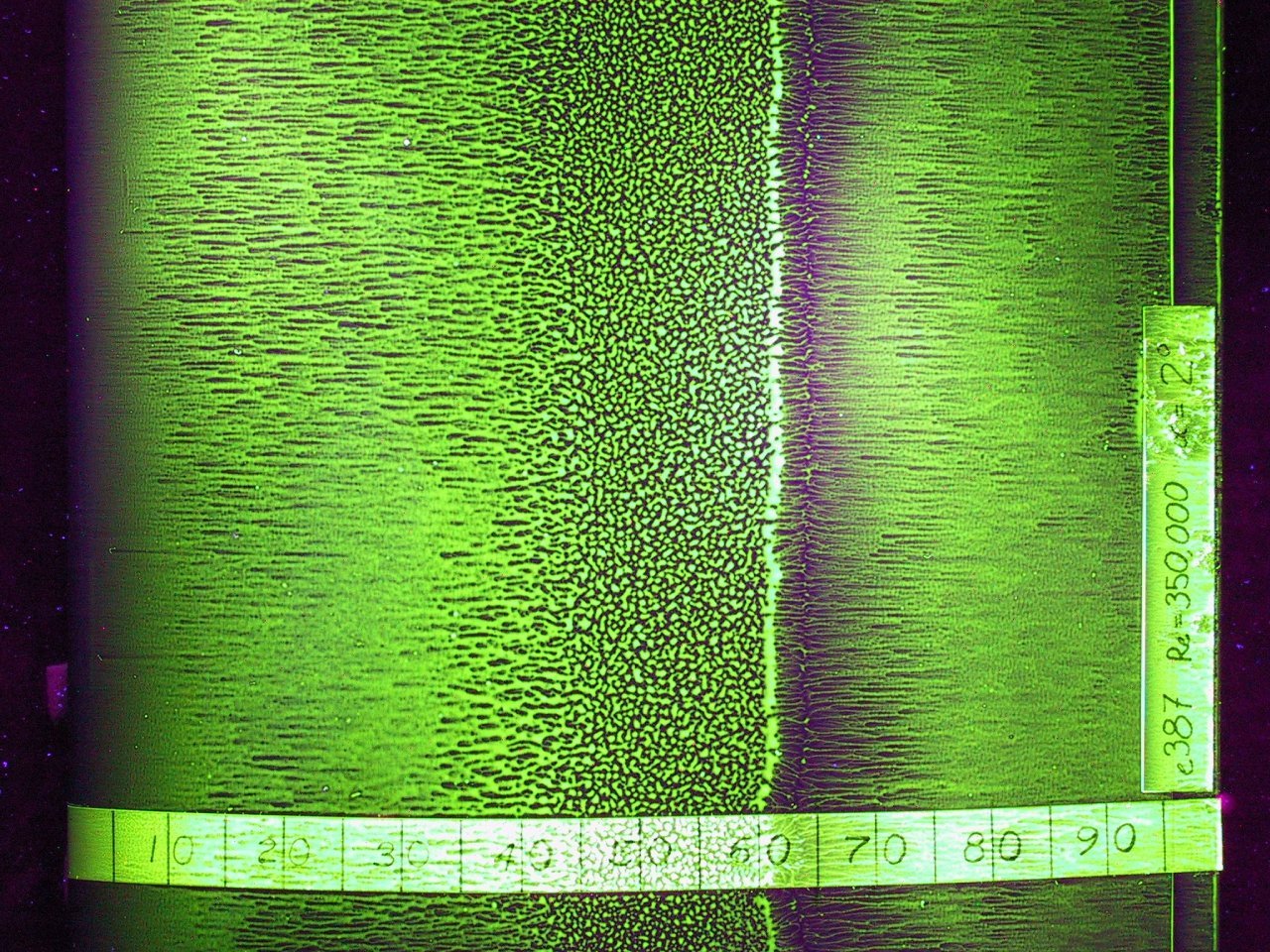

For a long time, people thought baseball aerodynamics were simply a competition between gravity and the Magnus effect caused when a ball is spinning. But the seams of a baseball are so prominent that they, too, have a role to play. Here’s a baseline image of flow around a non-spinning baseball:

As in our previous post on golf, the colors indicate the direction of vorticity but don’t matter much to us here. What’s important is that the wake behind the ball is straight, indicating that there is no additional force beyond gravity and drag acting on the ball. Contrast this to the spinning baseball below:

This ball is spinning in a clockwise motion, which causes flow to separate from the ball earlier on the advancing (bottom) side and later on the retreating (top) side. As a result, the wake is tilted downward. This indicates an upward force on the ball, caused by the Magnus effect.

But what if the seams fall in a place where they affect the flow? Here’s another baseball that’s not spinning:

Notice that seam sitting just past the widest point on the top of the baseball. Flow around that wide point (called the shoulder) is very sensitive to disturbances essentially because the boundary layer is just barely hanging on to the ball. The blue arrow marks where the boundary layer separates from the ball on the top, which takes place earlier than the flow separation on the bottom, marked by the red arrow. As a result, the wake of the ball is tilted upward, indicating a downward force on the ball. The researchers who first proved this effect call it a seam-shifted wake, and it turns out to be a very common effect in baseball. They’ve got a great blog dedicated to baseball aerodynamics where you can learn tons more if you’re interested. (Image credit: top – Pixabay, others – B. Smith; research credit: B. Smith; see also Baseball Aerodynamics)

Today wraps up our Olympic coverage, but if you missed our earlier posts, you can find them all here.