Sprites, or red sprites, are high-altitude electrical discharges in the atmosphere. Although sometimes called upper-atmospheric lightning, sprites are a cold plasma phenomenon. They often occur in clusters, as in this photo by Angel An, which won in the Skyscapes category of the 2023 Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition. Sprites, which last only a millisecond or so, take place during intense thunderstorms, but, unlike our more familiar lightning, sprites move upward from the storm toward the ionosphere. They can occur on Venus, Saturn, and Jupiter as well, although sprites have only been observed directly on Earth and Jupiter. (Image credit: A. An; via Colossal)

Tag: plasma

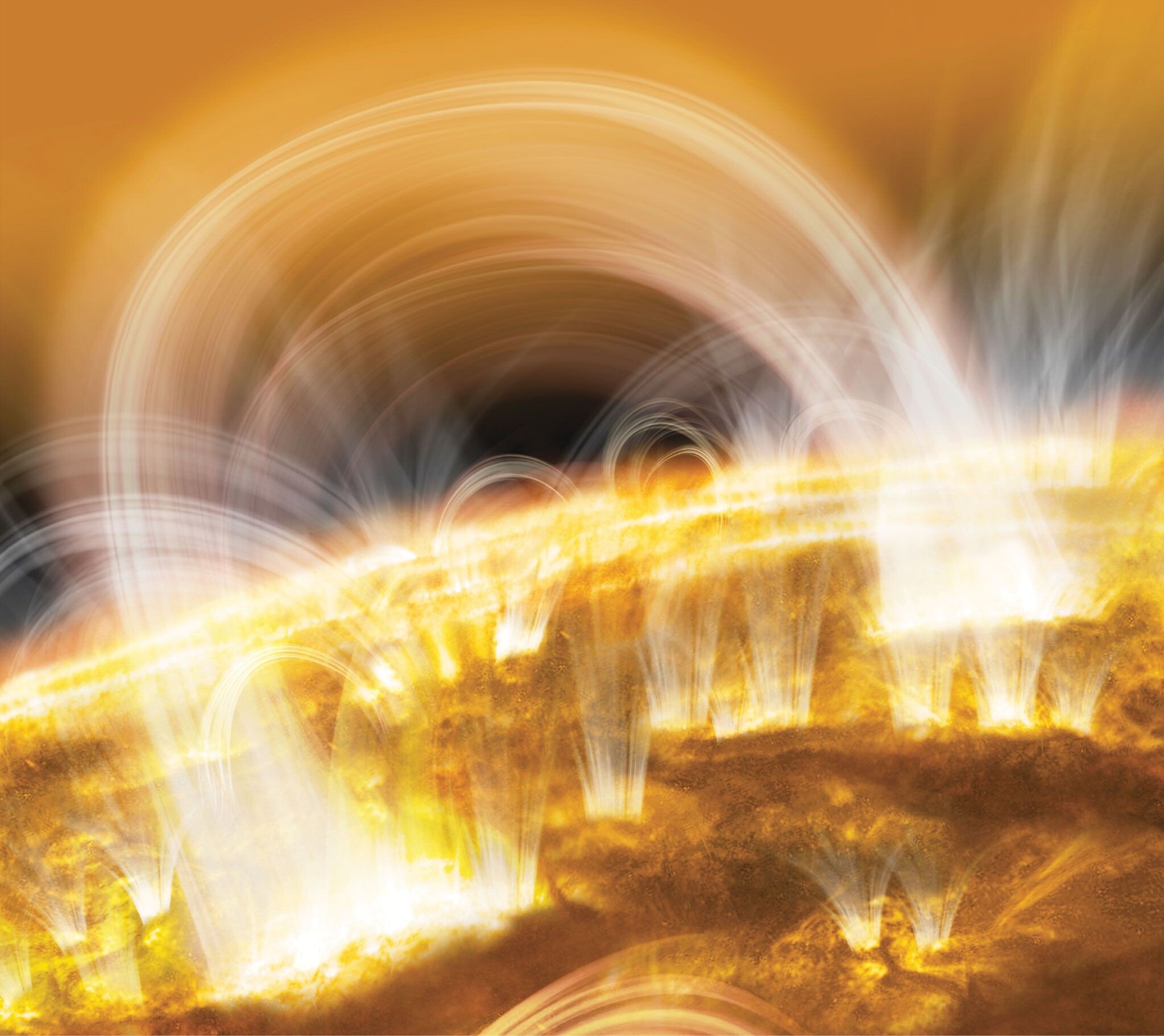

Solar Coronal Heating

Our Sun‘s visible surface, the photosphere, is about 5800 Kelvin, but the temperature of the wispy corona is far hotter, reaching a million Kelvin in some places. Why the corona is so hot remains something of a mystery. Scientists have theorized multiple culprits for the extreme temperatures found in the corona, but the full details of the phenomenon are still unclear.

