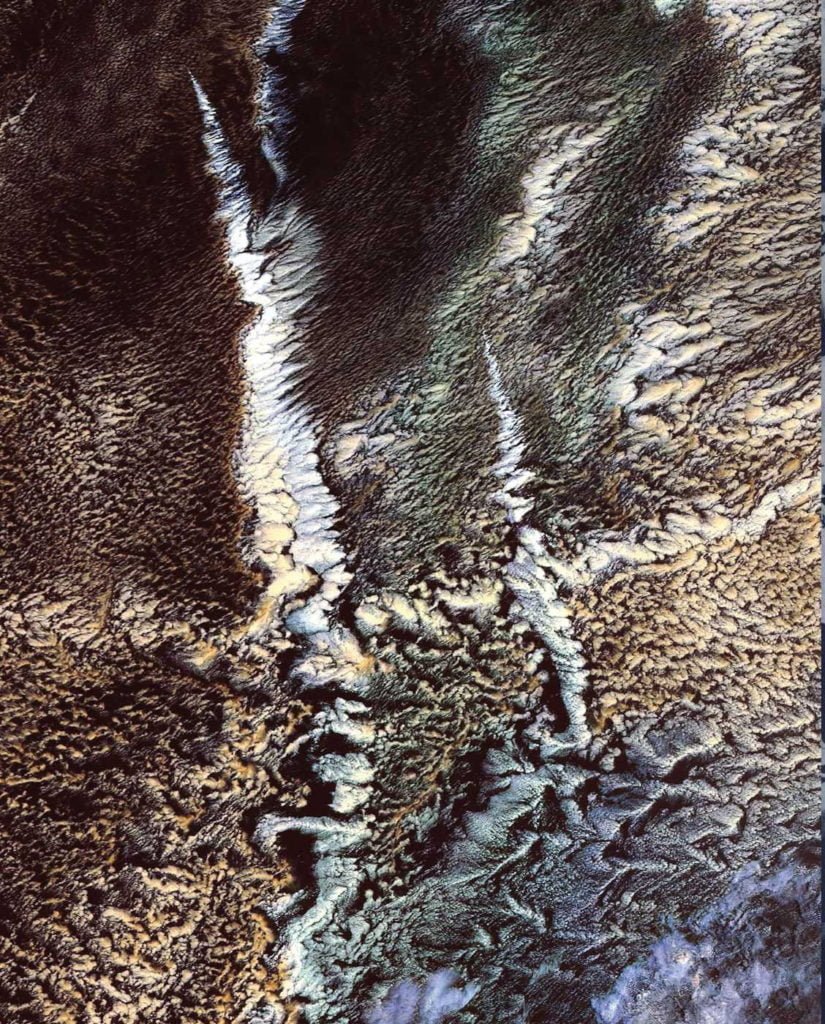

Over the millennia, the Colorado River has carved some of the deepest and most dramatic canyons on our planet. This astronaut photo shows the river near its dam at Lake Powell. The strip of white edging the lake is the “bathtub ring” that shows how the water level has varied over the years. The deep canyons — over 400 meters from the Horn in the center of the photo to the river beside it — throw shadows across the landscape. To reach these depths, the Colorado River incised its path into bedrock that was tectonically uplifted. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Tag: meander

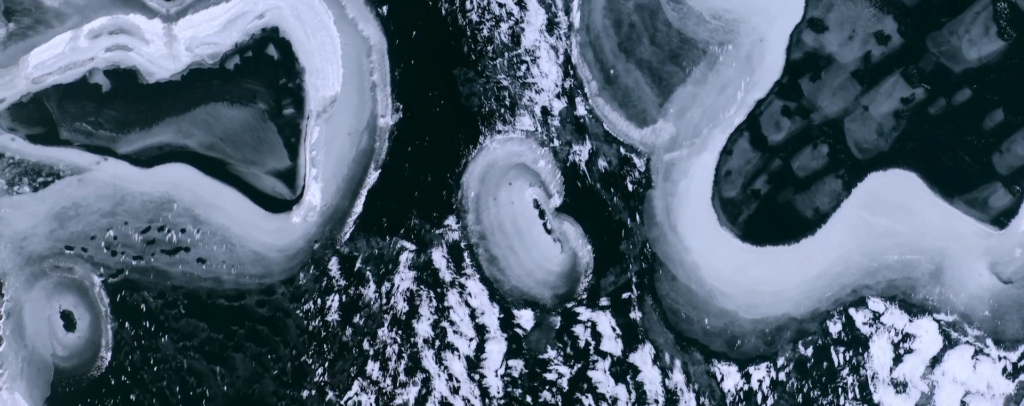

“Serenity”

