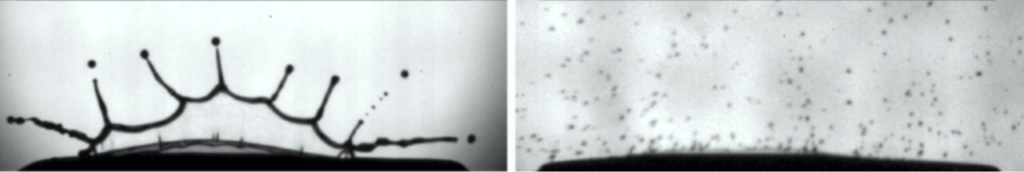

When bubbles burst, they spray a myriad of tiny droplets into the air. In general, the older a bubble gets, the thinner it is, thanks to gravity draining its liquid away. When older bubbles burst, they create tinier and more numerous droplets (upper right) compared to a younger bubble (upper left). But there are more forces than just gravity at play.

Bubbles also undergo evaporation – most effectively at the apex. Evaporation cools the cap of the bubble, increasing its surface tension and triggering a Marangoni flow that helps restore fluid to the bubble film. This stabilizes an aging bubble.

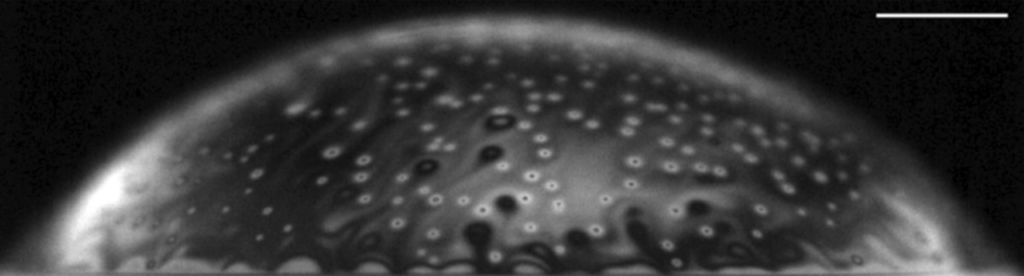

Contamination plays a role as well. The bright spots in the bottom image reveal bacteria in the bubble’s cap. Compared to a clean bubble, these contaminated ones can survive far longer and, when burst, produce 10 times as many droplets as a clean bubble of the same age. That has major implications for disease transmission, especially for bacteria that spend a significant portion of their life cycle in liquids. (Image and research credit: S. Poulain and L. Bourouiba; see also Physics Today)

Leave a Reply