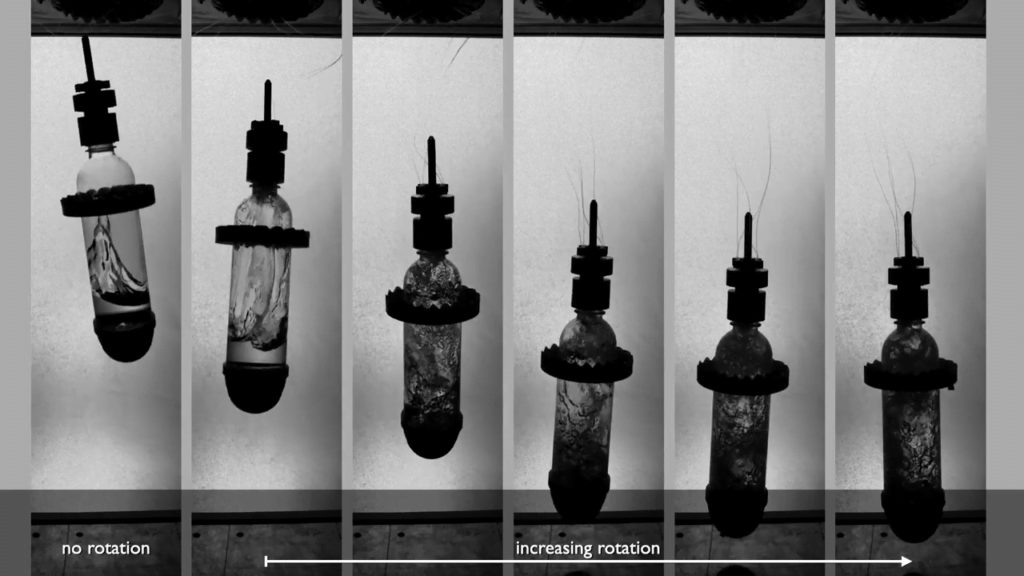

Drop a ball that’s partially filled with water and it may or may not bounce. Why the difference? It all comes down to where the water is before impact. The more distributed the water is along the walls, the less likely a container will bounce. Researchers found they could control the bounce by spinning the bottles before they dropped. Centrifugal force flings the water all over the walls of the spinning bottle, and, when impact happens, the water concentrates into a central jet. For the spinning bottles, that jet is wide, messy, and swirling; it breaks up quickly, expending energy that could otherwise go into a bounce. In effect, the spinning bottle’s jet forms quickly enough to “stomp” the rebound. (Video and image credit: A. Martinez et al.; research credit: K. Andrade et al.)

Tag: swirling

The Beauty of Flames

The flickering yellow and orange flames most of us are used to thinking of are rather different from the flames researchers study. In this video, the Beauty of Science team offers a short primer on different flame shapes studied in combustion, including laminar, swirling, and jet flames. Each has its own distinctive character and may be advantageous or not, depending on the application for the flame. A laminar flame, for example, is steady, which might make it a good choice for something like a Bunsen burner, where consistency is needed. Whereas a turbulent flame is better capable of mixing fuel and oxidizer, which is key in applications like rocket engines, where that mixing can be a limiting factor in the engine’s efficiency. (Image and video credit: Beauty of Science)

Swirling the Wrong Way

When you swirl wine, you create a rotating wave that travels in the direction that you’re moving the glass. You would expect that anything floating atop that fluid would travel in the same direction of rotation. But it turns out, for a large, thin raft floating atop the rotating fluid, that’s not the case.

Above you can see a swirling container, rotating counter-clockwise, with a raft of foam. This is from a timelapse where only one photo is taken per rotation, so that it’s easier to see how the foam is rotating relative to the container. And, once enough foam covers the surface, it starts rotating in a clockwise direction – opposite the container! It works for more than foam, too. The researchers show that the same holds for powders or beads. The key to the counter-rotation is that the raft needs to be coherent; it has to be able to transmit friction and internal stress among its constituents. Otherwise, the raft will just drift along with the swirling wave. (Image and research credit: F. Moisy et al., source, arXiv; via Improbable Research; submitted by David H. and Kam-Yung Soh)

Salinity Near the Amazon

This numerical simulation shows the variation of salinity in the Atlantic Ocean near the mouth of the Amazon River over the course of 36 months. The turbulent mixing of the fresh river water and salty ocean shifts with the ebb and flooding of the river. Salt content causes variations in ocean water density, which can strongly affect mixing and transport properties between different depths in the ocean due to buoyancy. Understanding this kind of flow helps predict climate forecasts, rain predictions, ice melting and much more. (Video credit: Mercator Ocean)

Swirling Fluids

In this video, researchers investigate swirling fluids by studying the shapes of the free surface between air and the liquid. As parameters like the diameter of the glass, initial (unperturbed) height of the liquid, and angular velocity of the rotation change, the surface of the liquid displays different modal behaviors, seen in the photos on the lower left of the video. By non-dimensionalizing the physical parameters of the system (students: think Buckingham pi theorem), they are able to replicate the shape of the free surface by matching a Froude number and dimensionless depth and offset. Such similitude between fluids under different conditions is key to understanding the underlying physics. (Video credit: M. Reclari et al; submitted by co-author M. Farhat)