Recent solar missions and observations are increasingly identifying small but widespread solar activities, like the nanoflares shown above. Unlike the monstrous coronal loops researchers focused on previously, these flares are tiny and occur in regions without discernible solar flare activity. The nanoflares are brief but they can reach temperatures above a million Kelvin. Since nano- and even picoflares have been observed across the full Sun, they likely play a significant role in the overall picture of coronal heating. (Image credit: ISAS/JAXA; see also L. Sigalotti and F. Cruz)

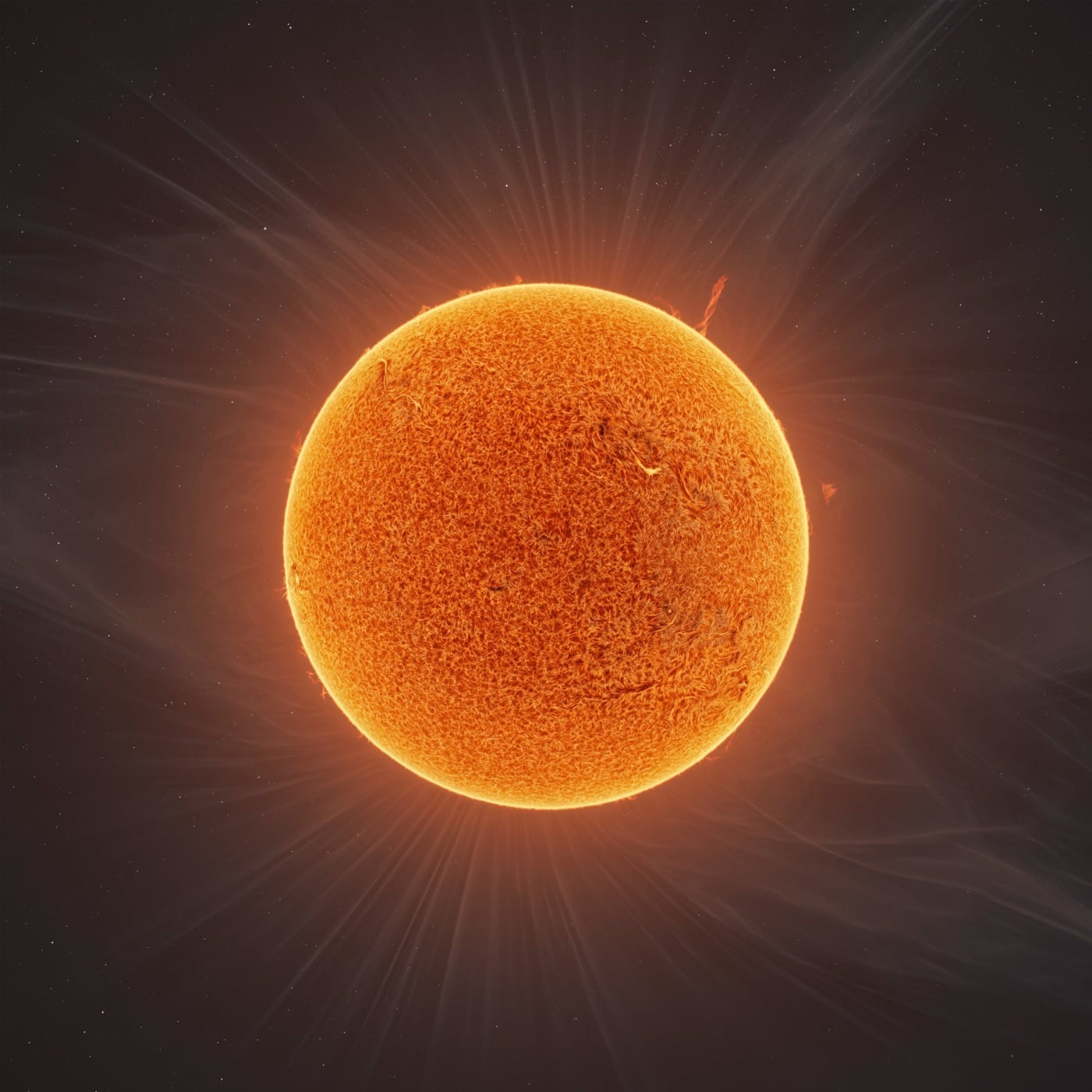

“Fusion of Helios”

Built from approximately 90,000 individual images, “Fusion of Helios” reveals the wisp-like corona of our Sun. Astrophotographers Andrew McCarthy and Jason Guenzel joined forces to combine eclipse images with data from NASA to build this fusion of art and science. Jets of plasma, known as spicules, dot the sun’s surface, and a towering tornado of plasma shoots off one side. For scale, that vortex stretches as far as 14 Earths stacked atop one another. (Image credit: A. McCarthy and J. Guenzel; via Colossal)

