In 1827, botanist Robert Brown observed an odd jittery motion of particles as he watched grains of pollen floating in water under his microscope. He saw the random motion also with inorganic — which is to say definitely Not Alive — particles as well. But it was Einstein nearly 80 years later who figured out how to connect this observable motion to atoms. Einstein realized Brown’s particles were being constantly jostled by atomic collisions, and, with a little work, we could use those moving particles to determine Avogadro’s number. Steve Mould walks you through the whole story in this video. (Video and image credit: S. Mould)

Tag: molecular diffusion

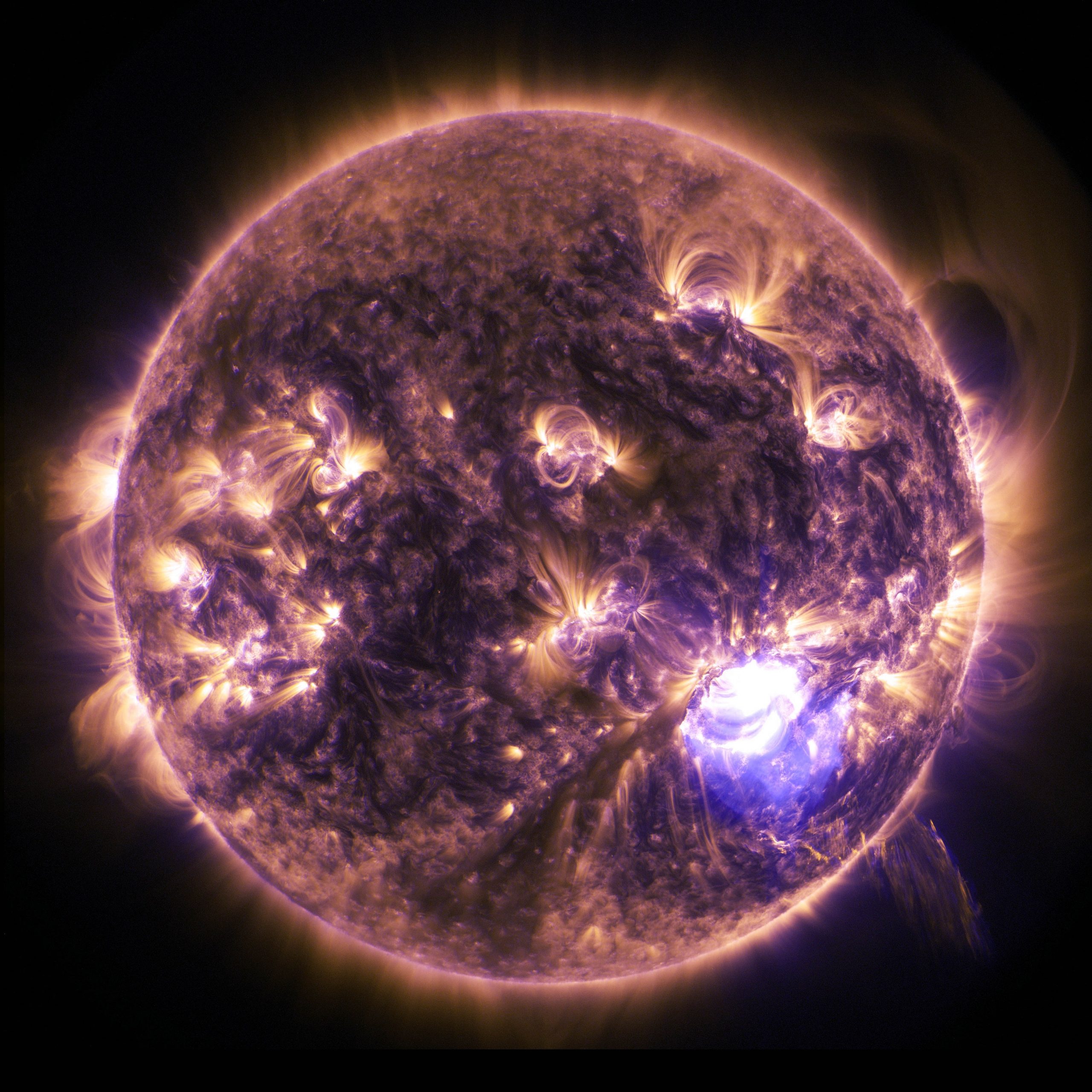

Searching For Solar Neutrinos

An experiment in Italy has reported new findings confirming a long-standing theory of nuclear fusion in our Sun. The researchers were able to detect neutrinos released by the relatively rare fusion of carbon and nitrogen. But catching those neutrinos took an impressive fluid dynamical feat.

The Borexino solar-neutrino detector is essentially an enormous nylon balloon, filled with liquid hydrocarbons, immersed in water, and buried beneath a kilometer of rock. Most neutrinos fly through this milieu unhindered, but a few collide with hydrocarbon molecules, creating streaks of light picked up by the detector.

The challenge in distinguishing solar carbon-nitrogen neutrinos comes from an isotope in the balloon’s nylon lining, which slowly leaks into the detector. The noise caused by the leaking isotope is easily confused with the true solar signal. To tamp down on that noise level, the researchers took elaborate steps to ensure that all 278 tonnes of liquid in the detector remained at exactly the same temperature, thereby eliminating convection in the detector. With only molecular diffusion to move the noisy isotopes, the researchers held the liquid incredibly still. One team member described the fluid as moving only tenths of a centimeter a month! (Image credit: NASA SDO; via Nature; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Water Anoles Breathe Underwater

Meet the water anole, a small lizard native to the tropics of Central America. While studying these anoles, researchers discovered that they could flee underwater and remain submerged for 16 minutes or more at a time. Curious to see how the lizard manages this feat, they filmed them underwater, discovering that the anole seems to exhale a small bubble that sticks on its face and then re-inhale it.

How exactly this built-in “scuba gear” works is still under investigation, but here’s my guess. Fresh oxygen can diffuse from water into a bubble; some insects use this to breathe underwater. The natural, random motion of molecules tends to cause chemicals to move from areas of high concentration to those of low concentration. But this molecular diffusion is extremely slow. That tiny bubble you see isn’t around long enough for any significant molecular diffusion of fresh oxygen. But what if the surface of the bubble is actually much larger?

