Under a macro lens, even a petri dish worth of fluids comes vividly to life. Here, artist Scott Portingale explores crystallization, Marangoni effects, and other phenomena alongside a haunting soundtrack from musician Gorkem Sen. Enjoy! (Image and video credit: S. Portingale et al.)

Tag: surface tension

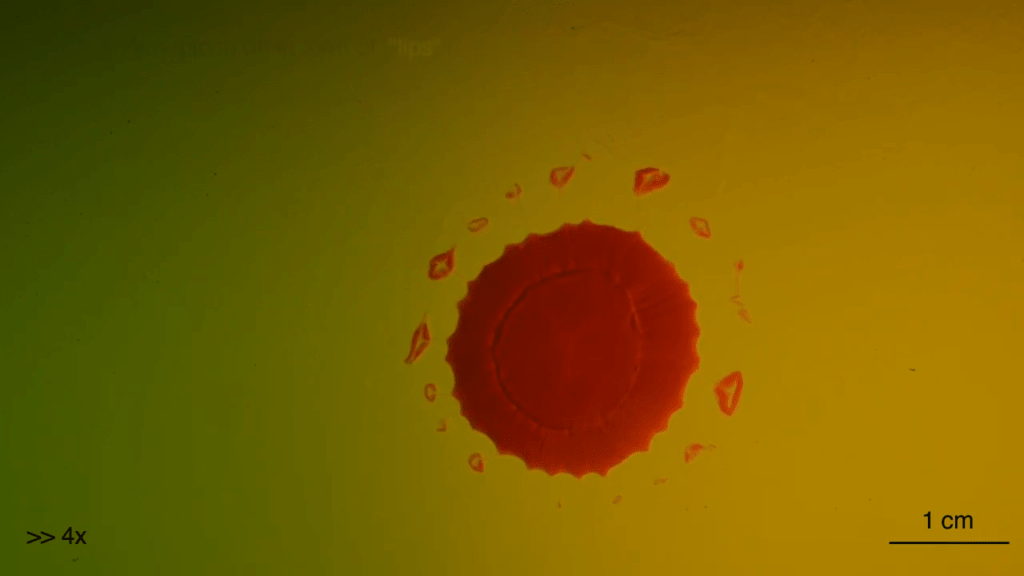

Marangoni Blossoms

When surface tension varies along an interface, fluids move from regions of low surface tension to higher surface tension, a behavior known as the Marangoni effect. Here, a drop of (dyed) water is placed on glycerol. The two fluids are miscible, but water has much a lower viscosity and density yet a higher surface tension. The drop’s interface quickly becomes unstable; viscous fingers form along the edge as the less viscous water pushes into the more viscous glycerol. Eventually, the surface-tension-driven Marangoni flow breaks those fingers off into lip-like daughter drops. The researchers also show how the interplay between viscosity and surface tension affects the size of fingers that form by varying the water/glycerol concentration. (Image and video credit: A. Hooshanginejad et al.)

Tweaking Coalescence

When a drop settles gently against a pool of the same liquid, it will coalesce. The process is not always a complete one, though; sometimes a smaller droplet breaks away and remains behind (to eventually do its own settling and coalescence). When this happens, it’s known as partial coalescence.

Here, researchers investigate ways to tune partial coalescence, specifically to produce more than a single droplet. To do so, they add surfactants to the oil layer surrounding their water droplet. The surfactants make the rebounding column of water skinnier, which triggers the Rayleigh-Plateau instability that’s necessary to break the column into more than one droplet. (Image and video credit: T. Dong and P. Angeli)

Playing With Water in 2D Containers

Once again Steve Mould is putting his prototyping skills to use to work out what goes on inside tricky containers. Here he looks at a “magic” wizard’s cup where — like the assassin’s teapot — cleverly placed holes in the side of the cup can block or allow air’s escape. In the wizard’s cup this lets the wizard refill the cup at will.

