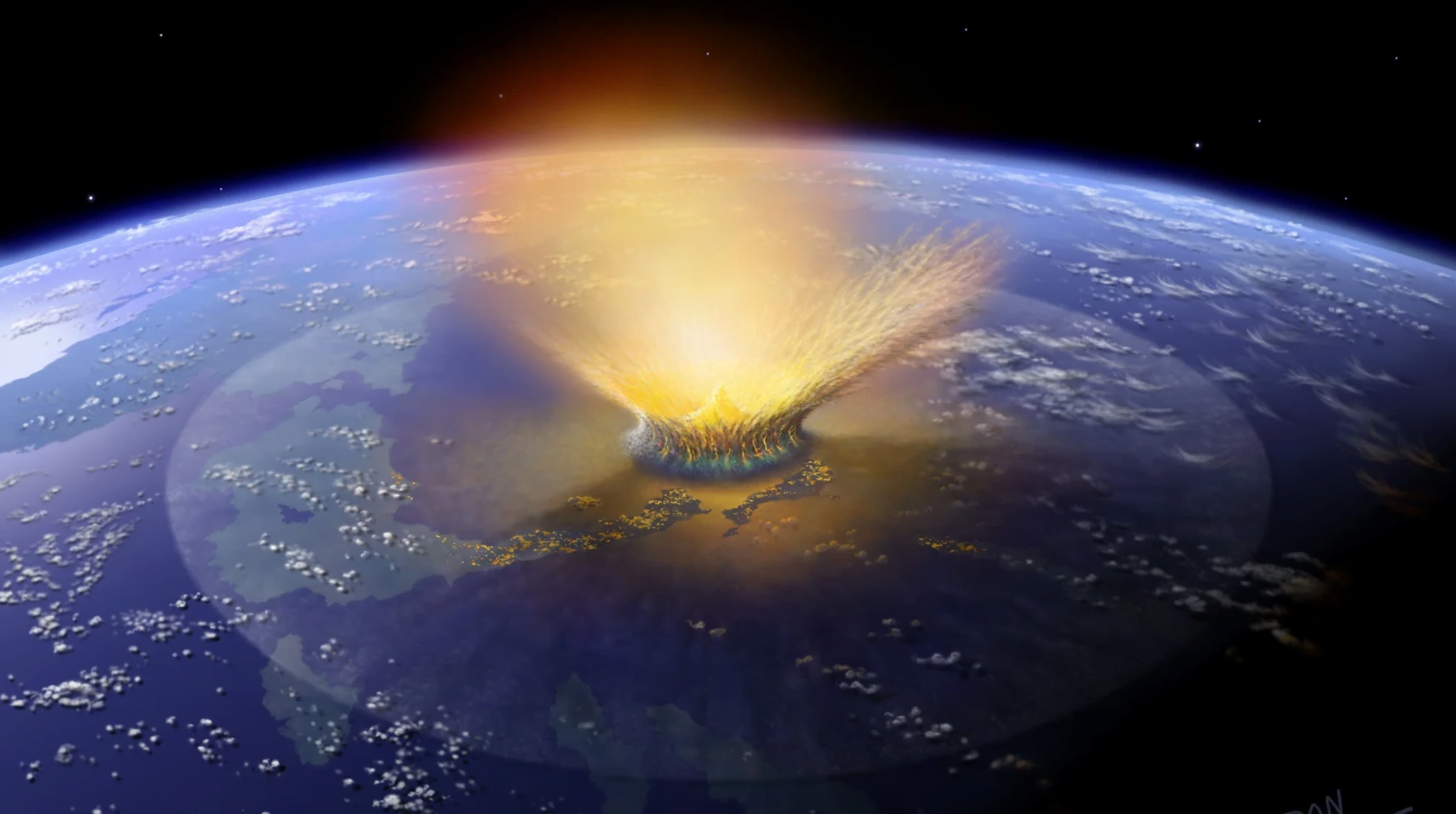

66 million years ago an asteroid struck offshore of what is now Chicxulub near the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The impact and its aftermath are widely credited with a mass extinction that wiped out 75% of plant and animal life on Earth, including non-avian dinosaurs. Since the impact occurred in shallow waters, it also generated a tsunami, one over 30,000 times bigger than any in recorded history.

