One of the challenges in large-scale wind energy is that operating wind turbines do not behave exactly as predicted by simulation or wind tunnel experiments. To determine where our models and small-scale experiments are lacking, it’s useful to make measurements using a full-scale working turbine, but making quantitative measurements in such a large-scale, uncontrolled environment is very difficult. Here researchers have used natural snowfall as seeding particles for flow visualization. The regular gaps in the flow are vortices shed from the tip of the passing turbine blades. With a searchlight illuminating a 36 m x 36 m slice of the flow behind a wind turbine, the engineers performed particle image velocimetry, obtaining velocity measurements in that region that could then be correlated to the wind turbine’s power output. Such in situ measurements will help researchers improve wind turbine performance. (Video credit: J. Hong et al.)

Tag: wingtip vortices

The Physics of a Flying-V

New research using free-flying northern bald ibises shows that during group flights the birds’ positioning and flapping maximize aerodynamic efficiency. In flight, a bird’s wings generate wingtip vortices, just as a fixed-wing aircraft does. These vortices stretch in the bird’s wake, creating upwash in some regions and downwash in others as the bird flaps. According to theory, to maximize efficiency a trailing bird should exploit upwash and avoid downwash by flying at a 45-degree angle to its leading neighbor and matching its flapping frequency. The researchers found that, on average, this was the formation and timing the flock assumed. In situations where the birds were flying one behind the next in a straight line, the birds tended to offset their flapping by half a cycle relative to the bird ahead of them–another efficient configuration according to theory. Researchers don’t yet know how the birds track and match their neighbors; perhaps, like cyclists in a peloton, they learn by experience how to position themselves for efficiency. For more information, see the researchers’ video and paper. (Photo credit: M. Unsold; research credit: S. Portugal; via Ars Technica; submitted by M. Piedallu van Wyk)

Fluids Round-up – 11 August 2013

Time for another fluids round-up! Here are your links:

- Back in January 1919, a five-story-high metal tank full of molasses broke and released a wave of viscous non-Newtonian fluid through Boston’s North End. Scientific American examines the physics of the Great Molasses Flood, including how to swim in molasses. If you can imagine what it’s like to swim in molasses, you’ll know something of the struggle microbes experience to move through any fluid. They also discusses some of the strange ways tiny creatures swim.

- In sandy desert environments, helicopter blades can light up the night with so-called helicopter halos. The effect is similar to what causes sparks from a grinding wheel. Learn more about this Kopp-Etchells effect.

- Check out this ominous footage of a tornadic cell passing through Colorado last week.

- If you want more of a science-y look to your drinkware, you should check out the Periodic TableWare collection over on Kickstarter.

- Finally, wingsuits really take the idea of gliding flight to some crazy extremes. Check out this video of in-flight footage. Watch for the guy’s wingtip vortices at 3:16 (screencap above)! (submitted by Jason C)

(Photo credit: Squirrel)

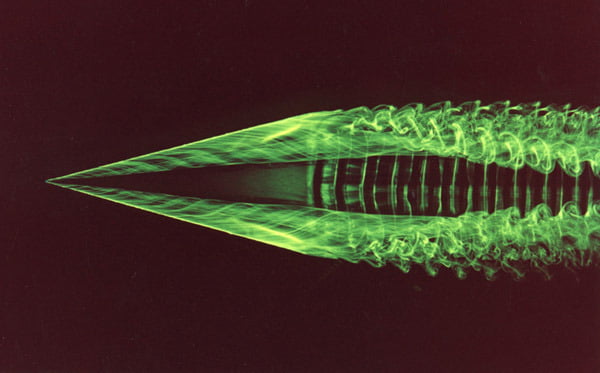

Flow Over a Delta Wing

Fluorescent dye illuminated by laser light shows the formation and structure of vortices on a delta wing. A vortex rolls up along each leading edge, helping to generate lift on the triangular wing. As the vortices leave the wing, their structure becomes even more complicated, full of lacy wisps of vorticity that interact. Note how, by the right side of the photo, the vortices are beginning to draw closer together. This is an early part of the large-wavelength Crow instability. Much further downstream, the two vortices will reconnect and break down into a series of large rings. (Photo credit: G. Miller and C. Williamson)

Wake Vortices at Night

The ends of an airplane’s wings generate vortices that stretch back in the wake of the plane. Most of the time these vortices are invisible, even if their effects on lift are distinctive. Here an A-340 coming in for a foggy landing demonstrates the size and strength of these vortices. Notice how the fog gets swept up and away by the vortices. Pilots will sometimes use this effect to their advantage in clearing a runway of fog by making repeated low-passes to clear the fog before landing. (Video credit: A. Ruesch; submitted by Jens F.)

Those Funny Fins on Airplane Wings

Ever look out an airplane’s window and wondered why a row of little fins runs along the upper side of the wing? These vortex generators help prevent a wing from stalling at high angle of attack by keeping flow attached to the surface. Airflow over the vanes creates a tip vortex that transports the higher-momentum fluid from the freestream closer to the wing’s surface, increasing the momentum in the boundary layer. As a result of this momentum exchange, the boundary layer remains attached over a greater chordwise distance. This also increases the effectiveness of trailing-edge control surfaces, like ailerons, on the wing. (Photo credit: Mark Jones Jr.)

Vapor Cone

This stunning National Geographic photo contest winner shows an F-15 banking at an airshow and a array of great fluid dynamics. A vapor cloud has formed over the wings of the plane due to the acceleration of air over the top of the plane. The acceleration has dropped the local pressure enough that the moisture of the air condenses. Some of this condensation has been caught by the wingtip vortices, highlighting those as well. Finally, the twin exhausts have a wake full of shock diamonds, formed by a series of shock waves and expansion fans that adjust the exhaust’s pressure to match that of the ambient atmosphere. (Photo credit: Darryl Skinner/National Geographic; via In Focus; submitted by jshoer)

Wingtip Vortices

Any finite length wing produces wingtip vortices–potentially intense regions of rotational flow downstream of the wing’s ends. These vortices are associated both with the production of lift on the wing and with unavoidable induced drag. The tabletop demonstration above shows the region of the vortices’ influence and how strong the rotation is there. Note also that the two vortices have opposite rotational senses–the left side induces a clockwise rotation, whereas the right side induces an anti-clockwise rotation. The larger an aircraft, the stronger and longer lasting its vortices; this can be a source of danger for smaller aircraft passing through the wake. If a pilot crosses one wingtip vortex and overreacts to compensate, crossing the second counter-rotating vortex can cause even greater damage.

Sunset Vortices

Wingtip vortices roll up in the wake of this U.S. Coast Guard C-130J. At the edge of a wing high-pressure, low velocity air is able to creep around the edge of the wingtip toward the low-pressure, high-velocity air atop the wing. This creates a swirling vortex that trails behind each wing, made visible here by the clouds entrained in the plane’s wake. Over time, these counter-rotating vortices will sink downward and break up due to viscosity and instabilities induced by their proximity. (via Aviationist)

Helicopter Vortices

When conditions are just right, the low pressure at the center of a wingtip vortex can drop the local temperature below the dew point, causing condensation to form. Here vortices are visible extending from the tips of the propellers in addition to the wingtip. Because of the spinning of the propeller and the forward motion of the airplane, the prop vortices extend backwards in a twisted spiral that will quickly break down into turbulence. The same behavior can be observed with helicopter blades. (Photo credit: benurs)