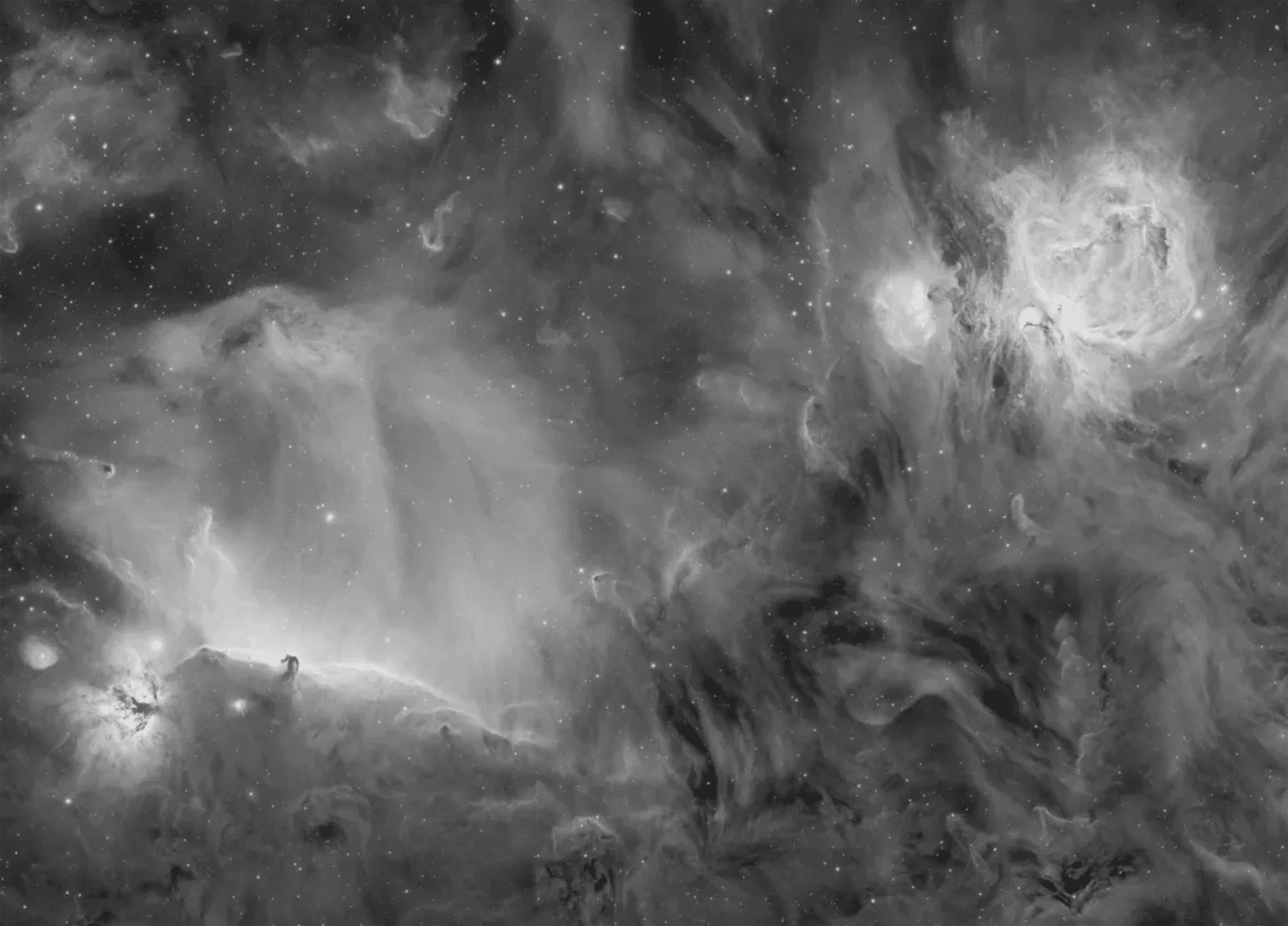

Type 1a supernovae are agreed to be explosions of white dwarf stars, the remains of stars similar in mass to our Sun. They’re thought to be triggered when extra mass — from a nearby companion star, for example — triggers a runaway fusion reaction in their carbon and oxygen, elements that white dwarfs generally don’t have enough mass to successfully fuse. The runaway fusion then blows the star apart.