Peering from directly above, landscapes take on a whole different aspect. That idea is the heart of Vadim Sherbakov’s “Serenity,” filmed by drone. From seething waters and meandering rivers to eroded landscapes and twisting ice, there’s lots of fluid dynamics on display here. (Video and image credit: V. Sherbakov)

Langebaan Lagoon

Strands of green and brown mix in Langebaan Lagoon on the South African coast in this astronaut photograph. The shallow tidal estuary has a sandy floor and, since no river flows into it, the deeper green sections seen here are channels carved solely by the back-and-forth flow of the tides. To the north of the lagoon, Saldanha Bay is a busy hub for fishing and industry. The long reddish line extending into the water is a railroad pier responsible for loading 96 percent of South Africa’s iron ore gets loaded onto ships. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Ghosts of Rivers Past

Artist Dan Coe uses lidar data to create portraits of rivers and their past meanders. Used aerially, lidar produces high-resolution elevation data that provides a glimpse of features that are currently hidden beneath vegetation. With rivers, this means unearthing some of their previous paths. Secondary flows in a river bend erode the bed so that the bend gets more and more strongly curved. Eventually, the river can double back on itself and cut off the long curve. Repeat that process over millennia and you wind up with the complex paths in Coe’s images. (Image credit: D. Coe; via Colossal)

Why Rivers Shift

In their natural state, rivers are variable in their course, shifting and meandering. Sometimes they deposit sediment, and sometimes they erode it. In this video, Grady from Practical Engineering digs into the principles behind these changes. With help from Emriver‘s stream tables, which demonstrate years of changes in a river over minutes, Grady shows how changing the sediment load, flow rate, and other factors in a river affect its course. (Video credit: Practical Engineering)

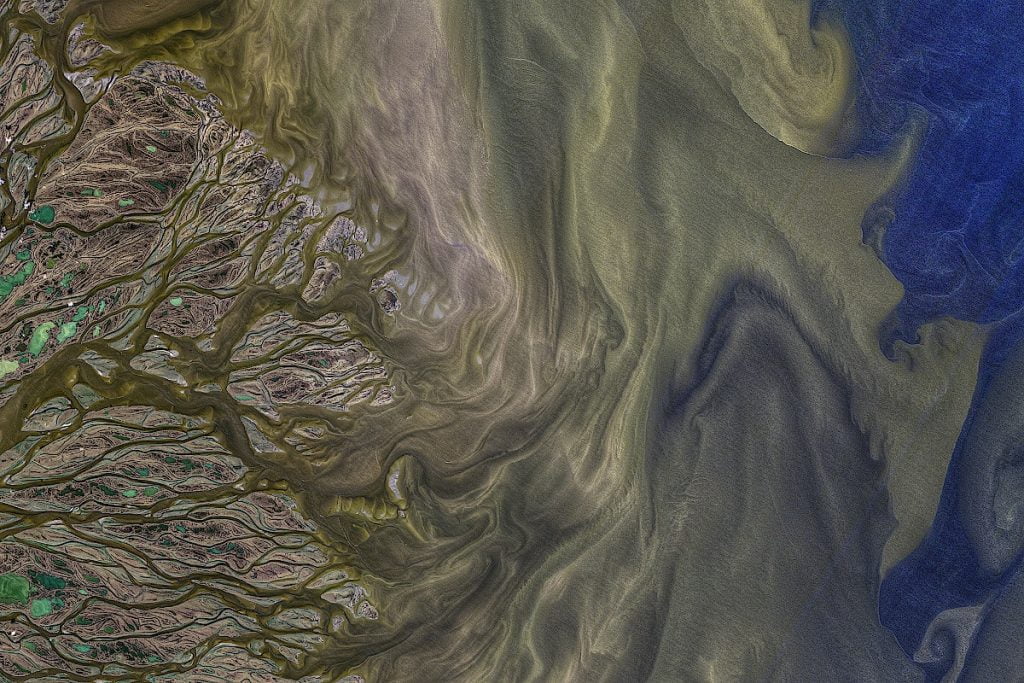

Siberia’s Lena River Delta

As rivers near the sea, they often slow down and branch out, creating intricate paths through delta wetlands. This video explores the Arctic’s largest river delta, that of the Lena River in Siberia, during its spring and summer flood season. The images were all taken by satellite and processed with color enhancements to highlight patterns in the water. Although this is not quite how the area would appear by eye, all of the visible patterns are real. (Image credit: N. Kuring/NASA’s Ocean Color Web; video credit: K. Hansen; via NASA Earth Observatory)

