Few animals can compete with a peregrine falcon for pure speed. There is evidence that, when diving, the falcon can reach speeds upward of 200 mph (320 kph). That the birds can achieve this by pulling their wings back into a low-drag profile is impressive, but the control they exert to do so is even more astounding. The placement and acuity of a falcon’s eyes would require tilting its head roughly 40 degrees if diving straight down on its prey. Such asymmetry increases their drag by more than 50% and creates a torque that yaws the bird. Instead, as seen in the video above, the falcon keeps its head straight and flies in a spiral-like dive, allowing it to maintain sight contact with its target and maximizing its speed despite the extended dive. (Video credit: BBC; research credit: V. A. Tucker)

Tag: drag reduction

Hot Items Sink Faster

This combined video shows the fall of a heated centimeter-sized steel sphere through water. From left to right, the sphere is at 25 degrees C (left), 110 degrees C (middle), and 180 degrees C, demonstrating how the Leidenfrost effect–which vaporizes the water in immediate contact with the sphere–can substantially reduce the drag on a submerged object. In the middle video, the vaporization of the water around the sphere is sporadic and incomplete, only slightly reducing the sphere’s drag relative to the room temperature case. The much hotter sphere on the right, however, has a complete layer of vapor surrounding it, allowing it to travel through a gas rather than the denser liquid. (Video credit: I. Vakarelski and S. Thoroddsen; from a review by D. Quere)

Sharkskin’s Secrets

Sharks are known as extremely fast and agile swimmers, due in part to the surface of their skin. Sharks are covered in very tiny tooth-shaped scales called denticles which are streamlined in the direction of flow over the shark. If you were to run a hand over a shark’s skin from head to tail, it would feel silky smooth, but rub against the grain and it’s like running your hand on sandpaper. Water encounters a similar resistance, which, according to new research, provides the shark with a passive flow control mechanism, requiring no effort on the part of the shark. When water near the shark’s denticles tries to reverse direction, an early stage in flow separation, the denticles naturally bristle, slowing and trapping the reversed flow. This prevents local flow separation which would otherwise increase the shark’s drag and hinder its agility. (Photo credit: James R. D. Scott; Research by A. Lang et al.)

Boiling Without Bubbles

Water droplets sprinkled on a sufficiently hot frying pan will skitter and skate across the surface on a thin layer of vapor due to the Leidenfrost effect. When a solid object is much warmer than a liquid’s boiling temperature, the surface is surrounded by a vapor cloud until the solid cools to the point that the vapor can no longer be sustained. Then the vapor breaks down in an explosive boiling full of bubbles. Unless, as researchers have just published in Nature, the solid is treated with a superhydrophobic coating. The water-repellent surface prevents the bubbling, even as the sphere cools. The technique could be used to reduce drag in applications like the channels of a microfluidic device. (Video credit: I. Vakarelski et al.; see also Nature News; submitted by Bobby E)

