Hard granular materials — sand, gravel, glass beads, and so on — can flow, but, in narrow regions or under large forces, they can also jam up, essentially turning into a solid. Soft particles can also flow and jam, but do so under different conditions than hard particles. One group of researchers used a custom-built rheometer to measure jamming in soft particles like the hydrogel beads pictured here. They found that they could extend existing models for jamming in hard particles, but they had to rescale the mathematics to account for the way soft particles change their shape under pressure. (Image credit: Girl with red hat; research credit: F. Tapia et al.; via APS Physics)

Tag: hydrogel

Growing Hydrogels in an Active Fluid

Active nematic fluids borrow their ingredients from biology. Using long, rigid microtubules and kinesin motor proteins capable of cross-linking between and “walking” along tubules, researchers create these complex flow patterns. Here, a team took the system a step further by seeding the flow with a hydrogel that turns into a polymer when exposed to light. Then, by shining light patterns on the flow, the scientists can create rigid or flexible structures inside the active fluid. In this case, they show off some of the neat flow patterns they can create. (Video and image credit: G. Pau et al.)

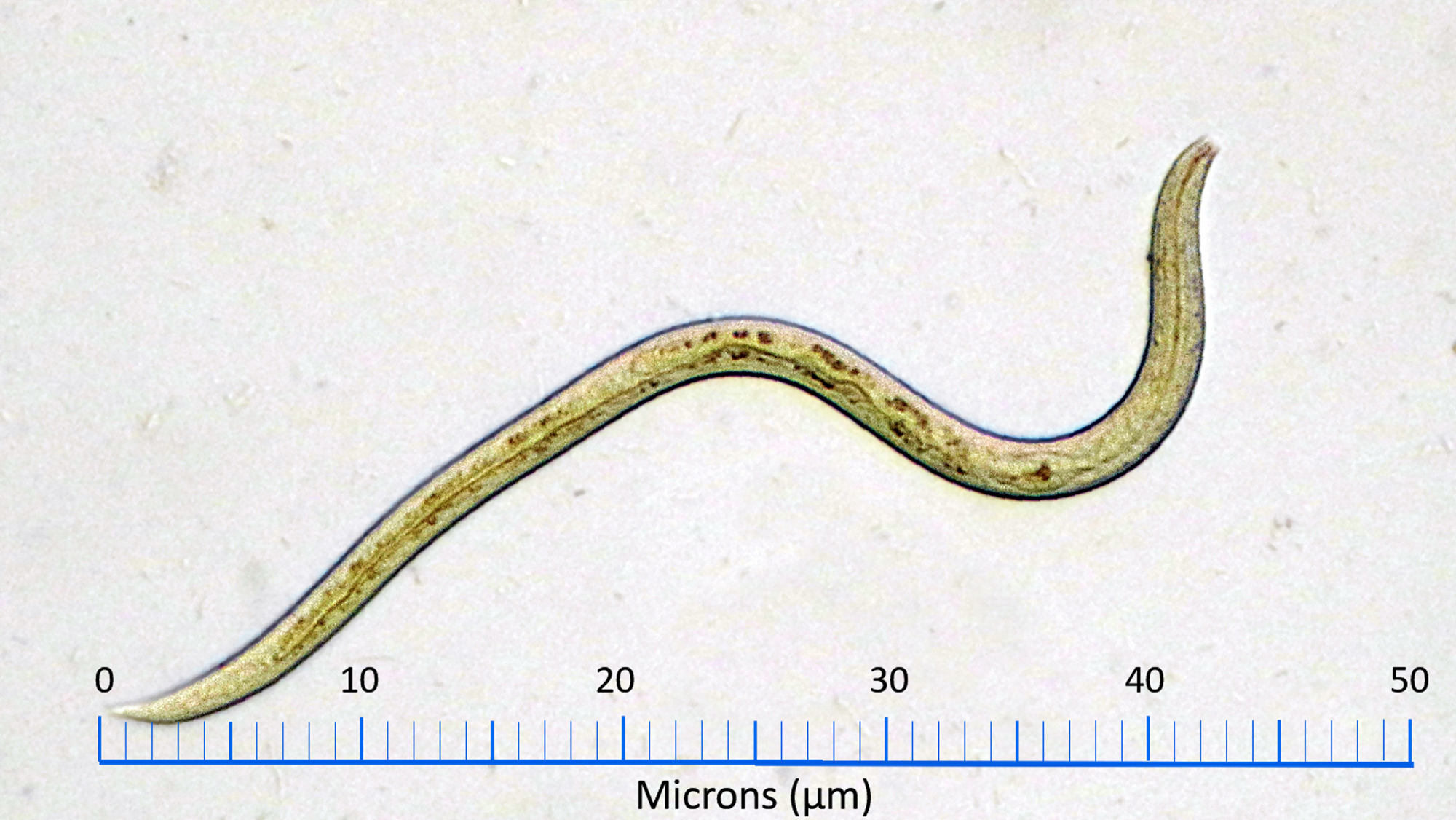

Swimming Through Mud

At the bottom of ponds, nematodes and other creatures swim in a world of mud. They squirm their way through a sediment of dirt particles suspended in water. Mud, of course, is notoriously impossible to see through, so to understand these creatures’ movements, scientists turn instead to biorobotics. Here, a team uses a magnetic head attached to an elastic tail to mimic these tiny creatures.

To drive the robot’s motion, they use an oscillating magnetic field, which forces the magnetic head to rotate. Combined with the elastic tail and the drag caused by surrounding materials, this causes the robot to swim in a fashion similar to its biological inspirations.

