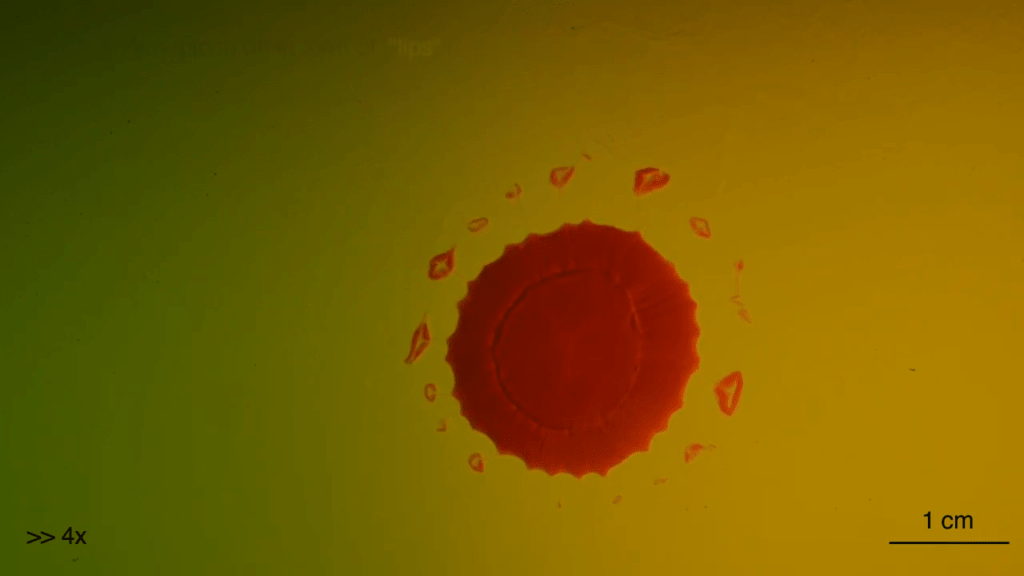

When surface tension varies along an interface, fluids move from regions of low surface tension to higher surface tension, a behavior known as the Marangoni effect. Here, a drop of (dyed) water is placed on glycerol. The two fluids are miscible, but water has much a lower viscosity and density yet a higher surface tension. The drop’s interface quickly becomes unstable; viscous fingers form along the edge as the less viscous water pushes into the more viscous glycerol. Eventually, the surface-tension-driven Marangoni flow breaks those fingers off into lip-like daughter drops. The researchers also show how the interplay between viscosity and surface tension affects the size of fingers that form by varying the water/glycerol concentration. (Image and video credit: A. Hooshanginejad et al.)