Notice the silvery shininess we see on the anole. That’s because most of the lizard isn’t actually wet. The anole is superhydrophobic, so its skin has trapped a thin layer of air that appears to extend over a large part of its body. I think perhaps the anole has fresh oxygen diffusing into the air layer across most of its skin, and the large bubble it inhales and exhales serves as a sort of pump to help draw that fresh oxygen through the air layer and into its body. That could help explain how the anole can stay submerged for so long.

As researchers continue to investigate this little aquanaut, it will be interesting to discover just what its secrets are! (Image and video credit: L. Swierk; via Gizmodo)

Ink Drops Spreading

Ink drops atop a layer of glycerol spread in a beautiful fan of blue and white. The ink’s motion is the result of two processes: molecular diffusion and the Marangoni effect. Molecular diffusion is the mixing that occurs due to the random background motion of molecules. Since glycerol is a very viscous liquid, the ink is quite slow to spread in this manner.

The second factor, the Marangoni effect, is driven by differences in surface tension. The ink and glycerol have different surface tensions, and the exact values depend on concentration. Notice how the ink drops spread fastest from areas where the ink is densely concentrated. This tells us that the ink’s surface tension is lower than the glycerol’s. As a result, the glycerol’s higher surface tension tends to pull ink toward it. As the ink spreads and its concentration decreases relative to the glycerol, the ink-glycerol mixture’s surface tension increases. Since the difference between the surface tension of the mixture and the pure glycerol is not as large, the Marangoni force is reduced and the spreading slows. (Image credit: C. Kalelkar, source)

Un-Mixing a Flow

This video demonstrates one of my favorite effects: the reversibility of laminar flow. Intuition tells us that un-mixing two fluids is impossible, and, under most circumstances, that is true. But for very low Reynolds numbers, viscosity dominates the flow, and fluid particles will move due to only two effects: molecular diffusion and momentum diffusion. Molecular diffusion is an entirely random process, but it is also very slow. Momentum diffusion is the motion caused by the spinning inner cylinder dragging fluid with it. That motion, unlike most fluid motion, is exactly reversible, meaning that spinning the cylinder in reverse returns the dye to its original location (plus or minus the fuzziness caused by molecular diffusion).

