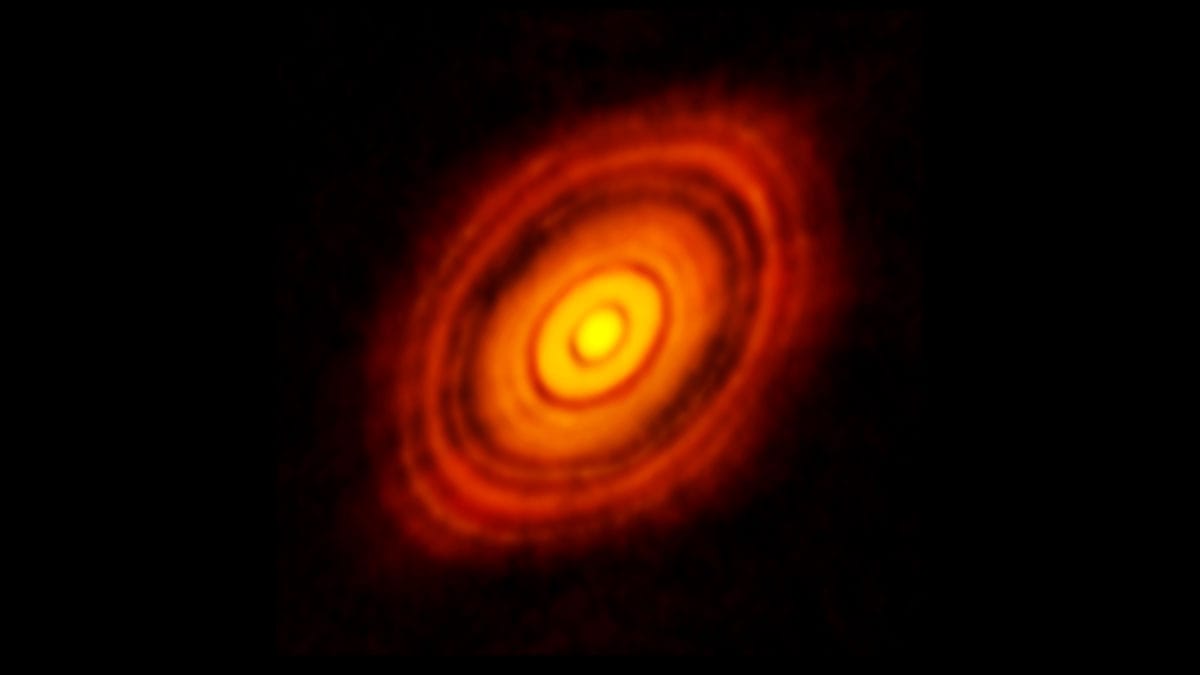

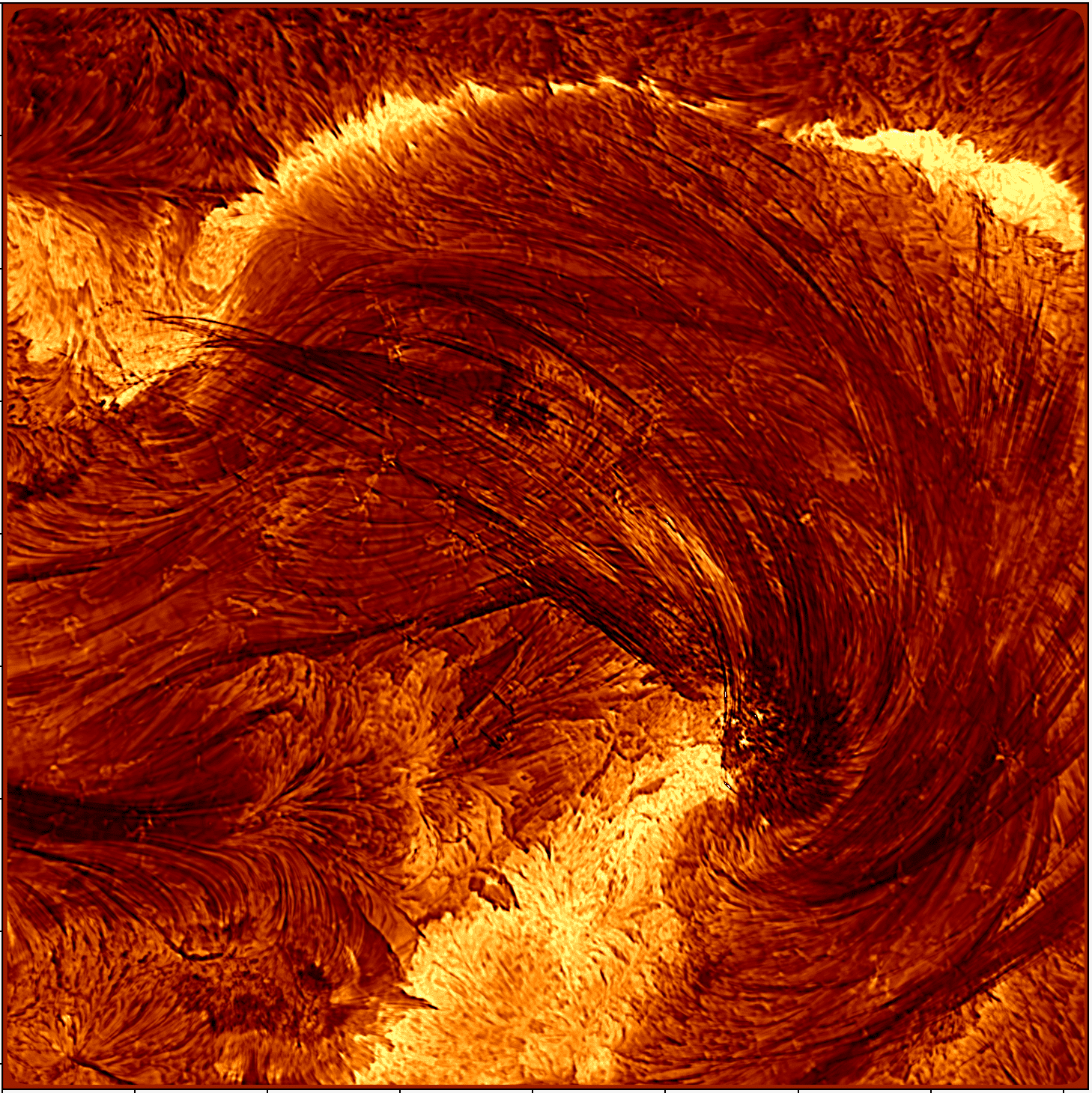

Taking a deep breath may actually help you breathe easier, according to a new study. When we inhale, air fills our alveoli–tiny balloon-like compartments within our lungs. To make alveoli easier to open, they’re coated in a surfactant chemical produced by our lungs. Just as soap’s surfactant molecules squeezing between water molecules lowers the interface’s surface tension, our lung surfactants gather at the interface and lower the surface tension, making alveoli easier to inflate.

But things are a little more complicated in our lungs than in our kitchen sink because of our constant cycle of breathing, which stretches and compresses our lungs’ surfaces and surfactant layers. Imagine a flat interface, lined with surfactant molecules; then stretch it. As the interface stretches, gaps open between the surfactant molecules and allowing molecules from the interior of the liquid to push their way to the newly stretched interface, changing the surface tension. If the interface gets compressed, some of the excess molecules will get pushed back into the liquid bulk.

