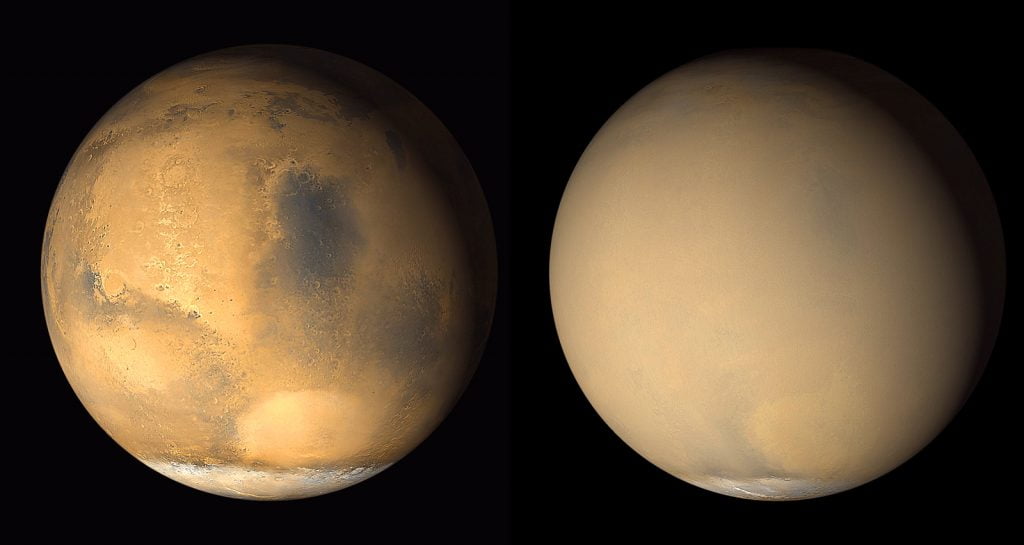

To support a crew on Mars, a landing site must offer resources like water and allow for sufficient power generation. Thus far, most analyses of this sort have focused on the possibilities of solar power, which is limited by day-and-night cycles and seasonal variations, and nuclear power, which carries some risk to the human crew. In a new report, researchers considered the possibilities of wind power on Mars.

Since Mars’s atmosphere is so much thinner than Earth’s, wind power has largely been overlooked as an energy source there. But researchers found that a commercially-rated wind turbine expected to produce 330 kW here on Earth could still output a respectable 10 kW on Mars. Since the target power needs for a crew are 24 kW, adding wind energy can boost a power system from providing 40% of needs from solar alone to 60-90% of the needed energy from combined solar and wind sources. A wind turbine is especially helpful in supplementing power needs at times when solar power wanes, like at night or during the Martian winter solstice. (Image credit: NASA; research credit: V. Hartwick et al.; via Physics World)