Engineers have been adapting biological materials into robotics in recent years. One of the latest versions of this trend is “necroprinting,” in which researchers built a microscale 3D printer around a mosquito’s proboscis. Made to pierce thick skin to reach blood, the mosquito proboscis offered the kind of size, geometry, and stiffness needed for small-scale printing. The team found that their necroprinter performed well at the ~20 micron scale, with the mosquito-based nozzle costing only a fraction of what a conventional human-made nozzle would. (Image credit: NIAID; research credit: J. Puma et al.; via Ars Technica)

Tag: biology

A Drop of Algae

Spheres of a Volvox colonial algae glow green inside a droplet in this award-winning microphotograph by Jan Rosenboom. Pinned on an inclined surface, the droplet is frozen in a balance between gravity and surface tension that keeps its shape–and its contact angles–asymmetric. Droplets will also take on a shape similar to this when air is blowing past them. (Image credit: J. Rosenboom; via Ars Technica)

Marangoni Effect in Biology

For decades, biologists have focused on genetics as the key determiner for biological processes, but genetic signals alone do not explain every process. Instead, researchers are beginning to see an interplay between genetics and mechanics as key to what goes on in living bodies.

For example, scientists have long tried to unravel how an undifferentiated blob of cells develops a clear head-to-tail axis that then defines the growing organism. Researchers have found that, rather than being guided purely by genetic signals, this stage relies on mechanical forces–specifically, the Marangoni effect.

The image above shows a mouse gastruloid, a bundle of stem cells that mimic embryo growth. As they develop, cells flow up the sides of the gastruloid, with a returning downward flow down the center. This is the same flow that happens in a droplet with higher surface tension in one region; the Marangoni effect pulls fluid from the lower surface tension region to the higher one, with a returning flow that completes the recirculation circuit.

The same thing, it turns out, happens in the gastruloid. Genes in the cells trigger a higher concentration of proteins in one region of the bundle, creating a lower surface tension that causes tissue to flow away, helping define the head-to-tail axis. (Image credit: S. Tlili/CNRS; research credit: S. Gsell et al.; via Wired)

The Best of FYFD 2025

Happy 2026! This will be a big year for me. I’ll be finishing up and turning in the manuscript for my first book — which flows between cutting edge research, scientists’ stories, and the societal impacts of fluid physics. It’s a culmination of 15 years of FYFD, rendered into narrative. I’m so excited to share it with you when it’s published in 2027.

As always, though, we’ll kick off the year with a look back at some of FYFD’s most popular posts of 2025. (You can find previous editions, too, for 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, and 2014.) Without further ado, here they are:

