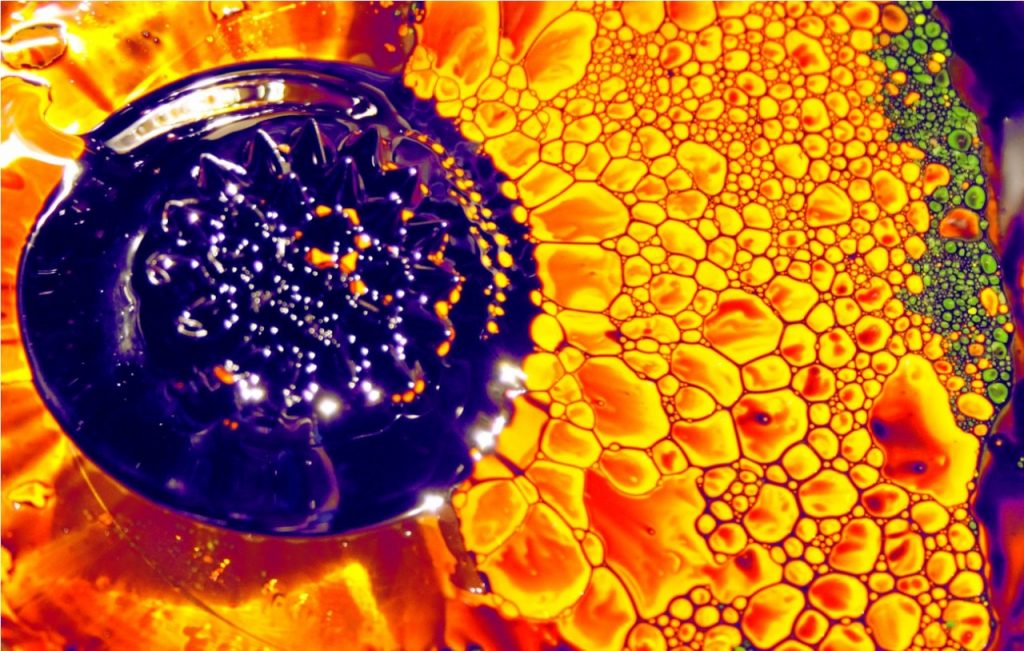

Oobleck is a decidedly weird substance. Made from a dense suspension of cornstarch in water, oobleck is known for its mix of liquid-like and solid-like properties, depending on the force that’s applied. In a recent study, researchers took a look at what happens when you really push oobleck to the extreme. When the force applied to oobleck is small or slowly added, the water between cornstarch particles helps keep the particles apart and free of contact. It’s when the force is large that those particles start jamming up against each other and having friction between them, and then the oobleck suddenly acts like a solid. But what happens once that force is removed?

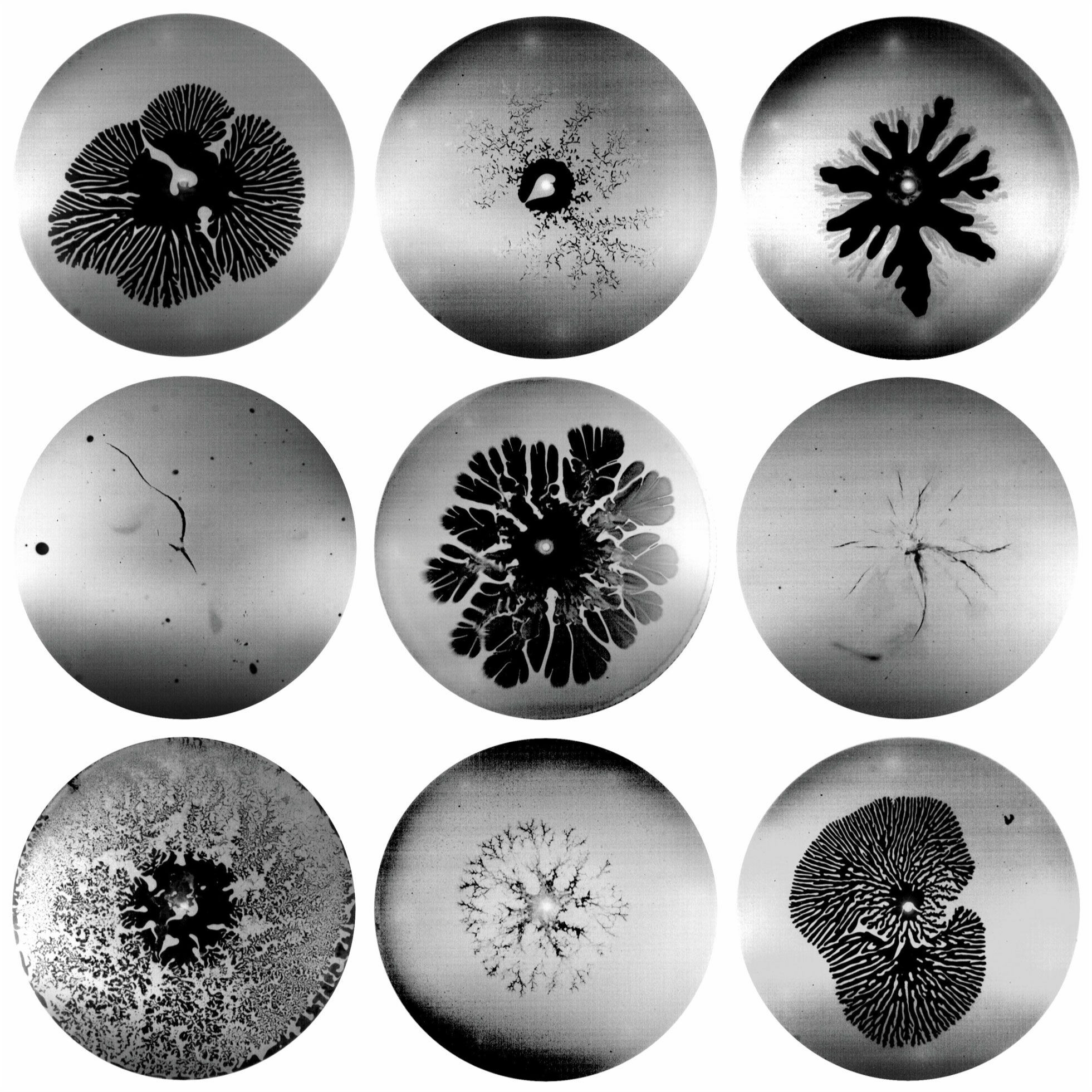

When the force is gone, we expect the particles to repel and for water to squeeze back into the spaces between them, breaking up the friction and allowing the oobleck to relax back to a liquid-like form. But the team found that sometimes the oobleck doesn’t relax as easily as expected; instead, it seems to retain some memory of its solid-like state, due to persisting friction between particles. (Image credit: T. Cox; research credit: J. Cho et al.)