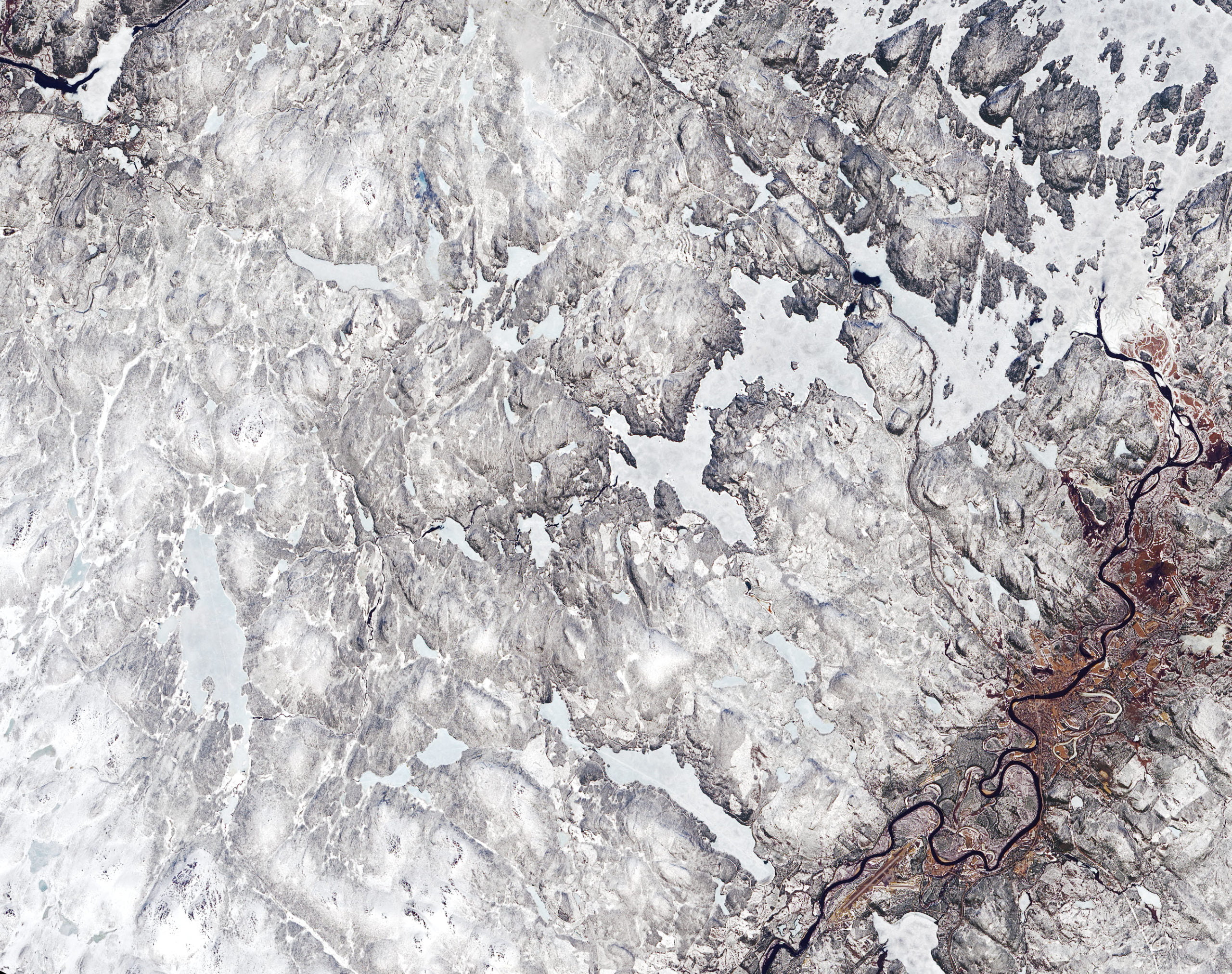

Meandering

The banks of rivers are in constant flux, a pattern most easily captured from above. This satellite image shows a section of the Ivalo River in Finland, swollen with snowmelt after a winter of historic snowfalls. From above we see some of the river’s previous paths. This meandering is a natural result of secondary flows where rivers bend. The water carves away sediment from the outer bank and deposits it on the inner one, exaggerating every curve until the river cuts itself off, leaving behind a sinuous lake detached from the river’s new course. For an interesting (though non-physical) look at meandering, check out this procedural system for generating maps of rivers (thanks to Kam-Yung Soh for sharing). (Image credit: J. Stevens; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Forming an Oxbow