- Charged Drops Don’t Splash

- Strata of Starlings

- Espresso in Slow-Mo

- The Incredible Engineering of the Alhambra

- Uranus Emits More Than Thought1

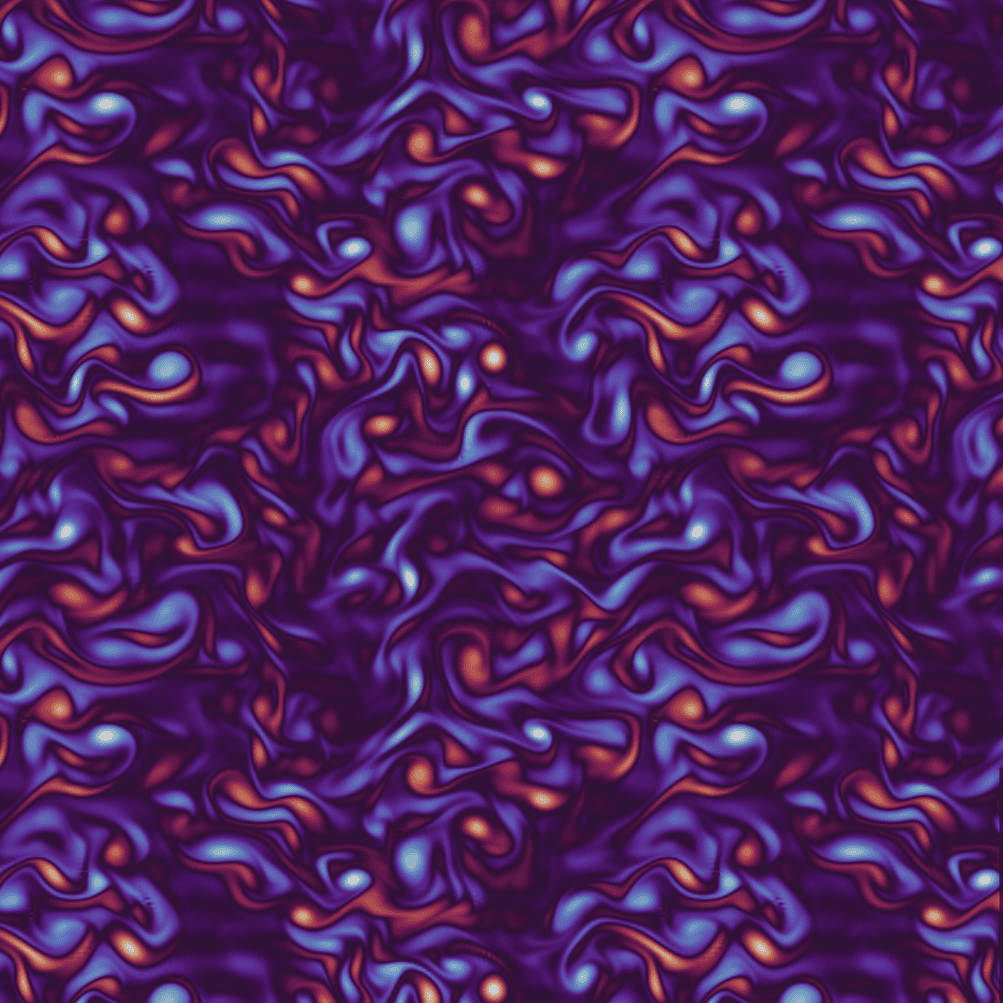

- Kolmogorov Turbulence

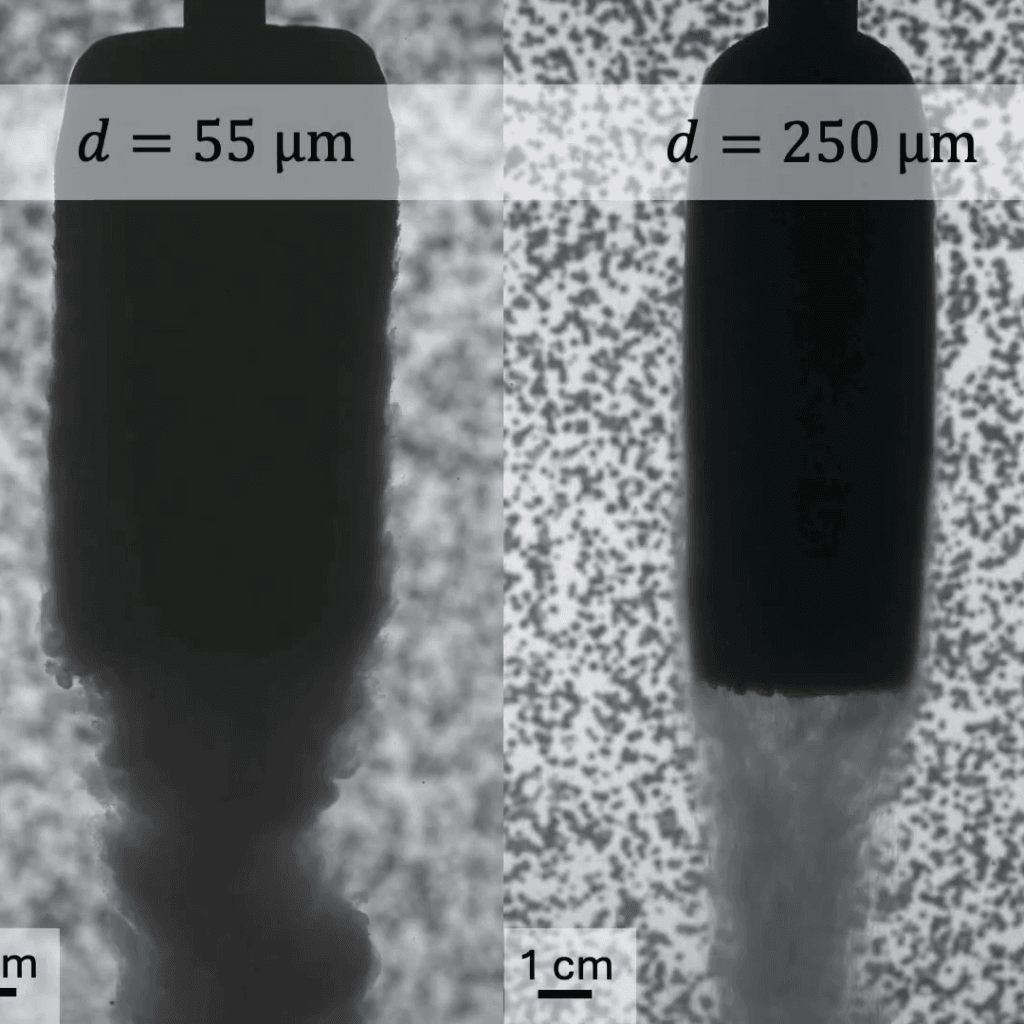

- Bow Shock Instability

- How Particles Affect Melting Ice

- The Puquios System of Nazca

- Cooling Tower Demolition

- A Glimpse of the Solar Wind

- Bubbling Up

- A Sprite From Orbit

- Cornflower Roots Growing

- How Sunflowers Follow the Sun

What a great bunch of topics! I’m especially happy to see so many research and research-adjacent posts were popular. And a couple of history-related posts; I don’t write those too often, but I love them for showing just how wide-ranging fluid physics can be.

Interested in keeping up with FYFD in 2026? There are lots of ways to follow along so that you don’t miss a post.

And if you enjoy FYFD, please remember that it’s a reader-supported website. I don’t run ads, and it’s been years since my last sponsored post. You can help support the site by becoming a patron, buying some merch, or simply by sharing on social media. And if you find yourself struggling to remember to check the website, remember you can get FYFD in your inbox every two weeks with our newsletter. Happy New Year!