He also takes a look at how draining works, using tracer particles and a video editing effect that “echoes” previous frames in a video. For the tracer particles, this algorithm effectively visualizes pathlines in the flow. Areas with faster-moving fluid have longer pathlines that are closer together, whereas slow-moving regions have short pathlines. (Video credit: S. Mould)

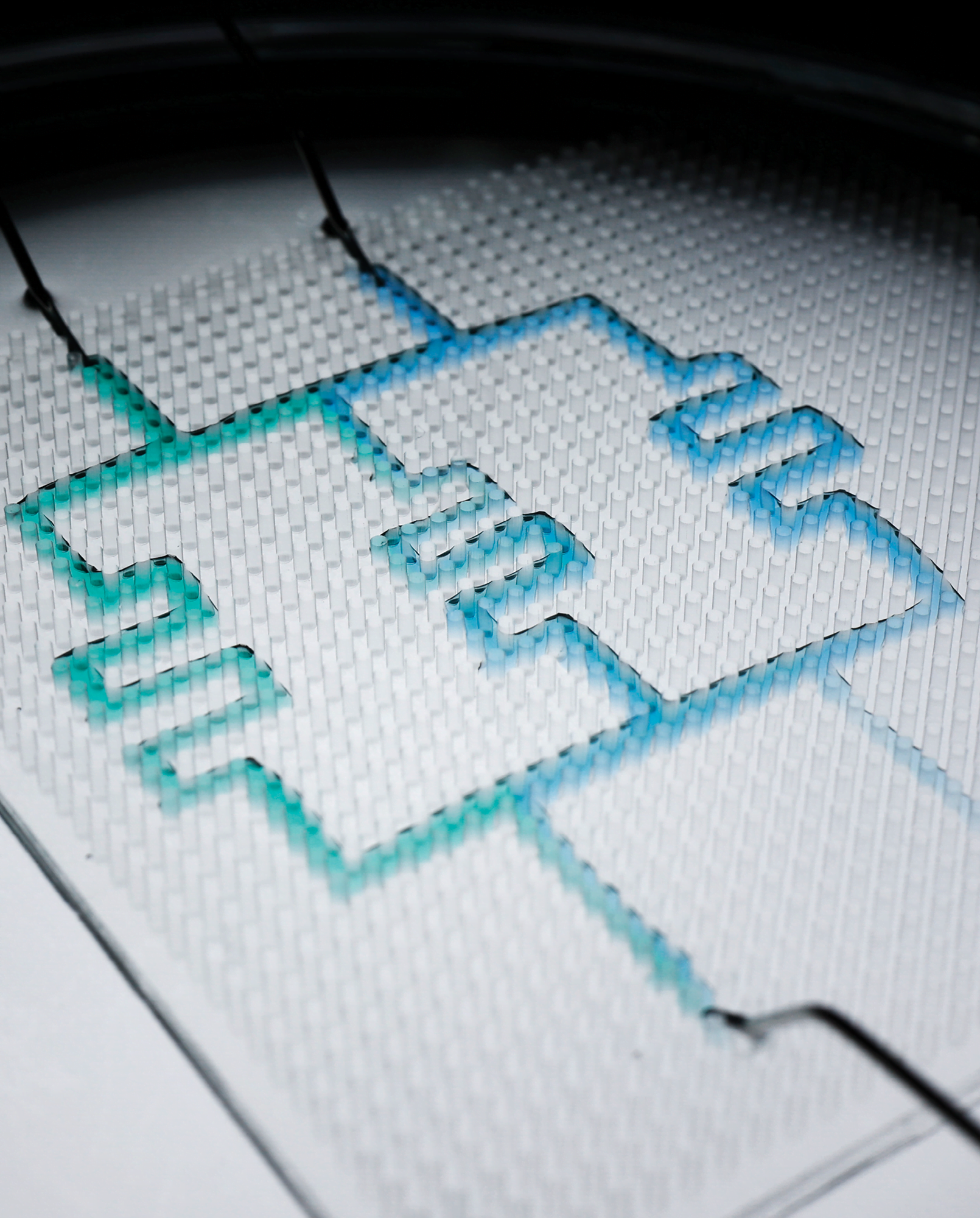

Making Reconfigurable Liquid Circuits

Microfluidic circuits are key to “labs on a chip” used in medical diagnostics, inkjet printing, and basic research. Typically, channels in these circuits are printed or etched onto solid surfaces, making it difficult to reconfigure them. A group in China developed an alternative design, inspired by reconfigurable toys like Lego blocks. Their set-up, shown above, uses a pillared surface immersed in oil. To create the channels, they pipette water — one droplet at a time — into the space between pillars. The combination of oil and pillars traps the drop. With multiple drops linked together, they get channels, like the ones above that mix two fluids. When the time comes to reconfigure the channels, they just pipette the water out and cut the channel with a sheet of coated paper. (Image and research credit: Y. Zeng et al.; via Physics Today)