Without human intervention, meandering rivers become more sinuous over time. This is driven by the flow around a river bend, which tends to push sediment from the outer bank of the curve to the inner, making the bend more pronounced. Eventually, loops in the river can pinch off and form a separate oxbow lake, as seen in the animation above and video below.

By studying many photo sequences like this one, researchers have concluded that how quickly a river bend meanders depends on its curvature. In general, the higher the curvature, the faster the river bend will migrate. When rivers deviate from this rule of thumb, it’s typically because part of a river bank is tougher to erode than other sections. (Image and video credit: Z. Sylvester/Geolounge; research credit: Z. Sylvester; via Landsat; submitted by Aatish B.)

Watery Veins

Glacial river veins wend and meander through these aerial photographs of Iceland by photographer Stas Bartnikas. Rivers naturally change their course over time, but here seasonal melts and the slow grinding of glaciers adds further chaos to the scene. Captured from above, these landscapes show the scars of past flows. (Image credit: S. Bartnikas; via Colossal)

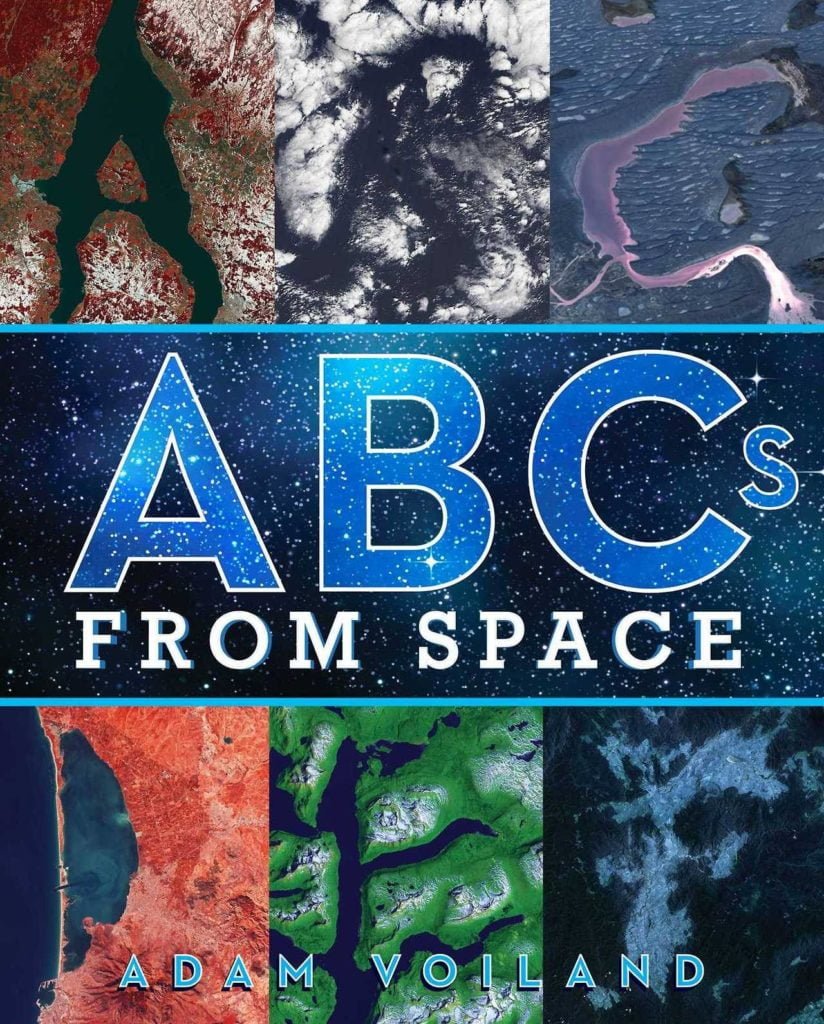

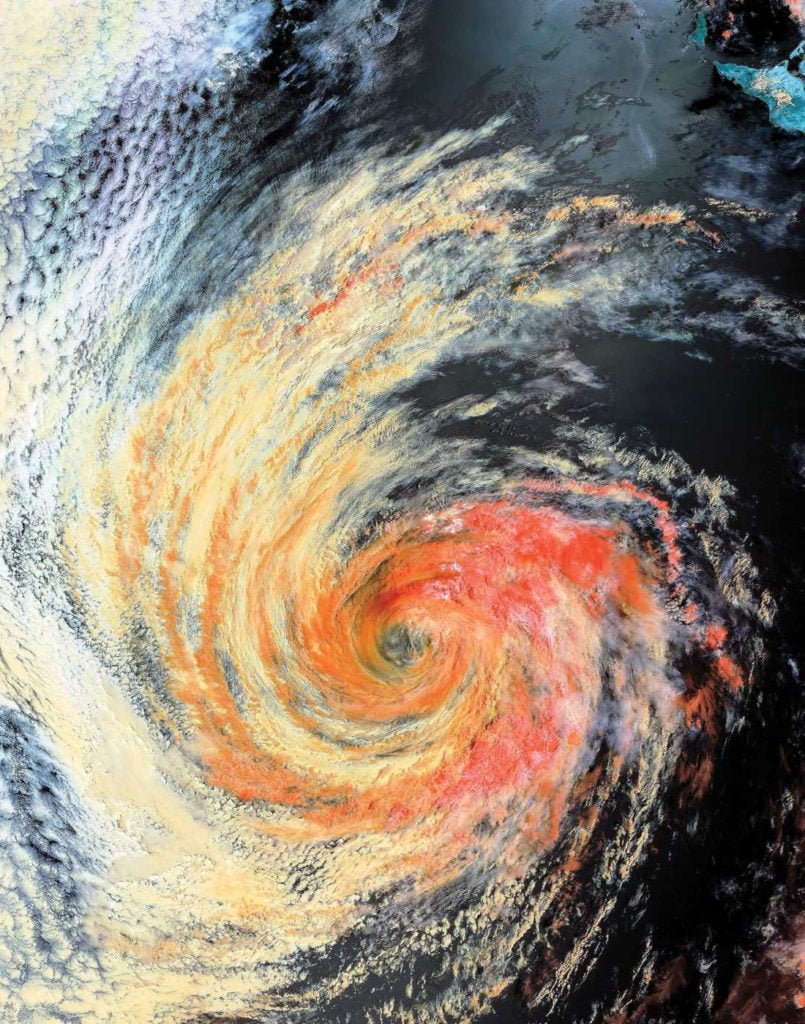

Review: “ABCs From Space”

For me, one of the most fun aspects of studying science is seeking out examples of it in the world around us. Adam Voiland – who writes for NASA Earth Observatory, one of FYFD’s favorite sources for excellent fluids in action – takes this a step further with his children’s book “ABCs From Space: A Discovered Alphabet”. Voiland has sought out satellite imagery from around the world to illustrate all twenty-six letters, creating a lovely book for budding scientists of all sorts.

Each letter has its own full-page image with no added text, like the G and H shown above. Younger children will have fun identifying and tracing out each letter. The back of the book provides more detail for older kids and adults, including brief descriptions of where and what each image shows, a map of all image locations, and some FAQs about satellite imagery and the geology, meteorology, and earth science on display. There are enough specifics to satisfy casual interest, but I suspect that science-inclined adults will find the book a fun springboard for more in-depth discussions with curious kids.

Fluid dynamics itself makes a solid showing in the book. Several letters are formed by vortices (like G above) and various types of clouds, including the ship track clouds (like H) that form when water condenses on aerosols released by ship exhaust. There are also meandering rivers, creeping glaciers, and erosion features among the letters.

I’m often asked about resources for teaching kids about fluid dynamics, and Voiland’s book is a great option for introducing that subject, as well as many other fields of science. (Image credits: A. Voiland/Simon & Schuster)

Disclosure: I received a review copy of this book but was not otherwise compensated by the author or publisher. All opinions are my own. Additionally, this post contains affiliate links. Purchases made using these links do not cost you anything extra but may provide FYFD with a commission. Thanks!