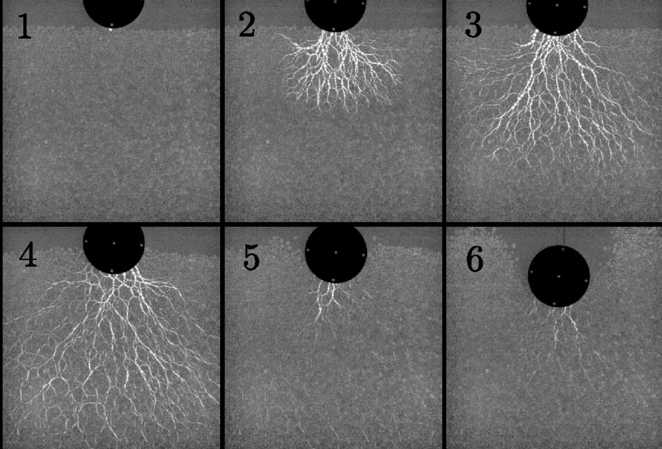

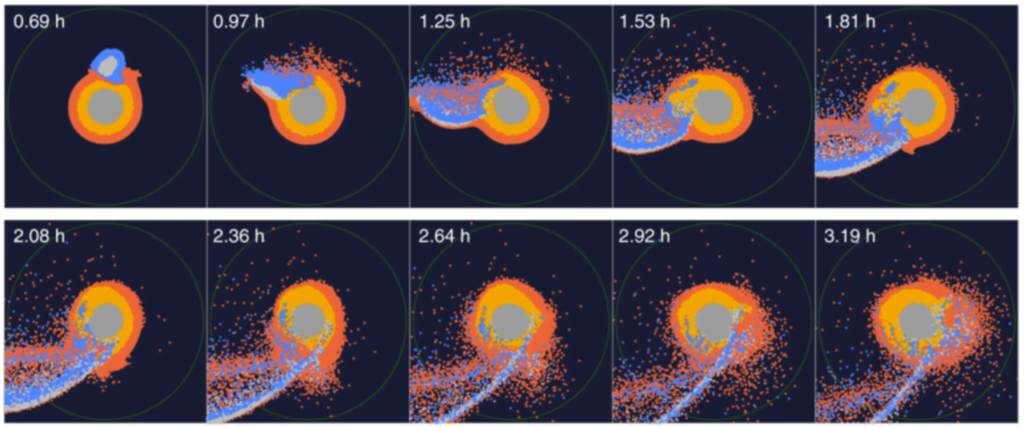

In this simulation, researchers show how that tsunami spread globally. The initial wave was about a mile high but stretched up to about 2.5 miles as it rushed ashore. Worldwide, every shoreline saw flows at 20 cm/s or higher as the wave hit. In the image above, black areas show the landmasses as they existed at the time, with modern borders shown in white outline. To watch the video, click on the image or head to NOAA’s visualization.

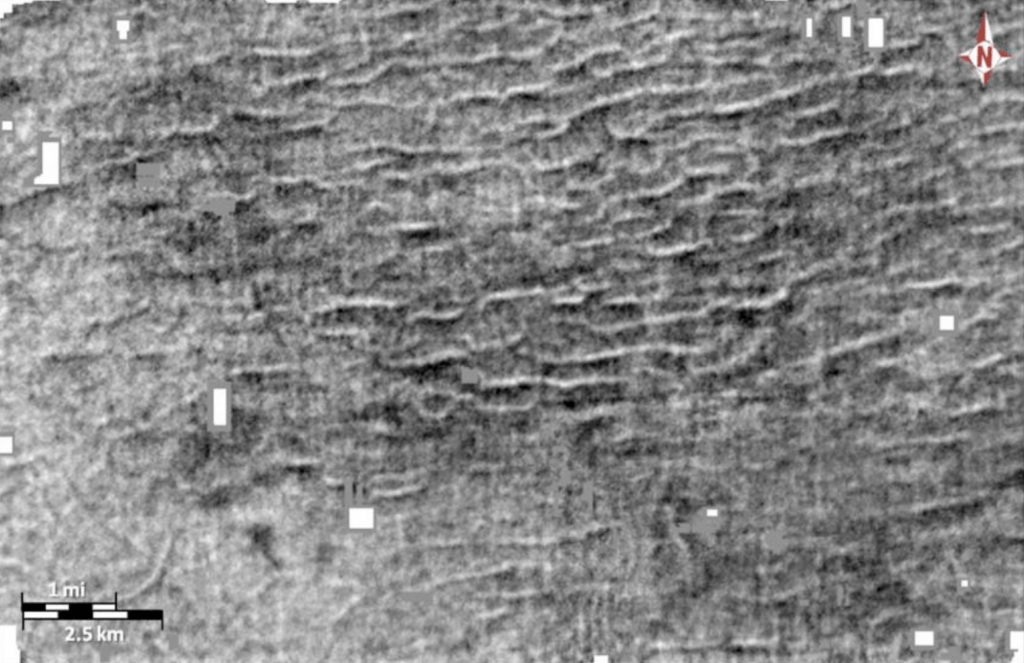

You may wonder how scientists can validate a simulation like this one, which so wildly exceeds any recorded event. One way they judged these results is by looking at the sedimentary records of the seafloor. Their results show flows large enough to scour the seafloor and disrupt any sedimentary records in those areas, and, sure enough, those regions hold no records older than the asteroid’s impact. That alignment between the geological record and the simulation’s highest flow areas helps establish confidence in the results. (Image credit: illustration – SWRI/D. Davis, simulation – NOAA; research credit: M. Range et al.; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)