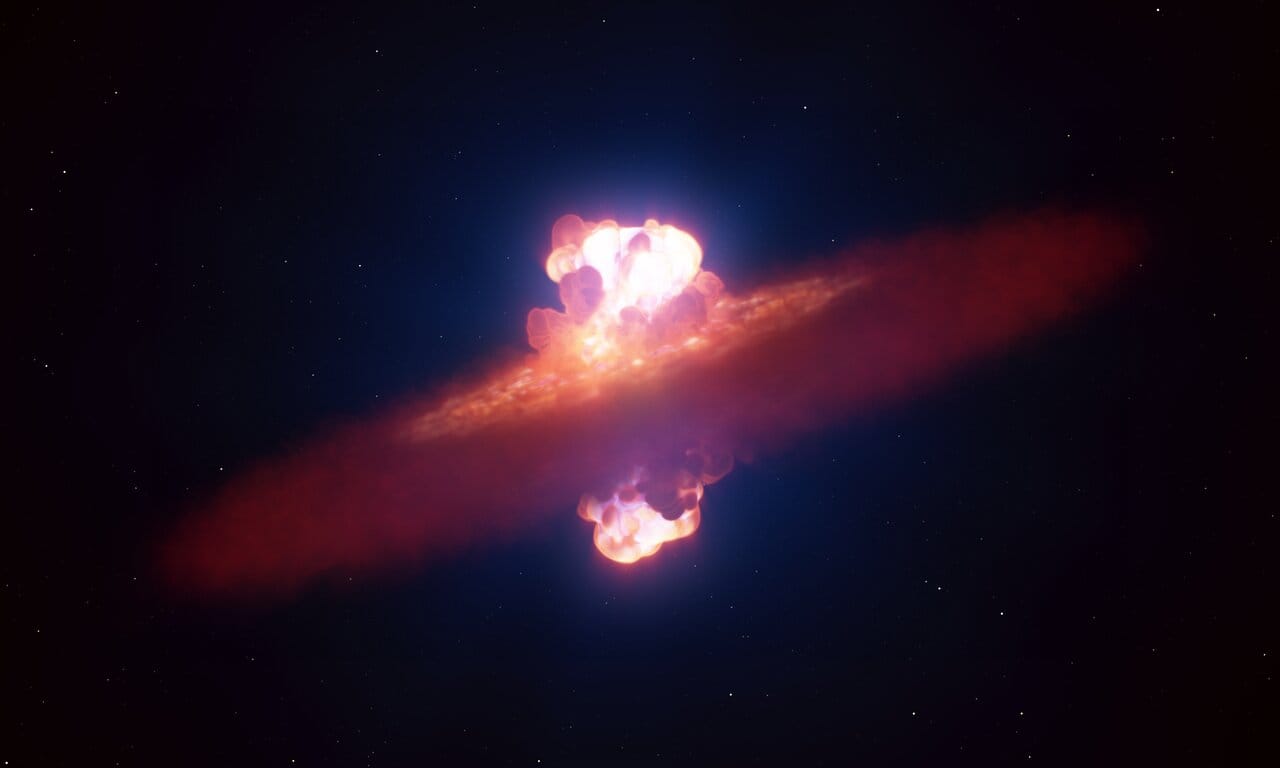

But there’s another theory — demonstrated through numerical simulations — that suggests an alternate mechanism: a small explosion on the star’s surface could compress the interior enough to trigger fusion of the heavier elements there, thereby triggering a second detonation. The two explosions would happen in quick succession, making them difficult to detect, but astronomers predicted that each explosion could create a shell of calcium; given enough time, those two shells could drift apart, allowing astronomers to see a shell of sulfur between them.

The team looked to a supernova remnant about 300 years old, and using a spectrograph from the Very Large Telescope, they were able to image — as predicted — a two shells of calcium, separated by sulfur, supporting the double-detonation hypothesis.

The impact of double-detonation in Type 1a supernovae could be far-reaching. Right now, the intensity of these objects seems to be consistent enough that astronomers use their brightness to estimate their distance. Over the years, those distance estimates have been used to measure the universe’s expansion and provide evidence for the existence of dark matter. But if Type 1a supernovae are not all the same intensity, we may need to reevaluate their use as a universal yardstick. (Image credit: ESO/P. Das et al.; research credit: P. Das et al.; via Ars Technica)