(Image credits: droplet – F. Yu et al., starlings – K. Cooper, espresso – YouTube/skunkay, fountain – Primal Space, Uranus – NASA, turbulence – C. Amores and M. Graham, capsule – A. Álvarez and A. Lozano-Duran, melting ice – S. Bootsma et al., puquios – Wikimedia, cooling towers – BBC, solar wind – NASA/APL/NRL, Lake Baikal – K. Makeeva, sprite – NASA, roots – W. van Egmond, sunflowers – Deep Look)

- I know what I did. ↩︎

Lung Flows

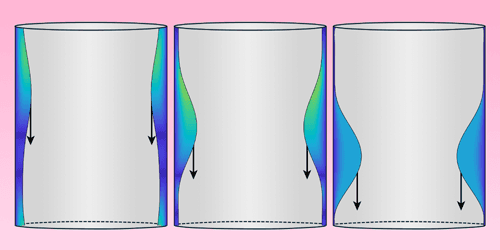

When a fluid coats the inner walls of a cylinder, it can move downward in what’s called a collar flow. In our airways, a sinking collar flow can thicken as it falls, eventually blocking the airway completely.

In a Newtonian fluid, this thickening during motion is essentially unavoidable; any small disturbance to the fluid will make its thickness change. But in a viscoplastic fluid–one more akin to the mucus in our airways–researchers found that, below a critical film thickness, the collar flow won’t thicken to form a blockage. (Image and research credit: J. Shemilt et al.; via APS)