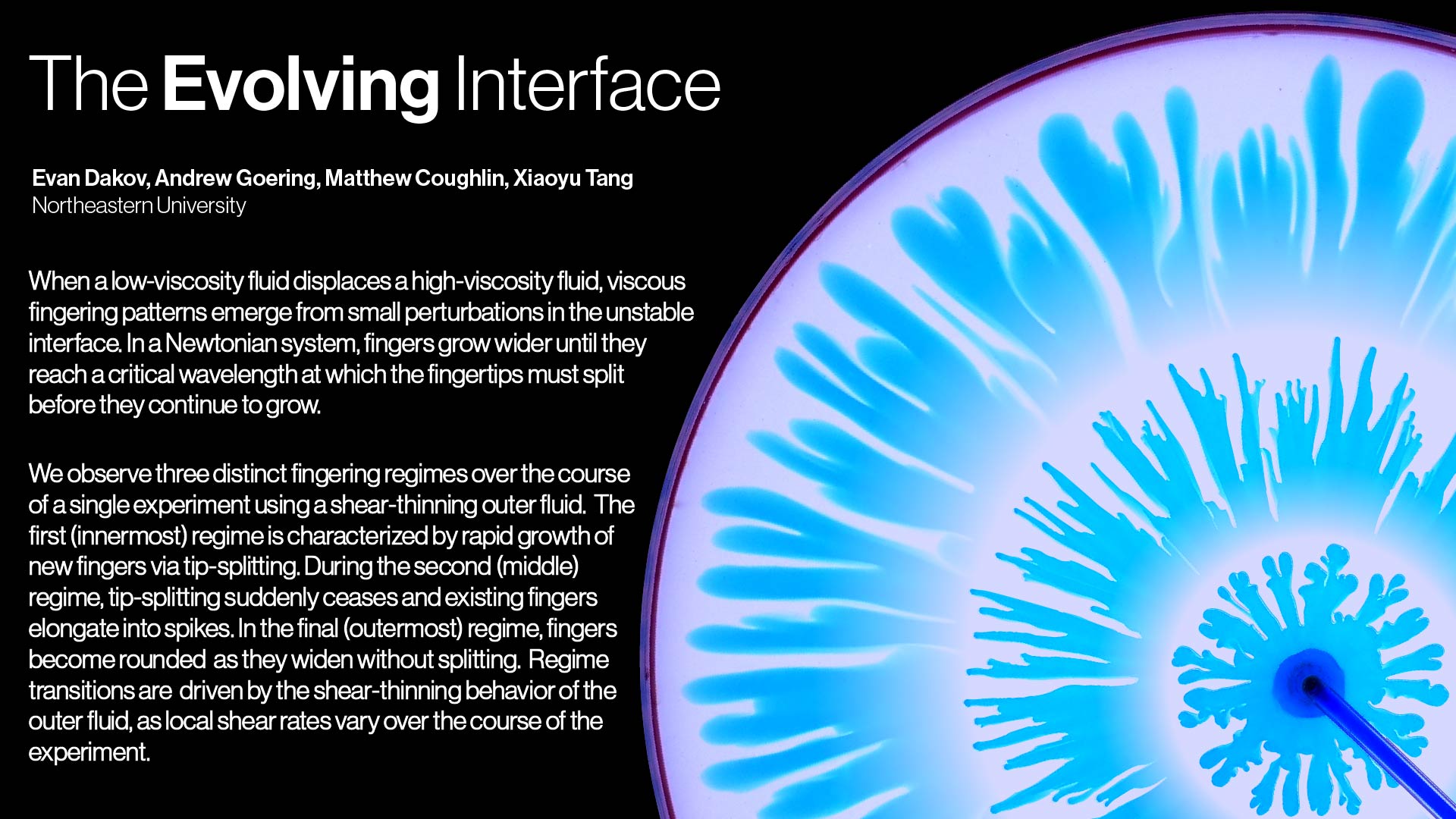

Evolving Fingers

If you sandwich a viscous fluid between two plates and inject a less viscous fluid, you’ll get viscous fingers that spread and split as they grow. This research poster depicts that situation with a slight twist: the viscous fluid (transparent in the image) is shear-thinning. That means its viscosity drops when it’s deformed. In this situation, the fingers formed by the injected (blue) fluid start out the way we’d expect: splitting as they grow (inner portion of the composite image). But then, the tip-splitting stops and the fingers instead elongate into spikes (middle ring). Eventually, as the outer fluid’s viscosity drops further, the fingers round out and spread without splitting (outer arc of the image). (Image credit: E. Dakov et al.; via GoSM)

“Color Show”

Brightly colored paints and inks mix and flow in artist Roman De Giuli’s “Color Show.” De Giuli typically creates this fluid art in thin layers atop paper. He’s a master of the form, manipulating surface tension gradients to create streaming flows, dendritic patterns, and feathery wisps. If this kind of art is your jam, he offers an app full of live wallpapers* for Android phones. See more of his work on his website and on Instagram. (Video and image credit: R. De Giuli)

*Not sponsored, I just like his art!

Dendritic Painting Physics

In the art of Akiko Nakayama, colors branch and split in a tree-like pattern. In studying the process, researchers found the physics intersected art, soft matter mechanics, and statistical physics. In dendritic painting, the process starts with an underlying layer of acrylic paint, diluted with water. Atop this wet layer, you place a drop of acrylic ink mixed with isopropyl alcohol.

