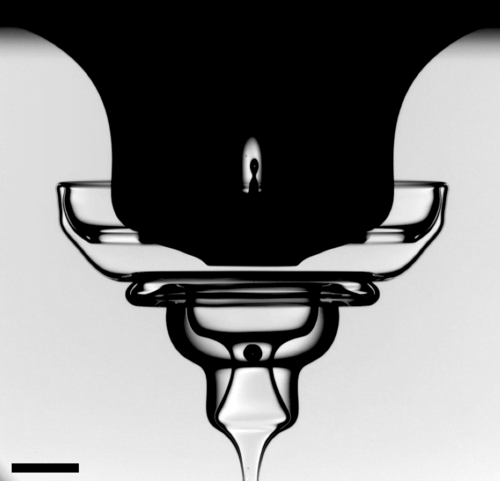

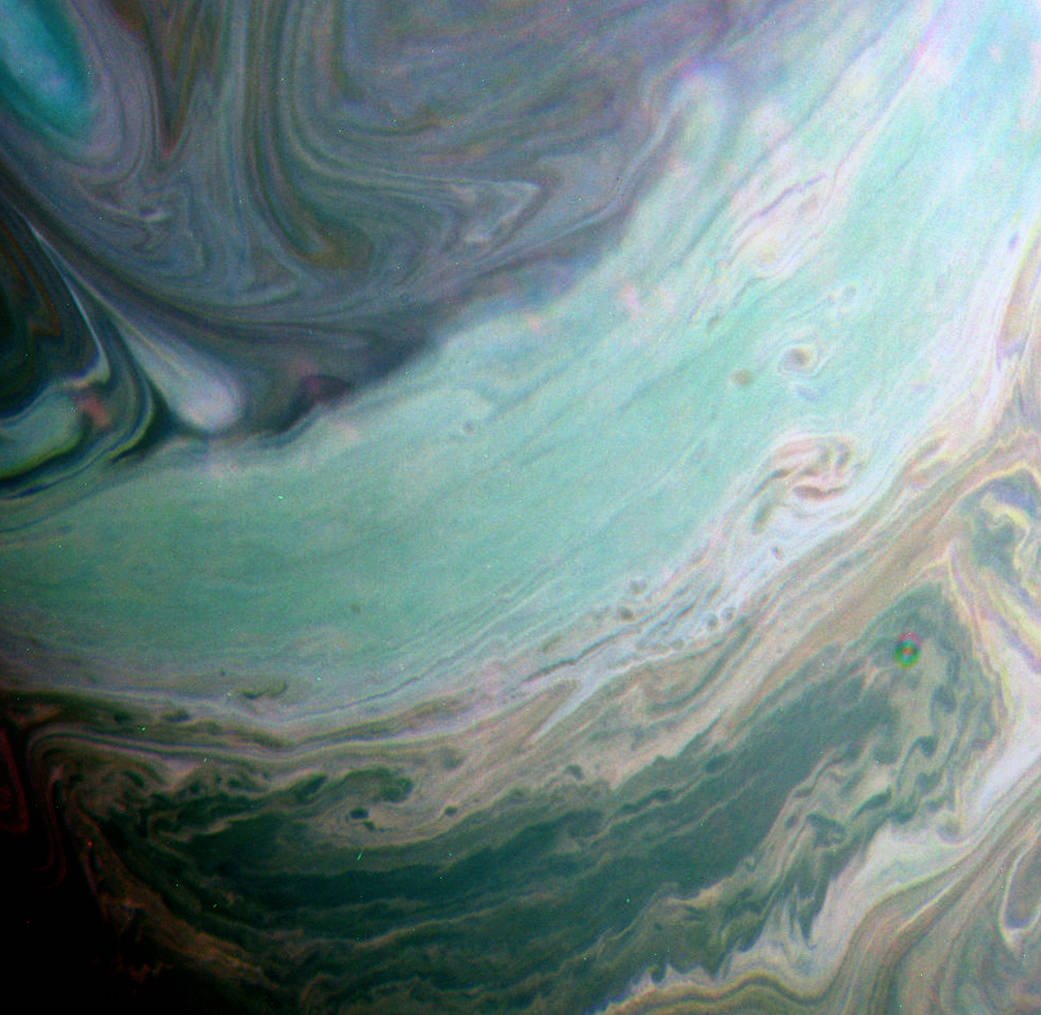

When a ship moves through water, it leaves a distinctive V-shaped wake behind it. In the nineteenth century, Lord Kelvin made some of the earliest theoretical studies of this phenomenon, calculating that the arms of the V should have an angle of about 39 degrees, known as the Kelvin angle. But that theoretical result doesn’t always hold in practice.

More recently, researchers calculated and experimentally verified an extension to Kelvin’s theory, one which accounts for what’s going on below the water. They found that any shear in the currents below the surface can strongly affect the shape of a boat’s wake, altering angles and creating asymmetry between the two sides. The results have practical consequences, too: they help predict the wave resistance ships will encounter when traversing areas with substantial subsurface shear, like near the mouths of river deltas. (Image credit: M. Adams; research credit: B. Smeltzer et al.; submitted by clogwog)