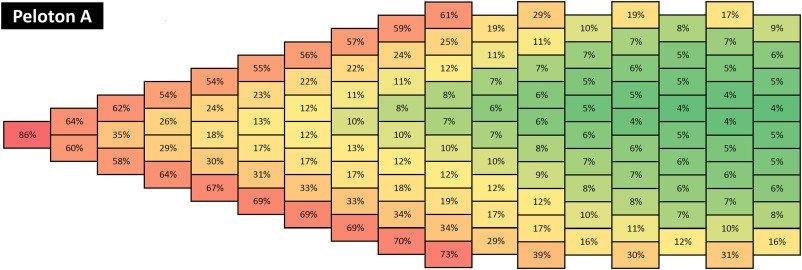

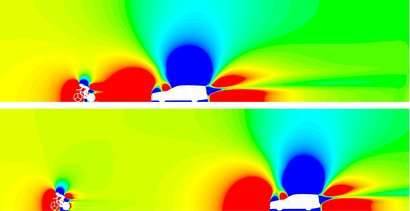

It’s well-known by professional cyclists that sitting in the middle of the peloton requires little effort to overcome aerodynamic drag, but now, for the first time, there’s a scientific study to back that up. Researchers built their own quarter-scale peloton of 121 riders to investigate the aerodynamic effect of cycling in such a large group versus riding solo. Through wind tunnel studies and numerical simulation, they found that riders deep in the peloton can experience as little as 5-10% of the aerodynamic drag of a solo cyclist.

Tactically, this means teams should aim to position their protected leader or sprinter mid-way in the pack, where they’ll receive lots of shelter without risking one of the crashes common near the back of the peloton. It also suggests that teams wanting to isolate another team’s leader should try to push them toward the outer edges of the peloton rather than letting them sit in the middle. It will be interesting to see whether pro teams shift their race strategies at all with these numbers in hand.

Of course, this study considers only a pure headwind. But other groups are looking at the effects of side winds on cyclists. (Image credit: J. Miranda; image and research credit: B. Blocken et al.; submitted by 1307phaezr)