Aside from being a neat demo, this illustrates one of the challenges faced by microscopic swimmers. In order to move through a viscous fluid, they must swim asymmetrically because exactly reversing their stroke will only move the fluid around them back to is original position. (Video credit: Univ. of New Mexico Physic and Astronomy)

Dye Droplet

A drop of fluorescent dye falling into quiescent water forms fantastical structures that are a mixture of vorticity, turbulence, and molecular diffusion. The horseshoe-like shape near the front of the drop is a typical shape for two fluids strained by moving past one another. The main section of the drop billows outward like a parachute, but the turbulence of its wake stretches the dye into fine threads that quickly disperse in the water. (Photo credit: D. Quinn et al.)

Reversing a Flow

The reversibility of laminar mixing often comes as a surprise to observers accustomed to the experience of being unable to separate two fluids after they’ve been combined. As you can see above, however, inserting dye into a highly viscous liquid and then mixing it by turning the inner of two concentric cylinders can be undone simply by turning the cylinder backwards. This works because of the highly viscous nature of Stokes flow: the Reynolds number is much less than 1, meaning that viscosity’s effects dominate. In this situation, fluid motion is caused only by molecular diffusion and by momentum diffusion. The former is random but slow, and the latter is exactly reversible. Reversing the rotation of the fluid undoes the momentum diffusion and any distortion remaining is due to molecular diffusion of the dye.

Testing Flames in Space

In microgravity, flames behave very differently than on earth due to a lack of buoyant forces. On earth, a flame can continue burning because, as the warm air around it rises, cooler air gets entrained, drawing fresh oxygen to the flame. In microgravity, both the heat from the flame and the oxygen it needs to burn move only by molecular diffusion, the random motion of molecules, or the background environmental flow (air circulation on the ISS, for example). This video shows a test of the Flame Extinguishment Experiment (FLEX) currently flying onboard the ISS. A fuel droplet is ignited, burns in a symmetric sphere and then eventually extinguishes either due to a lack of fuel or a lack of oxygen. Check out this NASA press release for more, including great quotes like this:

“As a Princeton undergrad, I saw in a graduate course the conservation equations of combustion and realized that those equations were complex enough to occupy me for the rest of my life; they contained so much interesting physics.” – Forman Williams

Molecular Diffusion

This video explains molecular diffusion with demonstrations in gases and liquids. Molecular diffusion is an important process in all fluids and will occur in laminar, turbulent, or quiescent fluids. Diffusion occurs more quickly in heated fluids because molecules move more energetically at higher temperatures. (via robertlovespi)

Un-Mixing a Fluid Demo

Not only is this demonstration one of my favorites, it’s a reader favorite, too. Even though I posted it nearly a year ago, I’ve had it resubmitted over and over. Here’s what I originally wrote:

Laminar flow (as opposed to turbulence) has the interesting property of reversibility. In this video, physicists demonstrate how flow between concentric cylinders can be reversed such that the initial fluid state is obtained (to within the limits of molecular diffusion, of course!)

For more examples, see the first half of this video.

The results of those videos might be surprising, but they highlight the difference between laminar flow and turbulence. In laminar flow, the motion of the dye is caused by molecular diffusion and momentum diffusion, the latter of which is exactly reversible. In turbulence, much of the fluid motion is tied up in momentum convection, which is irreversible. This is why you can “unstir” the glycerin but not the milk in your coffee.