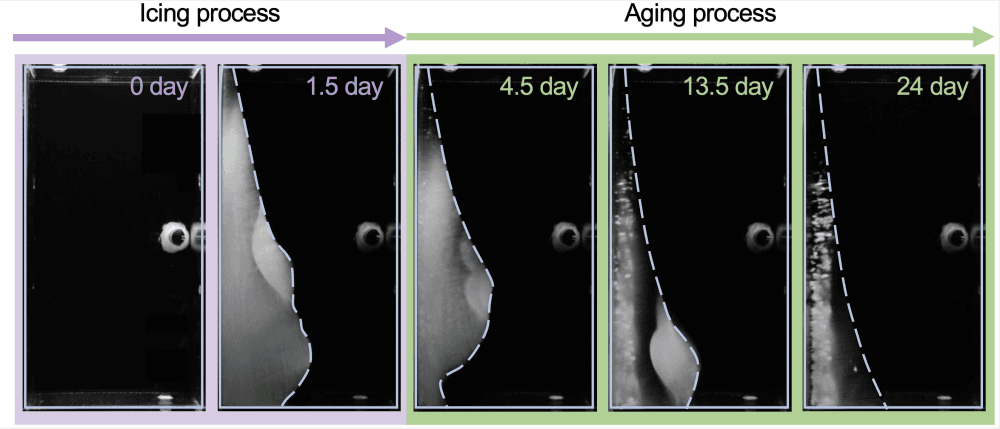

In looking at how lung surfactants respond to these cycles of compression and stretching, the researchers found that the lung liquid develops a microstructure during cycles of shallow breathing that makes the surface tension higher, thus making lungs harder to fill. In contrast, a deep breath like a sigh replenished the saturated lipids at the interface, lowering surface tension and making lungs more compliant. So a deep sigh actually can help you breathe easier. (Image credit: F. Møller; research credit: M.. Novaes-Silva et al.; via Gizmodo)

P.S. — I’ve got a book (chapter)! Several years ago, I joined an amazing group of women to write two books (one for middle grades and one for older audiences) about our journeys as scientists. And they are out now! In fact, today we’re holding a “Book Bomb” where we aim for as many of us as possible to buy the book(s) on the same day. If you’d like to join (and get ahead on your gift shopping), here are (affiliate) links:

- Persevere, Survive, and Thrive (including my story of becoming a science communicator): Amazon, Bookshop.org

- For All the Curious Girls: Amazon, Bookshop.org