Tag: 2021gofm

Instabilities on Instabilities

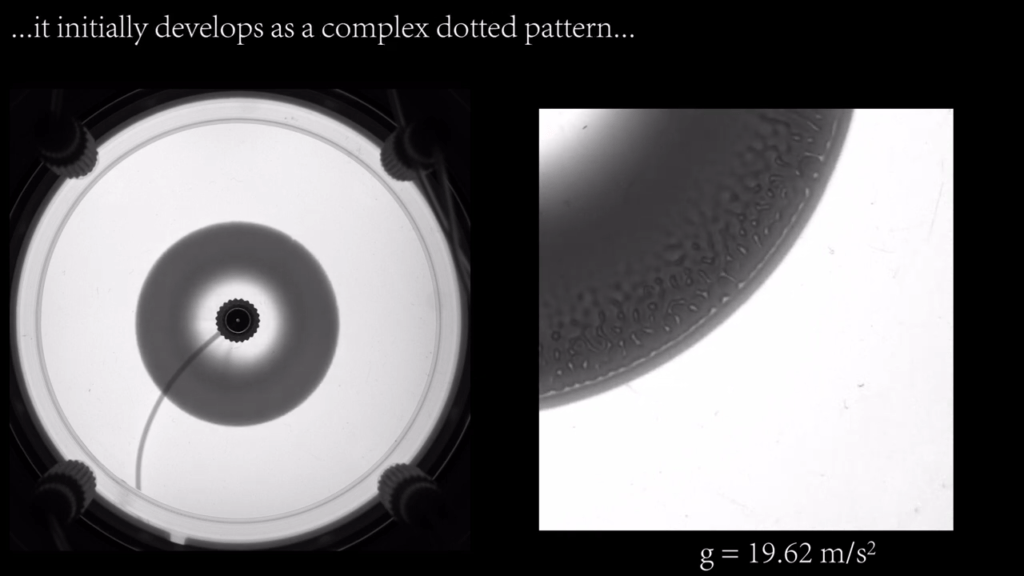

The world of fluid instabilities is a rich one. Combine fluids with differing viscosities, densities, or flow speeds and they’ll often break down in picturesque and predictable manners. Here, researchers explore the Rayleigh-Taylor instability (RTI), which occurs when a denser fluid sits above a less dense one (in a gravitational field). It’s an extremely common instability, showing up in both the cream in your ice coffee and the shape of a supernova’s explosion. It’s very difficult to set up and observe, though, which is where the real cleverness of this experiment stands out.

