; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

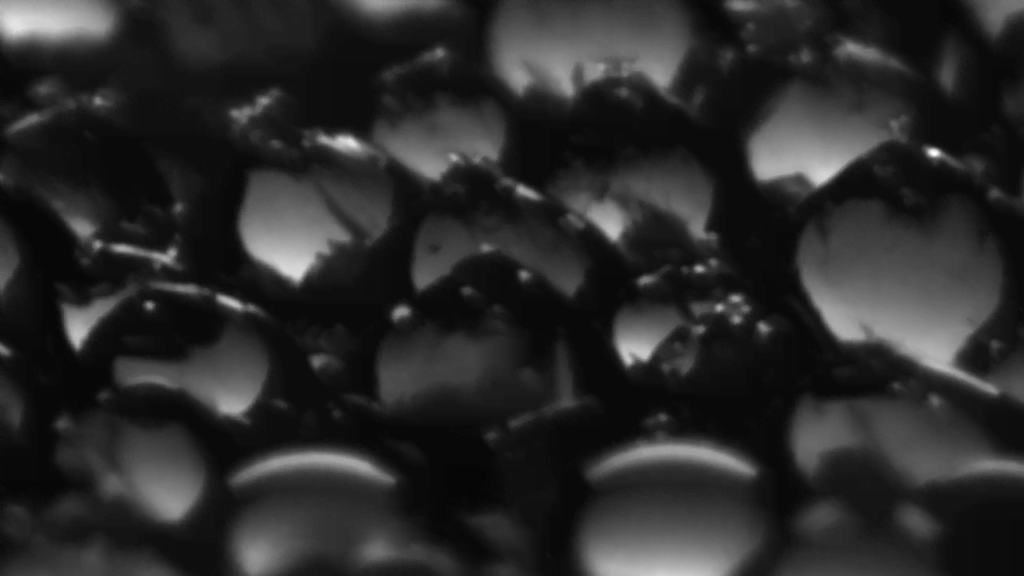

Frost Spreading

Frost typically forms when supercooled droplets of water scattered across a surface freeze together. The freezing spreads via tiny ice bridges that link droplets together into a frozen network. The animation above shows this process in action. Freezing starts in a droplet off-screen on the right and quickly spreads. Watch carefully, and you can see the ice bridges growing toward the unfrozen droplets. This is because the ice bridges are fed by water vapor evaporating from the droplets. If one can spread the droplets far enough from one another, it’s possible for a droplet to evaporate completely before the ice bridge reaches it, thereby disrupting the spread of frost. (Video credit: J. Boreyko et al.; research paper)

Reader Question: Frosty Cars

Reader Mike L asks:

Why do I never see frost on my car when I park in a detached garage or under a carport?Great question! Frost forms on surfaces when their temperature drops below the freezing point of water and the dew point of the surrounding air. The water vapor in the air gets deposited as a solid directly; this is called deposition. This means that the surface–in this case your car–has to be colder than the nearby air. Neither conduction nor convection of heat between your car and the surrounding air can cause this drop; heat transfer between your car and the surrounding air would tend to make them the same temperature, not make the car colder than the air. The third–and typically least effective–type of heat transfer, radiation, is the answer because it allows heat transfer between two objects that are not in direct contact like the air and car are.

Frost typically forms on still, clear nights with little clouds or wind. A car sitting beneath a clear night sky will radiate heat out into space. Since space is much, much colder than the air, this radiation cooling to space allows the car’s surface temperature to drop below that of the surrounding air, which is not a good radiator by comparison. On a night with little wind (and thus little convection), this radiation cooling can be quite effective. Frost will tend not to form on one’s car under a carport because the car is sheltered from the night sky, blocking such radiative cooling. Having a tree or house blocking the car from the night sky is also effective at preventing frost formation. (Photo credit: N. Sharp; with thanks to Keri B and Jerry N for the meteorological assistance)

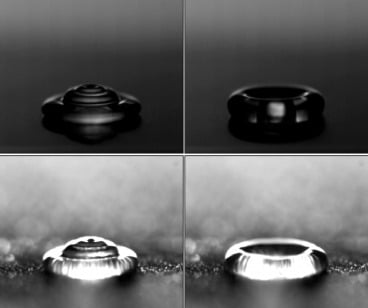

Frosting on Superhydrophobic Surfaces

Icing on airplane wings can be disastrous for lift and control, and thus how ice initially forms on a wing is an active area of research. New work shows that superhydrophobic (water-fearing) surfaces may actually promote ice buildup. Superhydrophobic surfaces are prone to frosting–collecting ice that forms directly from a vaporous state–and that fine layer of frost is conducive to further ice buildup from a liquid state. The photo above shows a water droplet striking a dry superhydrophobic surface (top) and a frosted superhydrophobic surface (bottom). (via Gizmodo) #