The combination of both layers is key. The alcohol-acrylic drop on a Newtonian substrate will show spreading, driven by Marangoni forces, but no branching. It’s the slightly shear-thinning nature of the diluted acrylic paint substrate that allows dendrites to form. As the overlying drop expands, it shears the underlayer, changing its viscosity and allowing the branches to form. You can see video of the process here. (Image credit: A. Nakayama; research credit: S. Chan and E. Fried; via Physics World)

Lasers and Soap Films

Soap films are a great system for visualizing fluid flows. Researchers use them to look at flags, fish schooling and drafting, and even wind turbines. In this work, researchers explore the soap film’s reaction to lasers. When surfactant concentrations in the soap film are low, laser pulses create shock waves (above) in the film that resemble those seen in aerodynamics. The laser raises the temperature at its point of impact, lowering the local surface tension. That temperature difference triggers a Marangoni flow that draws the heated fluid outward. The low surfactant concentration gives the soap film relatively high elasticity, and that allows the shock waves to form.

In contrast, a soap film with a high concentration of surfactants has relatively little elasticity. In these films (below), the laser creates a mark that stays visible on the flowing soap film. This “engraving” technique could be used to visualize flow in the soap film without using tracer particles. (Image and research credit: Y. Zhao and H. Xu)

When surfactant concentrations are high, a laser pulse “engraves” spots onto a flowing soap film. Shown in terms of interference (left) and Schlieren (right) imaging.