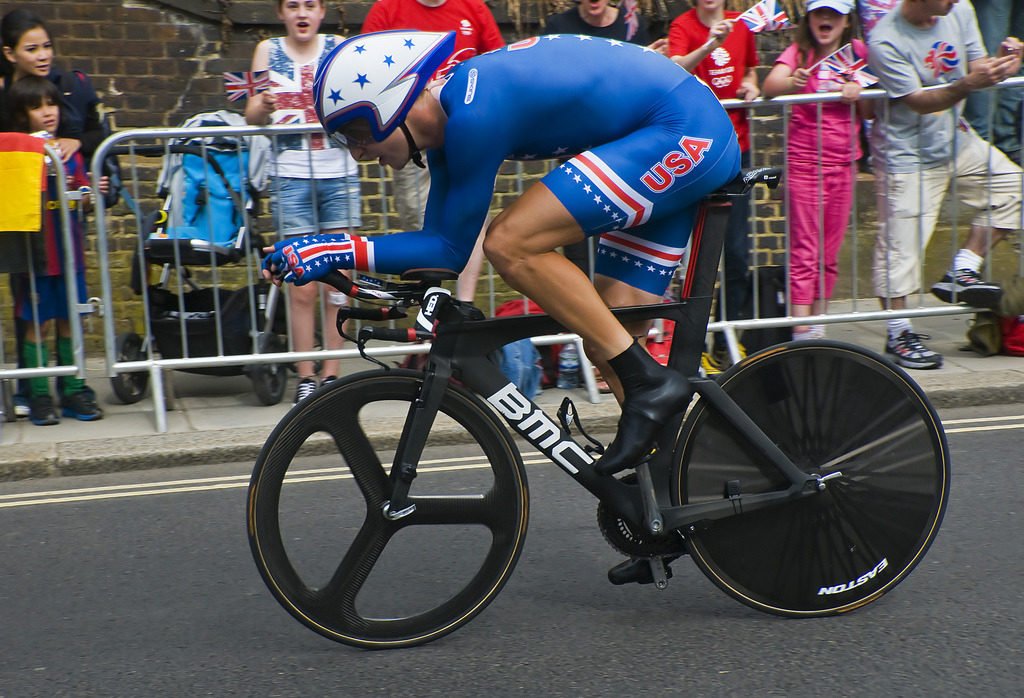

London 2012: Cycling Physics

In no discipline of cycling is more emphasis placed on fluid dynamics than in the individual time trial. This event, a solo race against the clock, leaves riders no place to hide from the aerodynamic drag that makes up 70% or more of the resistance riders overcome when pedaling. Time trial bikes are designed for low drag and light weight over maneuverability, using airfoil-like shapes in the fork and frame to direct airflow around the bike and rider without separation, which creates an area of low pressure in the wake that increases drag. Riders maintain a position stretched out over the front wheel of the bike, with their arms close together. This position reduces the frontal area exposed to the flow, which is proportional to the drag a rider experiences.

Special helmets, some with strangely streamlined curves, are used to direct airflow over the rider’s head and straight along his or her back. Both helmets and skinsuits are starting to feature areas of dimpling or raised texturing. These function in much the same way as a golf ball; the texture causes the boundary layer, the thin layer of air near a surface, to become turbulent. A turbulent boundary layer is less susceptible to separating from the surface, ultimately leading to lower drag than would be observed if the boundary layer remained laminar. Wheels, skinsuits, gloves, shoe covers, and even the location of the brakes on the bike are all tweaked to reduce drag. In an event that can be decided by hundredths of a second between riders, every gram of drag counts. (Photo credits: Stefano Rellandini, POC Sports, Reuters, Paul Starkey, Louis Garneau)

FYFD is celebrating the Olympics by featuring the fluid dynamics of sports. Check out our previous posts on how the Olympic torch works, what makes a pool fast, the aerodynamics of archery, and the science of badminton.

London 2012: Swimming Pool Physics

The era of the LZR suit may be over in swimming, but technology is still making an impact when it comes to making swimmers faster. One thing you’ll often hear from commentators is how the London Aquatic Center boasts one of the world’s fastest pools. When swimmers compete, they have to contend with all the turbulence created in the pool by eight people trying to direct as much water behind them as possible as quickly as possible. Like ripples spreading on a pond, these waves travel, reflect, and interfere, ultimately disrupting the swimmers and causing extra drag. In a fast pool, engineers have made adjustments to reduce the impact of these waves on swimmers. Firstly, the pool is 3 meters deep, meaning that vertical disruptions are mostly damped out before they reach the bottom, so any wave reflected off the bottom of the pool will be extremely weak. Along the sides and ends of the pool, a special trough captures surface waves, preventing them from reflecting back out into the pool. The lane lines are also designed to soak up wave energy so that it does not propagate as much between lanes. When waves hit the lines, their links spin, dissipating some of the wave’s energy.

Despite these advances, the outermost lanes–those against the walls–are not used in competition. This helps to equalize the turbulence between lanes. Whether there is any fluid mechanical advantage to being in a particular lane is debatable. The outer lanes have the advantage of only one competitor’s wake to contend with, but they isolate the swimmer so he or she cannot see their competition as well. In the inner lanes, you’ll sometimes see swimmers try to swim close to the lane line if their competition is ahead of them, the idea being that they may be able to draft on their competitor’s bow wave to reduce drag. Generally speaking, the lane positions are determined by seeding going into the event, where the faster swimmers are given the innermost lanes. This is why it’s rare to see gold medals coming from the outermost lanes. For more, check out NBC’s video on designing fast pools (US only, unfortunately). (Photo credits: Associated Press, Reuters, Geoff Caddick)

Reader Question: Drafting in Cycling

jonesmartinez asks:

As a cyclist, I’m curious about drafting. How fast do I need to be going for there to be a measurable benefit? Additionally, often in a time trial a single rider is often followed by the team car and I’ve heard the rider can be pushed by the air around the team car. Any truth to this rumor? Thanks, I love the blog.

Drafting plays a major role in cycling and its tactics (check out our previous series on cycling). In general, drag increases with the square of velocity and data show this holds for cyclists. The rule of thumb I’ve heard given is that aerodynamic drag doesn’t play a large role below 15 mph, but I have not seen the numbers that inform that claim. Moreover, you have to consider the resultant airspeed around the cyclist. For example, a cyclist moving 13 mph into a 15 mph headwind (28 mph effective) will be experiencing more drag than a cyclist moving 20 mph with a 10 mph tailwind (10 mph effective). With drag being reduced 25-40% by drafting a leading rider, it is almost always beneficial to get behind someone.

That said, I have seen no measurable benefit for a leading rider with a paceline behind him, even though this should, in theory, reduce the drag on the lead rider by closing out his wake. With a large object like a car behind a solo rider, there might theoretically be some benefit. However, the car would have to be driving extremely close to the rider–far closer than they do in reality.

