Tsunamis are devastating natural disasters that can strike with little to no warning for coastlines. Often the first sign of major tsunami is a drop in the sea level as water flows out to join the incoming wave. But researchers have now shown that magnetic fields can signal a coming wave, too. Because seawater is electrically conductive, its movement affects local magnetic fields, and a tsunami’s signal is large enough to be discernible. One study found that the magnetic field level changes are detectable a full minute before visible changes in the sea level. One minute may not sound like much, but in an evacuation where seconds count, it could make a big difference in saving lives. (Image credit: Jiji Press/AFP/Getty Images; research credit: Z. Lin et al.; via Gizmodo)

Tag: tsunami

Tongan Eruption

In January 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano erupted spectacularly, sending waves around the world through the air, water, and ground. In many ways, it was unlike any eruption scientists have observed, though they think it bears similarities to the 1883 eruption at Krakatoa. This video summarizes some of the research to come out of the eruption, looking at how waves propagated, what aerosols the volcano pushed high into the atmosphere, and what the long-term effects of the eruption may be. (Video credit: Science)

The Chicxulub Impact’s Tsunami

66 million years ago an asteroid struck offshore of what is now Chicxulub near the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The impact and its aftermath are widely credited with a mass extinction that wiped out 75% of plant and animal life on Earth, including non-avian dinosaurs. Since the impact occurred in shallow waters, it also generated a tsunami, one over 30,000 times bigger than any in recorded history.

Snapshot showing the spreading tsunami after the asteroid’s impact. Click on the image to go to NOAA’s website and watch the video. In this simulation, researchers show how that tsunami spread globally. The initial wave was about a mile high but stretched up to about 2.5 miles as it rushed ashore. Worldwide, every shoreline saw flows at 20 cm/s or higher as the wave hit. In the image above, black areas show the landmasses as they existed at the time, with modern borders shown in white outline. To watch the video, click on the image or head to NOAA’s visualization.

You may wonder how scientists can validate a simulation like this one, which so wildly exceeds any recorded event. One way they judged these results is by looking at the sedimentary records of the seafloor. Their results show flows large enough to scour the seafloor and disrupt any sedimentary records in those areas, and, sure enough, those regions hold no records older than the asteroid’s impact. That alignment between the geological record and the simulation’s highest flow areas helps establish confidence in the results. (Image credit: illustration – SWRI/D. Davis, simulation – NOAA; research credit: M. Range et al.; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

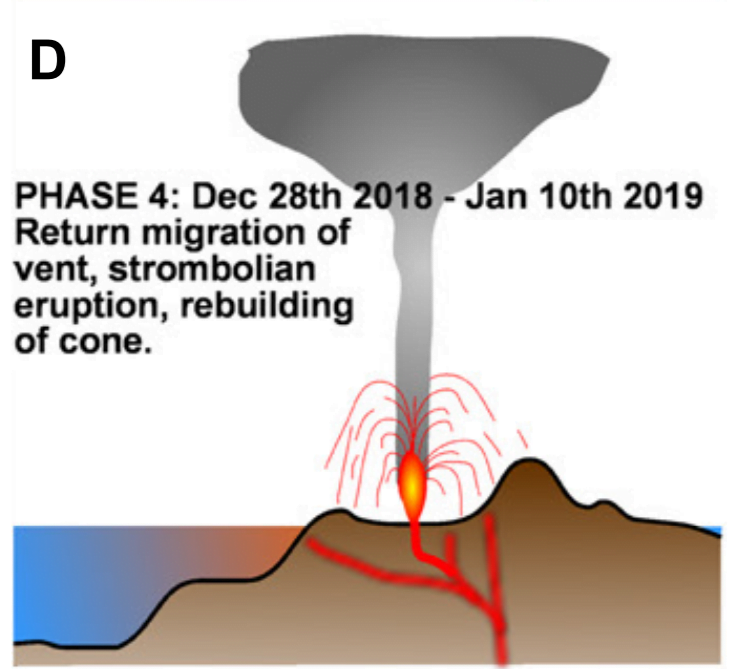

Deciphering Krakatau

In 1883, the eruption of Krakatau (also called Krakatoa) shook the world, sending shock waves and tsunamis ricocheting across the globe. Some of the smaller waves hit shorelines in the Atlantic and Pacific that were entire continents and ocean basins away from the original explosion. At the time, scientists were so perplexed by the phenomenon that they blamed coincidental earthquakes for the wave action.

Only when Tonga experienced a similarly devastating volcanic eruption earlier this year were scientists able to verify what they’d long suspected: these smaller tsunamis were not caused by solid material displacing water; instead they are the result of atmospheric pressure waves coupling to the ocean. Follow the full story over at Quanta. (Image credit: M. Barlow; via Quanta; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

How Tsunamis Cross the Ocean

Last week an earthquake in Chile raised concerns over a possible tsunami in the Pacific. This animation shows a simulation of how waves would spread from the quake’s epicenter over the course of about 30 hours. In the open ocean, a tsunami wave can travel as fast as 800 kph (~500 mph), but due to its very long wavelength and small amplitude (< 1 m), such waves are almost unnoticeable to ships. It’s only near coastal areas, when the water shallows, that the wave train slows down and increases in height. Early in the video, the open ocean wave heights are only centimeters; note how, at the end of the video, the wave run-up heights along the coast are much larger, including the nearly 2 meter waves that impacted Chile. The power of the incoming waves in a tsunami are not their only danger, though; the force of the wave getting pulled back out to sea can also be incredibly destructive. (Video credit: NOAA/NWS/Pacific Tsunami Warning Center; via Wired)

“Tidal Wave” vs. “Tsunami”

This is part of the trouble when the same term has a scientific meaning and a lay meaning. See also: fluid.

Tsunami Simulation

This simulation shows how tsunami waves are expected to spread from the epicenter of the Japanese magnitude-8.9 earthquake. Note the complicated interference and reflection patterns. The main wavefront moved at a speed of about 230 m/s (830 km/h) between Japan and Hawaii.