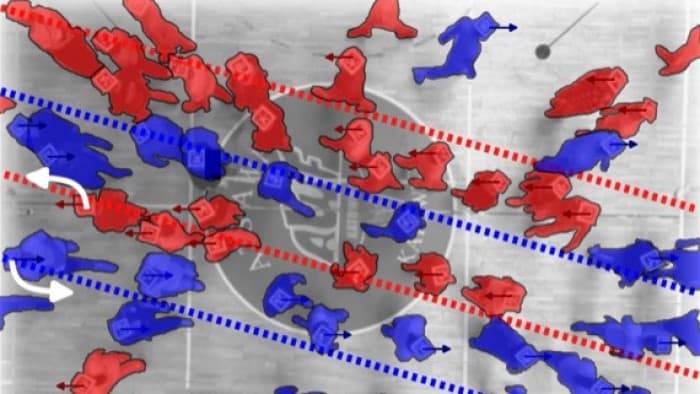

The Feast of San Fermín in Pamplona, Spain draws crowds of thousands. Scientists recently published an analysis of the crowd motion in these dense gatherings. The team filmed the crowds at the festival from balconies overlooking the plaza in 2019, 2022, 2023, and 2024. Analyzing the footage, they discovered that at crowd densities above 4 people per square meter, the crowd begins to move in almost imperceptible eddies. In the animation below, lines trace out the path followed by single individuals in the crowd, showing the underlying “vortex.” At the plaza’s highest density — 9 people per square meter — one rotation of the vortex took about 18 seconds.

The team found similar patterns in footage of the crowd at the 2010 Love Parade disaster, in which 21 people died. These patterns aren’t themselves an indicator of an unsafe crowd — none of the studied Pamplona crowds had a problem — but understanding the underlying dynamics should help planners recognize and prevent dangerous crowd behaviors before the start of a stampede. (Image credit: still – San Fermín, animation – Bartolo Lab; research credit: F. Gu et al.; via Nature)