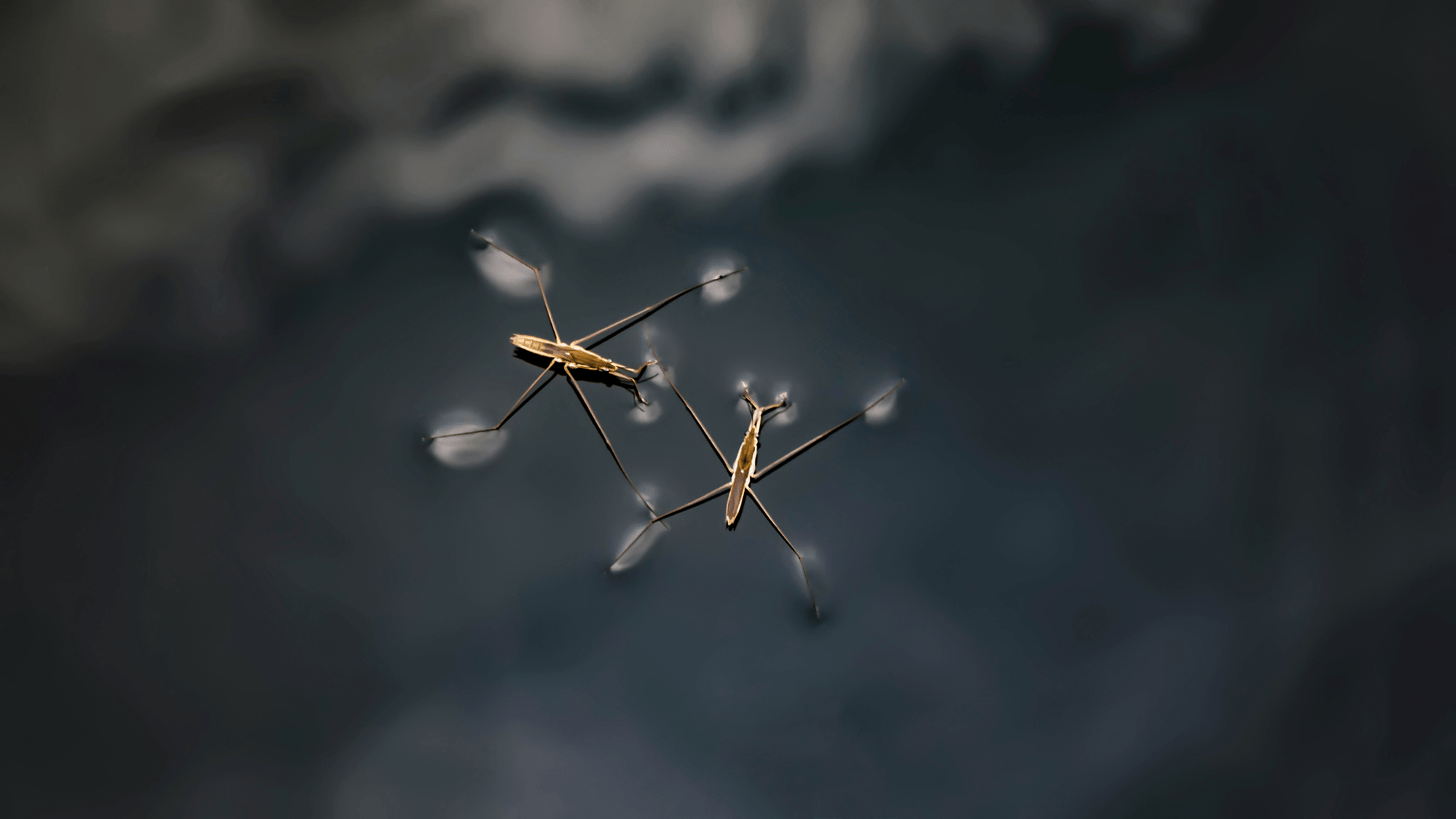

Surviving Rainfall

Water striders spend their lives at the air-water boundary, skittering along this interfacial world. But what happens when falling rain destroys their flat existence? That’s the question that motivated today’s research study, which looks water striders subjected to artificial rain.

Although the water drops themselves are far heavier than the insects, the water doesn’t strike hard enough to injure the insects. Neither a direct impact nor the forces from a neighboring impact, the researchers found, were enough to pose a problem for the water strider’s exoskeleton. Instead, they’re more likely to get flung or submerged, as follows:

The initial impact of a raindrop creates a large crater. Depending on the position of the insect relative to the point of impact, this may fling the insect away or pull it down into the cavity. When the drop hits, it creates a big crater in the water’s surface. Insects to the outside of the splash get flung outward, while those closer to the point of impact ride the crater wall downward. As the crater collapses, it forms a thick jet that pushes nearby water striders up with it.

As the initial cavity collapses, it creates a large jet that can push the strider into the air. As that initial jet collapses, it forms a second crater, which — being smaller and narrower — collapses much faster than the first one. That action, researchers found, often submerges a water strider caught in the crater.

The first jet’s collapse creates a second crater, and it’s this one that tends to trap and submerge the water strider underwater. Fortunately for the insect, their water-repellent nature means they’re covered in a thin bubble of air that lets them survive several minutes underwater. That’s time enough for the water strider to rescue itself. (Image credit: top – H. Wang, animations – D. Watson et al.; research credit: D. Watson et al.; via APS Physics)