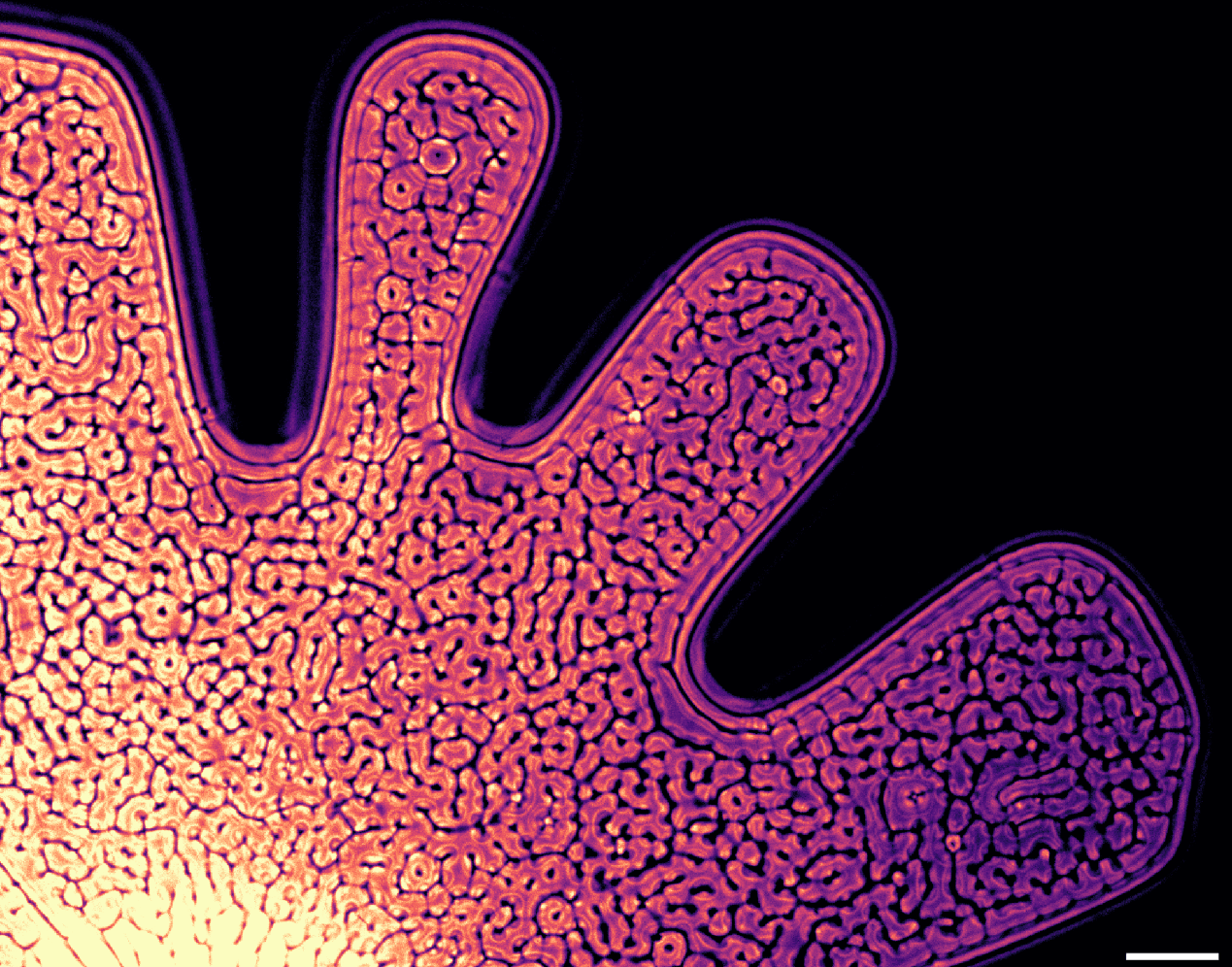

To study the RTI, these researchers first created another instability, the Saffman-Taylor instability. They filled the space between two glass plates with a viscous fluid, then injected a less viscous one. That created the distinctive viscous fingering pattern seen in the top image. In addition to being less viscous, the injected fluid was also less dense. As it pushed into the original fluid, it displaced some of it, creating a three-layer structure with dense fluid over less-dense fluid over dense fluid. That laid the groundwork for the Rayleigh-Taylor instability form.

A side-view through the fluid mixture shows the characteristic mushroom-like plume of the Rayleigh-Taylor instability. Check out the cell-like pattern distributed across the fluid in the top image. These are plumes formed in the RTI as dense fluid sinks into the less-dense fluid below it. From the side (see second image), each plume takes on the distinctive mushroom-like shape of a Rayleigh-Taylor instability. Given time, the two fluids mix and the cellular pattern disappears. But until then, this set-up uses one instability to study a second one. How cool is that?! (Image and research credit: S. Alqatari et al., see also)

Mixing With E. Coli

What happens when a flow meets swimming micro-organisms? Does the flow affect the swimmers? And how do the swimmers affect the flow in turn? Those are the questions behind the experiment seen here. The apparatus contains a thin layer of saline water with swimming E. coli. Electromagnetism is used to mix the fluid in an array-like pattern that triggers chaotic mixing. To visualize what’s going on, dye is introduced into the right half of the image, while the left half remains undyed.

On the right side of the image, bright blue and white mark areas of high dye concentration, where strong mixing occurs. On the undyed left side of the image, pale blue streaks mark areas where E. coli are clustered. By comparing the two, we see that the micro-swimmers are clustered in the very same regions of flow marked by strong mixing. This result suggests strong interactions and the potential for feedback between the mixing flow and the swimmers. (Image and research credit: R. Ran et al.; see also 1 and 2)