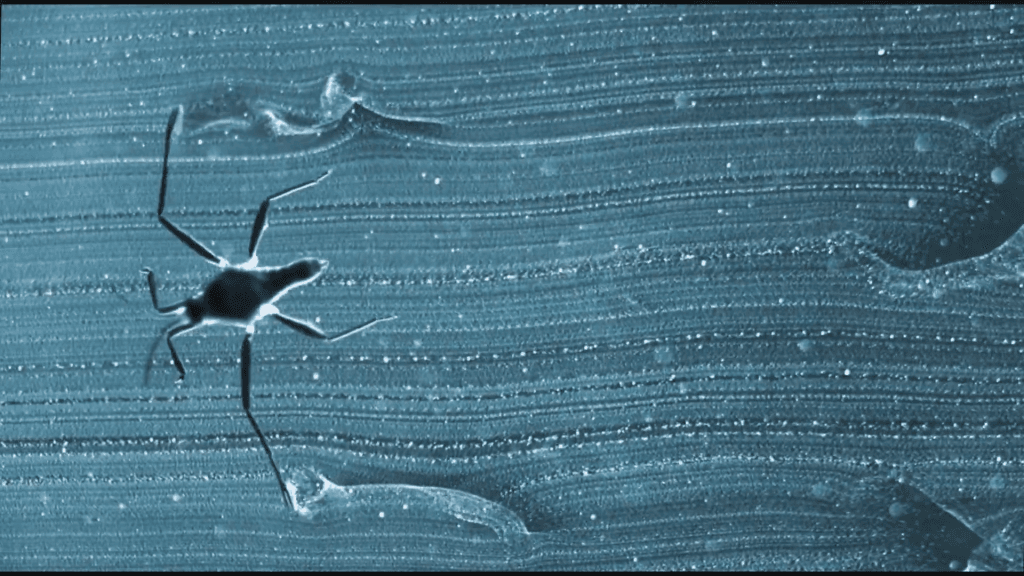

Ripple Bugs

Ripple bugs are a type of water strider capable of moving at a blazing fast 120 body lengths per second across the water surface. In addition to their speed, ripple bugs are incredibly agile and are active almost constantly. Researchers believe they’ve found the insect’s secret: feather-like hydrophilic fans that spread on contact with the water. These fans help the insects push off the water and steer, but they require no effort to open and close. They’ve even adapted the technique to bio-inspired robots and seen improvements in speed, agility, and efficiency. (Video credit: Science; research credit: V. Ortega-Jimenez et al.)

