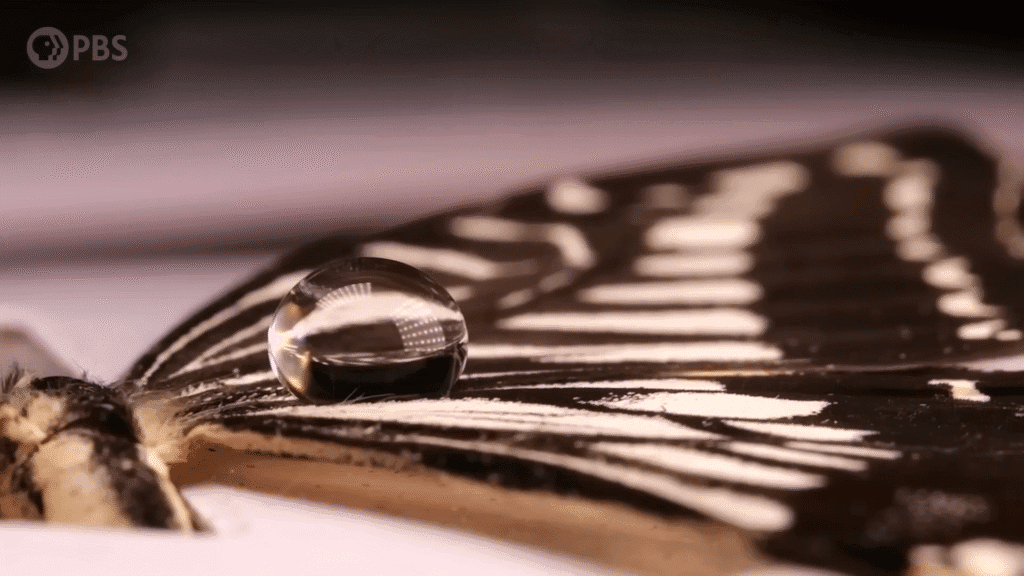

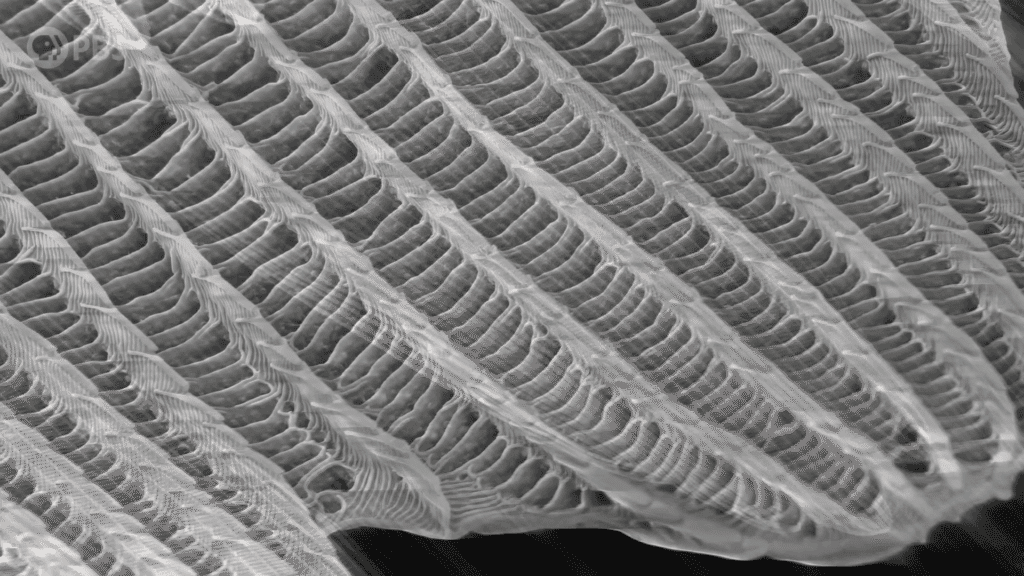

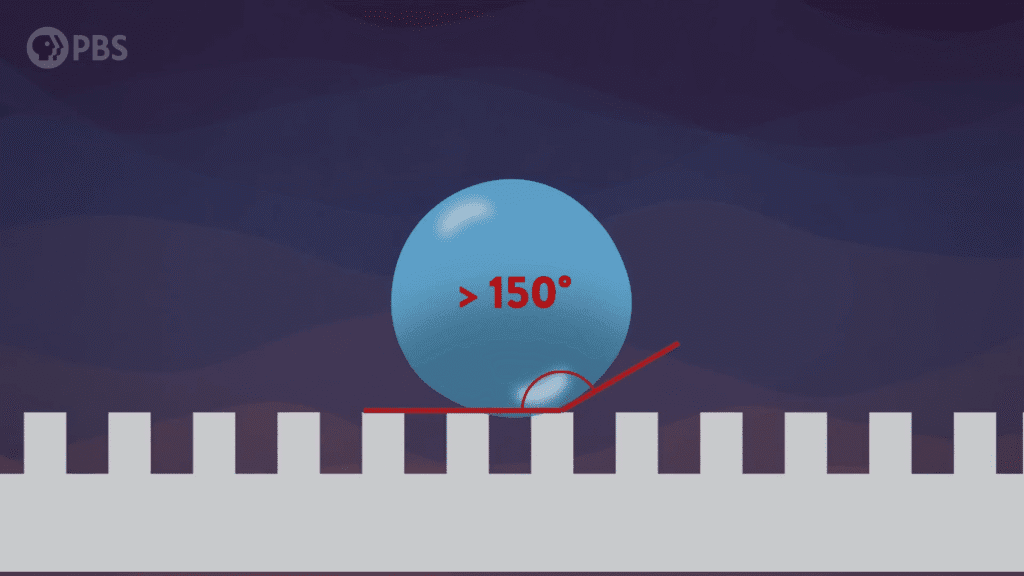

This award-winning macro video shows scattered water droplets evaporating off a butterfly‘s wing. At first glance, it’s hard to see any motion outside of the camera’s sweep, but if you focus on one drop at a time, you’ll see them shrinking. For most of their lifetime, these tiny drops are nearly spherical; that’s due to the hydrophobic, water-shedding nature of the wing. But as the drops get smaller and less spherical, you may notice how the drop distorts the scales it adheres to. Wherever the drop touches, the wing scales are pulled up, and, when the drop is gone, the scales settle back down. This is a subtle but neat demonstration of the water’s adhesive power. (Video and image credit: J. McClellan; via Nikon Small World in Motion)