That said, with the prevalence of power meters in the amateur market these days, I think it would be a neat project to go out and try a few of these things firsthand and see whether such tactics actually result in a measurable difference in a cyclist’s performance–though I don’t recommend riding a foot off the front or back of a car!

Supercavitating Penguins

[original media no longer available]

Penguins, already fluid dynamicists by nature, have developed clever methods of increasing their speed to escape from the leopard seals that prey on them. In the clip above, notice from 1:55 onward as the penguins swim for the surface and leap onto the ice – they leave a trail of bubbles in their wake. The penguins are using supercavitation to decrease their drag. When the penguins first dive in to the water, they splay their feathers out in the air and then lock them closed in the water, trapping pockets of air beneath them. When the need for a burst of speed arises, the penguin shifts its feathers to release the air, coating most of its body in a layer of bubbles. Because the drag in air is much less than the drag in water, this enables the bird to achieve much higher speeds than they normally do when swimming.

Flying Squid

Ever seen a squid fly? Not many have, but the behavior may be more common than you think. Thanks to a set of photos from an amateur photographer, scientists have managed to estimate the velocity and acceleration of squid as they propel themselves out of the water by squirting a jet behind them. Researchers found that their speeds in air are roughly five times that in water, thanks to decreased drag. Previously it was thought that the flying behavior might be linked to escaping predators, but some now suggest that it enables migration over long distances by saving energy.

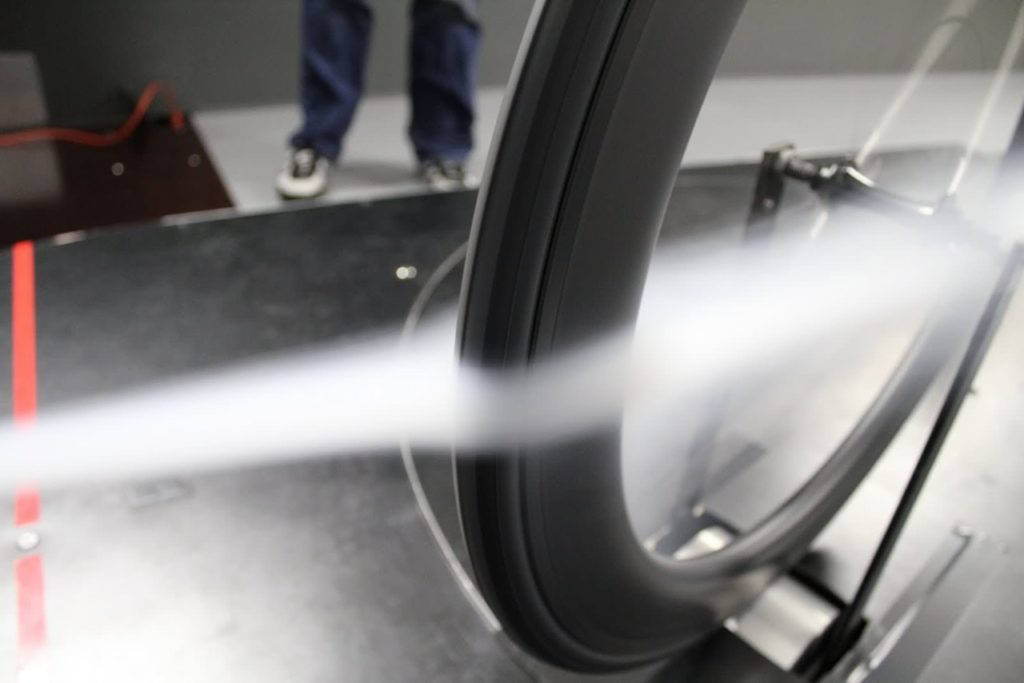

Tour de France Physics: Wind Tunnel Testing

Over hours of racing, even a few grams of drag can be the difference between the top of the podium and missing out. For manufacturers as well as for individual professional cyclists, hours of wind tunnel testing help determine optimum configurations of equipment and positioning. During a day of wind tunnel testing, a cyclist may complete dozens of runs, in which bikes, wheels, helmets, skinsuits, and positioning are all tested and tweaked to find the best combination of aerodynamics.

But wind tunnel results don’t always translate perfectly to the road, where buildings, people, cars and other cyclists may interfere with the freestream. And, as any cyclist will attest, the wind is constantly shifting and changing speeds as one rides. The Garmin-Cervelo pro team has developed a rig to measure wind speeds and angles experienced by cyclists in real world conditions. (The exact components used are unclear, but probably include some form of Pitot tube or 5-hole probe.) As more on-the-road data is collected, wind tunnel tests can be improved by placing greater emphasis on the most common wind angle conditions. (Photo credits: John Cobb, Flo Cycling, and Nico T)

This completes FYFD’s weeklong celebration of the Tour de France and the fluid dynamics of cycling. See previous posts on drafting in the peloton, pacelining and echelons, the art of the sprint lead-out train, and the aerodynamics of time-trialing.