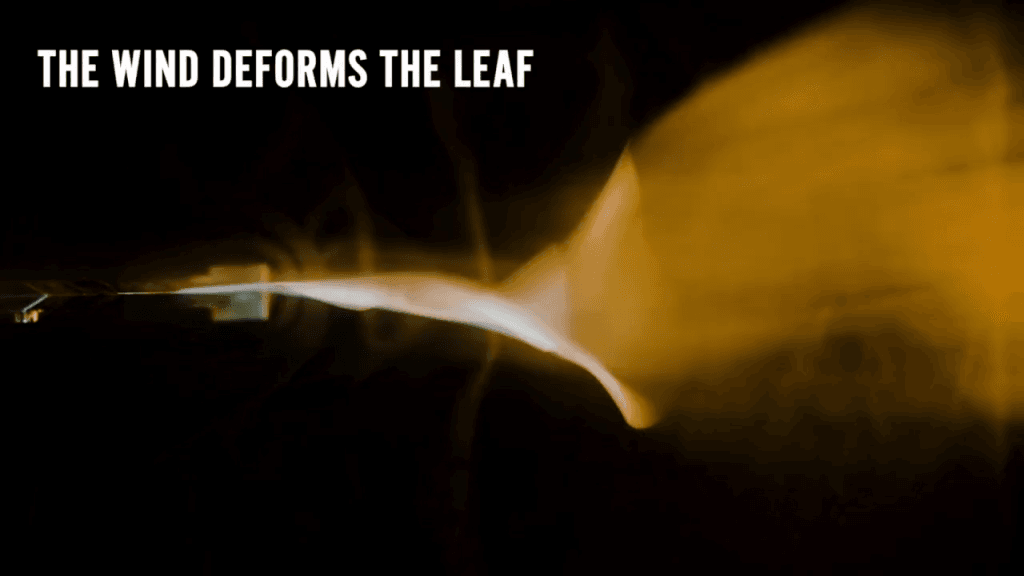

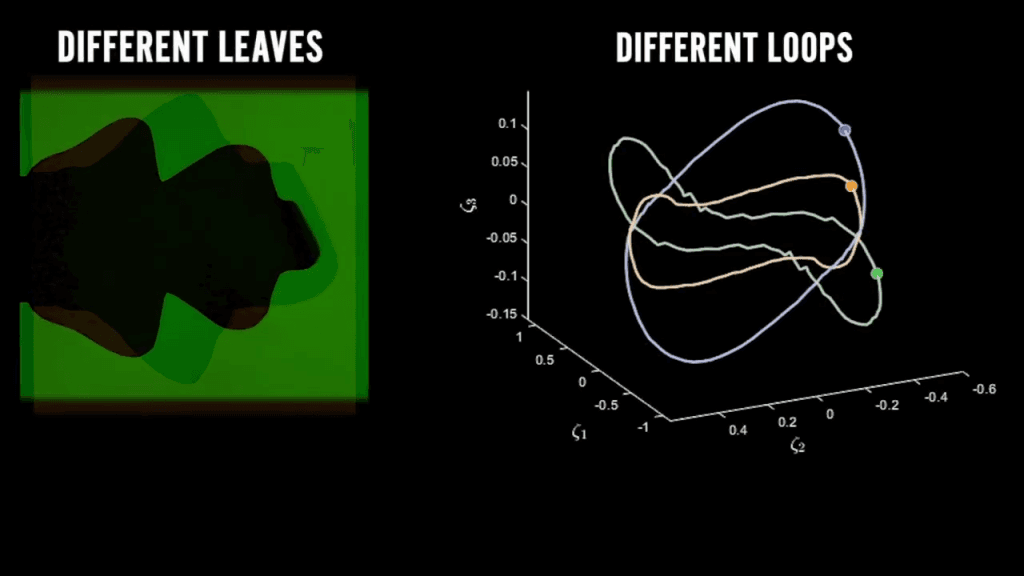

Leaves Dance in the Wind

Once a breeze kicks up, leaves on a tree start dancing. Every tree’s leaves have their own shapes, some of which appear very different from other trees. But their dances have patterns, as this video shows. In it, researchers explore how leaves of different shapes deform in the wind and how they can decompose that motion to compare across leaves. (Video and image credit: K. Mulleners et al.; via GFM)

