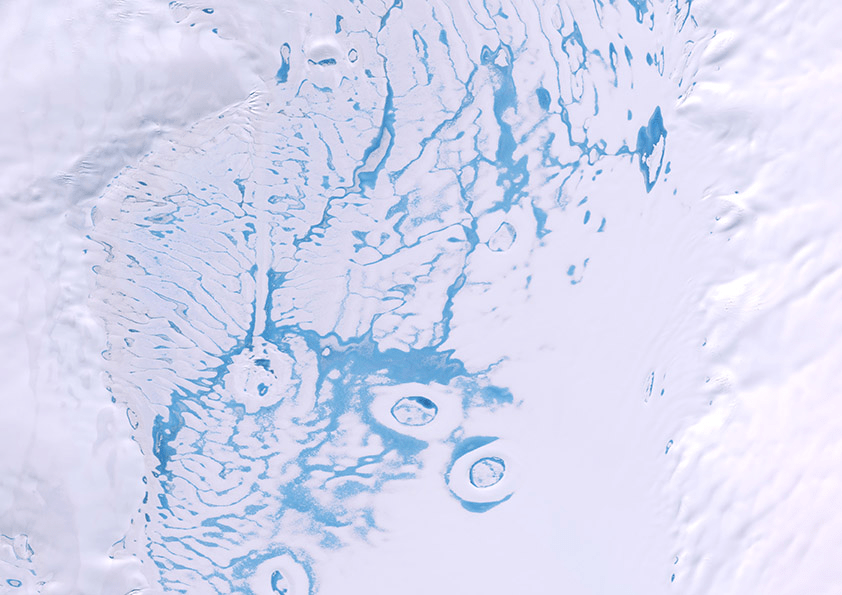

To understand why some sea ice melts and other sea ice survives, researchers tracked millions of floes over decades. This herculean undertaking combined satellite data, weather reports, and buoy data into a database covering nearly 20 years of data. With all of that information, the team could track the changes to specific pieces of ice rather than lumping data into overall averages.

They found that an ice floe’s fate depended strongly on the route it took: ice that slipped from its starting region into warmer, more southern regions was likely to melt. They also saw region-specific effects, like that thick sea ice was more likely to melt in the East Siberian Sea’s summer, possibly due to warmer currents. The comprehensive, fine-grained analyses possible with this ice-tracking technique offer a chance to understand why some Arctic regions are more vulnerable to warming than others. (Image credit: D. Cantelli; research credit: P. Taylor et al.; via Eos)