Chemical Flowers

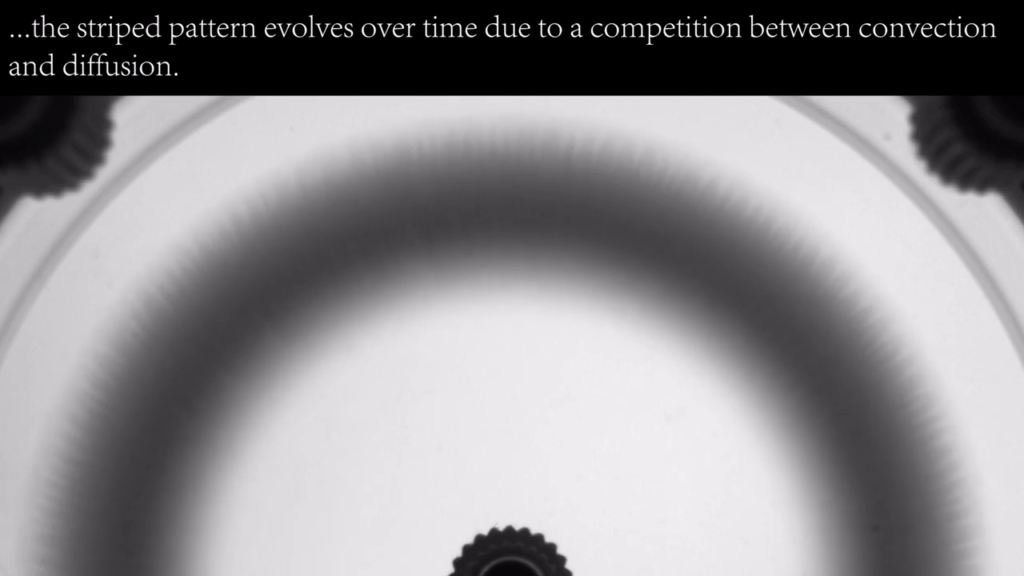

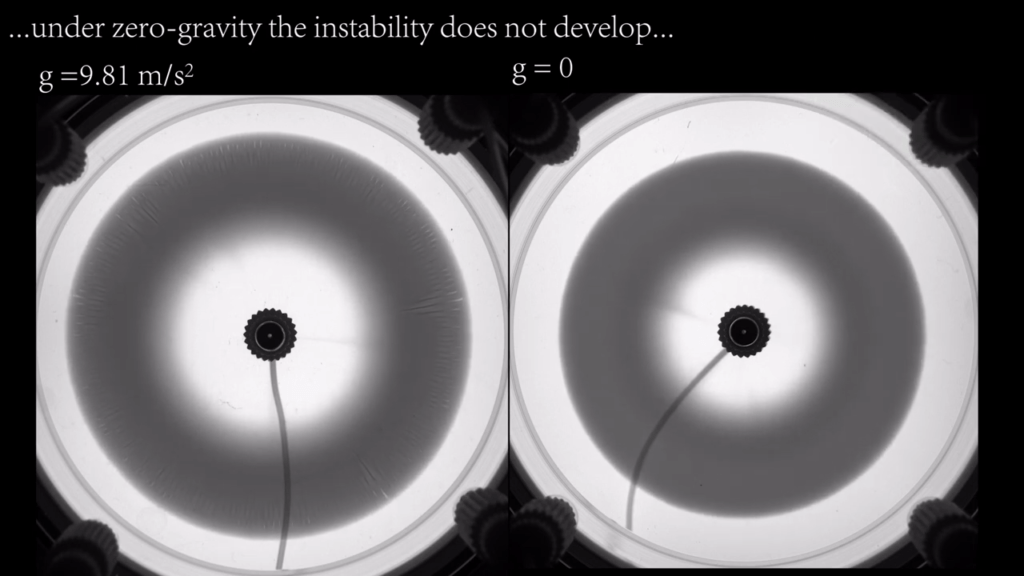

These “flowers” blossom as two injected chemicals react in the narrow space between two transparent plates. The chemical reaction produces a darker ring that develops a streaky outer edge due to competition between convection and chemical diffusion.

To show how gravity affects the instability, the researchers repeated the experiment on a parabolic flight. In microgravity conditions, no instability formed. That’s exactly what we’d expect if convection (i.e. flow due to density differences) is a major cause. No gravity = no convection. In contrast, under hypergravity conditions, the instability was initially spotty before developing streaks. (Image and video credit: Y. Stergiou et al.)

Leaky Resonance

Some resonators aren’t perfect — nor are they meant to be! Here, researchers experiment with resonance using a disk shaking up and down over a pool of water. The disk never touches the water, but its movement makes the air above the water move in and out, like a miniature, changeable wind. The air flow distorts the water surface, creating waves just tens of microns high. Beneath the disk, the water forms standing waves, indicating resonance.

But the waves don’t stay under the disk. Beyond its edge, we see traveling waves moving outward, carrying some of the disk’s energy with them. This leakage is actually how many musical instruments, like a guitar, work. When the guitar strings are plucked, their vibrations are transmitted into the body of the guitar through its bridge, where the strings are anchored. The body acts as a resonator, amplifying the sound, some of which leaks out the sound hole. (Image and video credit: U. Jain et al.)