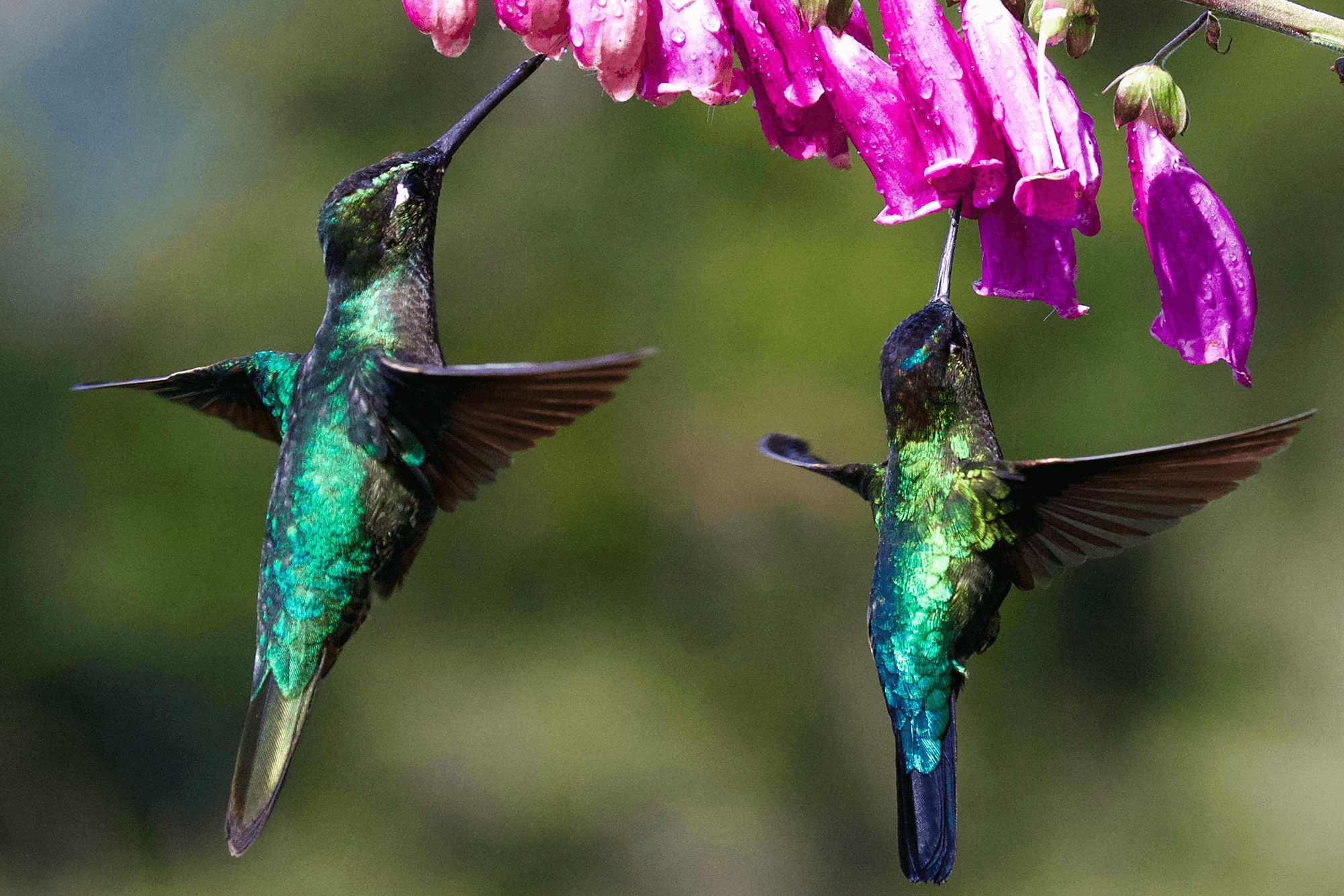

Controlling Hovering

Hummingbirds and many insects hover when feeding, escaping predators, and mating. While scientists have decoded the mechanics of a hummingbird’s figure-8-like hovering wingstroke, it’s been harder to understand how the creatures control their hovering. Most of our attempts to control hovering require more computational power than hummingbirds and insects are thought to have. But this study describes a new control scheme: one that allows stable, real-time hovering with little computational cost. (Image credit: J. Wainscoat; research credit: A. Elgohary and S. Eisa; via APS)

In Deep Lakes, Mixing is Disappearing

With a depth of nearly 600 meters, Crater Lake in Oregon is the deepest lake in the United States. It’s known for its brilliant blue hue and startling clarity. But, like other deep lakes, Crater Lake is changing as temperatures warm. It’s edging ever closer to a day where its deep, cold waters no longer mix.

Although the details of mixing vary from lake to lake, older records show that most deep lakes would overturn and fully mix on a frequency that ranged from twice a year to every seven years. This overturning happens when winds push frigid, near-frozen water. As that water approaches the shoreline, it gets forced downward, where the pressure at depth makes the cold water denser still, causing it to sink beneath the warmer water layer near the lake bottom. That kicks off larger-scale mixing that redistributes oxygen, nutrients, and toxins in the lake.

When this regular mixing stops, the entire ecosystem gets affected. Over time, oxygen gets depleted in deeper in the lake, leaving a dead zone unable to support fish and other aquatic life. Meanwhile, longer and warmer growing seasons favor phytoplankton and algae that cloud the waters and disrupt a lake’s unique ecology.

For a much more detailed look at deep lake mixing and the changes we’re seeing, check out this article over at Quanta Magazine. It’s a longer read but well worth your time. (Image credit: N. Perez Aguilar; see also: Quanta Magazine)

Deep Breaths Renew Lung Surfactants + A Special Announcement

Taking a deep breath may actually help you breathe easier, according to a new study. When we inhale, air fills our alveoli–tiny balloon-like compartments within our lungs. To make alveoli easier to open, they’re coated in a surfactant chemical produced by our lungs. Just as soap’s surfactant molecules squeezing between water molecules lowers the interface’s surface tension, our lung surfactants gather at the interface and lower the surface tension, making alveoli easier to inflate.

But things are a little more complicated in our lungs than in our kitchen sink because of our constant cycle of breathing, which stretches and compresses our lungs’ surfaces and surfactant layers. Imagine a flat interface, lined with surfactant molecules; then stretch it. As the interface stretches, gaps open between the surfactant molecules and allowing molecules from the interior of the liquid to push their way to the newly stretched interface, changing the surface tension. If the interface gets compressed, some of the excess molecules will get pushed back into the liquid bulk.

In looking at how lung surfactants respond to these cycles of compression and stretching, the researchers found that the lung liquid develops a microstructure during cycles of shallow breathing that makes the surface tension higher, thus making lungs harder to fill. In contrast, a deep breath like a sigh replenished the saturated lipids at the interface, lowering surface tension and making lungs more compliant. So a deep sigh actually can help you breathe easier. (Image credit: F. Møller; research credit: M.. Novaes-Silva et al.; via Gizmodo)

P.S. — I’ve got a book (chapter)! Several years ago, I joined an amazing group of women to write two books (one for middle grades and one for older audiences) about our journeys as scientists. And they are out now! In fact, today we’re holding a “Book Bomb” where we aim for as many of us as possible to buy the book(s) on the same day. If you’d like to join (and get ahead on your gift shopping), here are (affiliate) links:

- Persevere, Survive, and Thrive (including my story of becoming a science communicator): Amazon, Bookshop.org

- For All the Curious Girls: Amazon, Bookshop.org