A biomimetic robot swims through immersed grains. The robot’s magnetic head is forced with an oscillating magnetic field. It swims through an underwater bed of hydrogel beads, with diameters smaller than that of the robot’s head. To mimic the muddy environment of a pond’s bottom, scientists used a bed of hydrogel beads immersed in water. Looking at the experimental video above, you’ll see no sign of the beads. That’s because the hydrogel beads have nearly the same index of refraction as water. Once you pour water in, they seem to disappear. That allows the researchers to focus instead on the robot’s motion. In other experiments, they added dye to the beads so that they could see how they moved around the robot.

They found that the robot’s motion fluidizes the grains around it. Effectively, the robot’s motion creates an area with fewer grains and more water for it to move through. Once it’s passed, however, more grains settle in, and the bed returns to a denser packing. (Image credit: nematode – P. Garcelon, experiment – A. Biswas et al.; research credit: A. Biswas et al.)

Tougher Hydrogels

Hydrogels are soft, stretchy solids made from polymer chains immersed in water. Engineers hope these materials will be good candidates for medical implants, but to reach that goal, hydrogels need to be durable enough to withstand repeated stretching and contortion without tearing. One team has built a better hydrogel by encouraging entanglement within the gel’s polymer network.

The polymers inside a hydrogel form their network with two main components: physical entanglements between polymer chains and chemical cross-links. If you imagine the polymers as a tangle of yarn, the cross-links would be spots where pieces of yarn are knotted together and the entanglements are spots where strands wrap and cross without knotting. If you pull on the network, cross-links (knots) will allow very little stretching, whereas the looser entanglements can stretch and deform without tearing. In a hydrogel with lots of entangled polymers but very few cross-links, the material is strong and stretchy without becoming brittle or easily torn. (Video credit: Science; research credit: J. Kim et al.)

Alien Eggs? A Virus?

Nope, they’re hydrogel beads! The team at Chemical Bouillon seem to have once again coated them in something like paint before placing them in water. As the gel beads absorb water, they expand, tearing through their coating. The result is weirdly mesmerizing and kind of creepy. It’s no wonder that special effects artists have historically turned to fluids for sci-fi films! (Image and video credit: Chemical bouillon)

Expanding Water Beads

In this timelapse, we see hydrogel beads expanding as they absorb water. There are some interesting subtleties to the physics here. Notice how, in the Petri dish segments, the beads shift from a single crystalline structure to several smaller structures. I suspect those shifts are driven by the dropping water level, which changes how surface tension interacts with the beads’ shape to create attractive forces between beads.

Another interesting point comes as the beads expand through and out of the glass of water. Initially, the water level doesn’t change in the glass. This is because the water beads are taking up the same volume as the water that they’ve absorbed. But once the beads emerge past the water’s initial height, the water level drops dramatically. That’s because the beads are still absorbing what little water is left and continuing to expand in volume. (Image and video credit: Temponaut)

Paint Versus Hydrogel

In this bizarre short film, we get to see a battle between dissolution and absorption. I think the Chemical Bouillon team has coated hydrogel beads in a layer of paint and then immersed them in water. As the beads absorb water, they expand and grow, tearing their fragile outer layer of paint to smithereens.

One thing that struck me when watching several of the sequences is just how regular the hole spacing in the paint is for the round hydrogels. That hints at an orderly breakdown in the solid paint layer while the interior hydrogel polymer symmetrically expands. It’s a little like watching holes grow in a splash curtain. (Video and image credit: Chemical Bouillon)

“Viscoelasticity Gives You Wings!”

What happens when you drop a hydrogel bead on a water droplet? Because of the hydrogel’s viscoelasticity and its hydrophilic nature, the rebounding bead carries the droplet with it. As seen in the video above, when the impact energy is small enough, the droplet forms a reverse crown during lift-off, kind of like giving the hydrogel bead a skirt. The key feature for lift-off is the bead’s deformation on impact. Because the hydrogel widens at its base, it is sometimes able to push the entire droplet off its initial footprint and detach it from the surface. (Image, research, and video credit: R. Rabbi et al.)

The Elastic Leidenfrost Effect

Drop some hydrogel beads in a hot frying pan and they’ll bounce, hiss, and screech. Normally, if you drop a ball, it bounces to ever smaller heights until it comes to rest. In contrast, on a hot surface the hydrogel can bounce to a steady height for minutes at a time, raising a question: where does it get the energy for its incessant bounce?

Upon close examination of the impact, researchers found the hydrogel beads are actually slapping the surface over and over on each bounce. The frequency of the slapping exactly matches that of the audible screech, so what you’re actually hearing is this bounce-slap. Now what causes the slapping?

Contact with the hot surface vaporizes some of the water inside the hydrogel. If it were a droplet, this vapor would form a thin, almost frictionless layer the droplet could glide on; that’s the classic Leidenfrost effect. Here the shell of the bead prevents that until the pressure really builds up. When the pressure gets high enough, the vapor finally escapes, opening up a gap. As the gap reaches its largest point, the bead rebounds elastically, bringing it back in contact with the surface and starting the process again. Each of these cycles acts like a tiny engine, harvesting energy that drives the larger bounce. This elastic Leidenfrost effect may be particularly helpful in soft robotics, providing robots with a new mechanism for movement. (Image and video credit: S. Waitukaitis et al.,arXiv)

Soft Robots

A research group at MIT has created a new class of fast-acting, soft robots from hydrogels. The robots are activated by pumping water in or out of hollow, interlocking chambers; depending on the configuration, this can curl or stretch parts of the robot. The hydrogel bots can move quickly enough to catch and release a live fish without harming it. (Which is a feat of speed I can’t even manage.) Because hydrogels are polymer gels consisting primarily of water, the robots could be especially helpful in biomedical applications, where their components may be less likely to be rejected by the body. For more, see MIT News or the original paper. (Image credit: H. Yuk/MIT News, source; research credit: H. Yuk et al.)