Diving Together

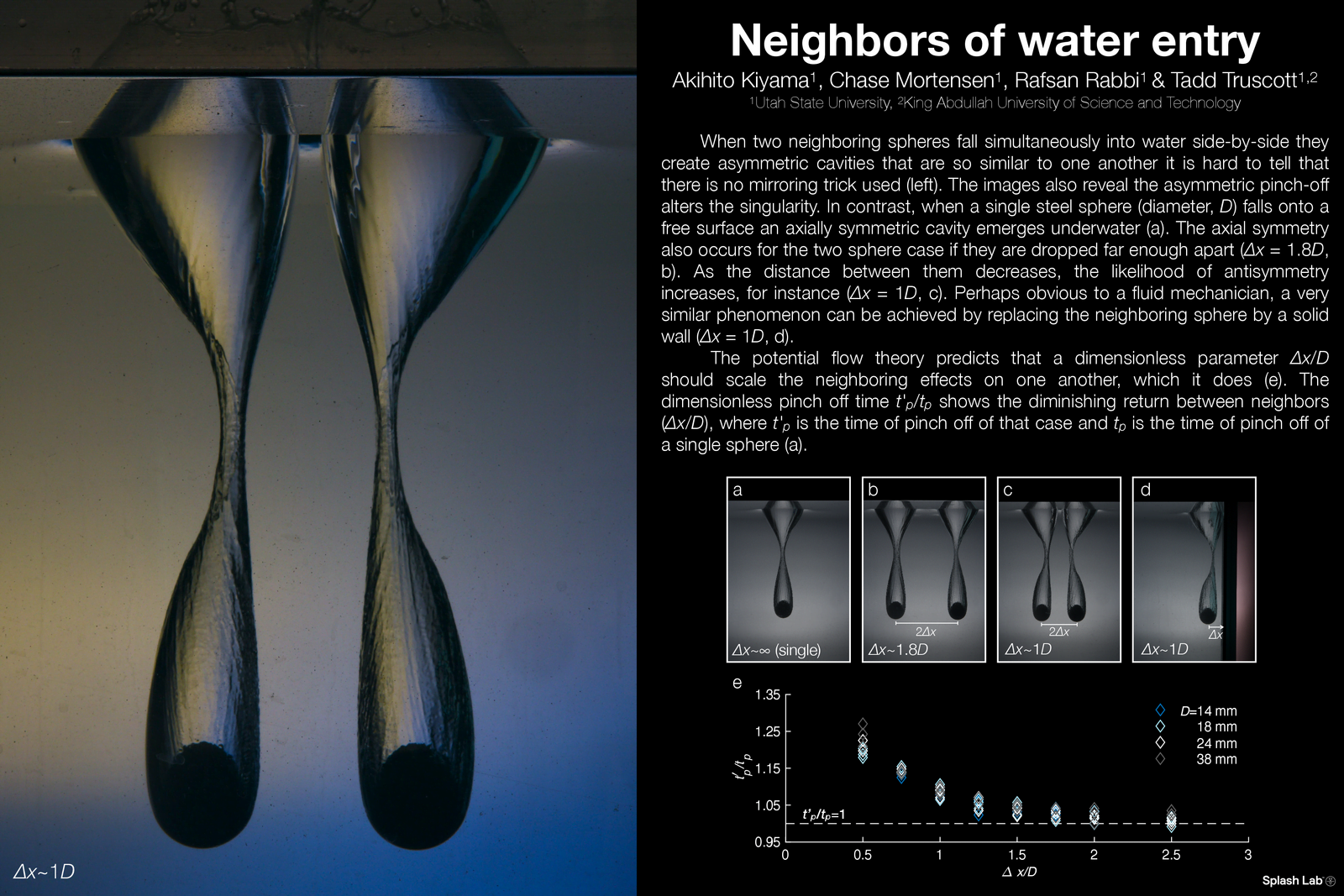

Two spheres dropped into water next to one another form asymmetric cavities. A single ball’s cavity is perfectly symmetric, and so are two spheres’, provided they are far enough apart. But for close impacts, the spheres influence one another, creating a mirror image. The same asymmetric cavity also forms when a sphere is dropped near a wall. In fluid dynamics, this trick — using two mirrored objects in place of a wall — is used to make calculating certain flows easier! (Image credit: A. Kiyama et al.)

Aerated Faucets

So much goes on in our daily lives that we never see. But with the power of the smartphones in our pockets, we can catch more than ever before, as illustrated in this video. Here a researcher uses the standard “slo-mo” (240 fps) video mode on a smartphone to look at the flow from a typical kitchen faucet. Household faucets often have an aerator that adds air bubbles to the flow, something that’s particularly visible in slow motion at high flow rates. What you can see depends on more than just the frame rate, though. Without strong illumination — provided in this case by sunlight — you could easily miss the cloud of droplets ejected by the faucet. (Image and video credit: M. Mungal)

Meet BILLY

Many wings in nature are not rigid. Instead they flex and curve with the flow. Here researchers imitate that phenomenon with BILLY (Bio-Inspired Lightweight and Limber wing prototYpe). Using an evolutionary-style algorithm, BILLY determines its own optimal flapping characteristics to maximize performance. Its flexible membrane-style wing actually performs better than a rigid wing! Check out the end of the video for some flow visualization of the leading edge vortex. (Image and video credit: A. Gehrke et al.)

Particle-Filled Coatings

Pulling a solid object from a liquid bath can coat it in a thin layer of liquid. The thickness of the coating layer depends on the speed at which the object is removed. Introducing particles into the liquid bath adds a new dimension to the coating problem, namely the size of the particles. In this poster, researchers demonstrate some of the coatings possible in a mixture with particles of more than one size. It’s even possible, they note, to filter out particles of a certain size by carefully selecting the removal speed. (Image credit: D. Jeong et al.)