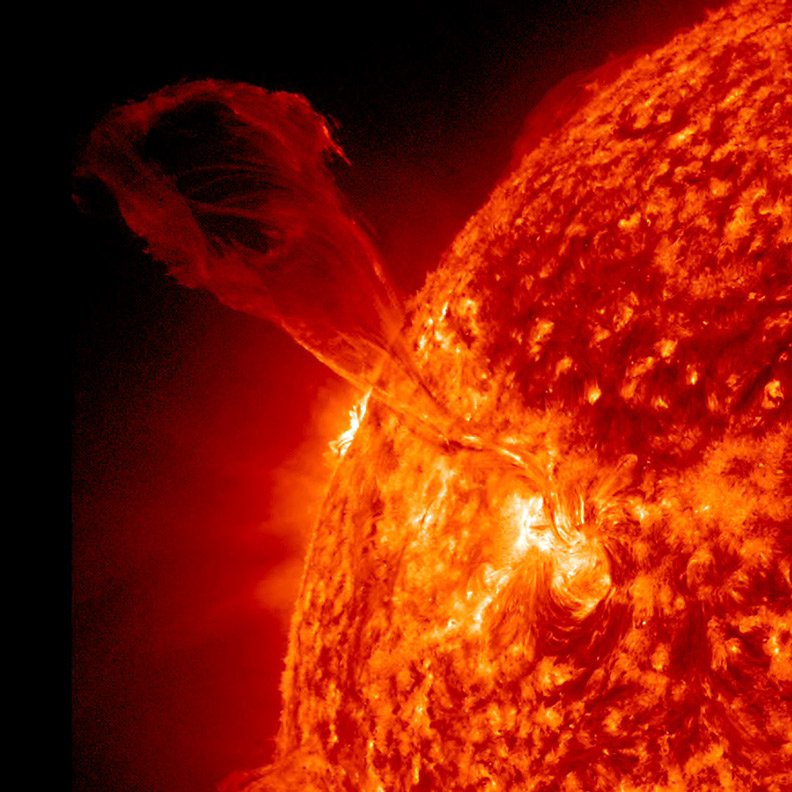

Escaping the Sun

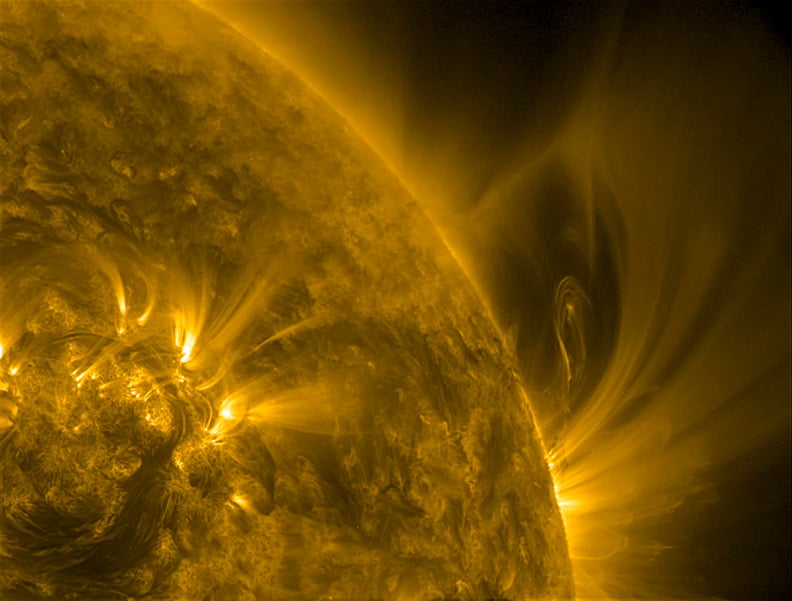

One enduring mystery of the solar wind — a stream of high-energy particles expelled from the sun — is how the particles get accelerated in the first place. The sun frequently belches out spurts of plasma, but without further momentum, that material simply falls back to the sun’s surface under the star’s gravity. Mechanisms like shock waves can further accelerate particles that are already moving quickly, but they cannot explain how the particles get going in the first place.

A recent study used supercomputers to tackle this challenging problem in turbulent plasma physics. Each simulation tracked nearly 200 billion particles, requiring tens of thousands of processors. The results showed that turbulence itself provides the necessary initial acceleration and serves as the first step to getting particles moving fast enough to escape the sun. (Image credit: NASA SDO; research credit: L. Comisso and L. Sironi; via Physics World)

Coronal Heating

Compared to its interior, the surface of our sun is a cool 6,000 degrees Celsius. But beyond the surface, the sun’s corona heats up dramatically through interactions between plasma and strong magnetic fields. The exact mechanisms of this interaction have been mostly theoretical thus far, but a recent laboratory experiment has validated a part of that theory.

One explanation for coronal heating posits that the strong magnetic fields can accelerate magnetohydrodynamic waves called Alfvén waves to speeds faster than sound, and that at this crossover point, changes occur in the waves’ behavior. Using liquid rubidium, researchers were able to observe this crossover under laboratory conditions, confirming that the Alfvén waves change at the speed of sound in exactly the manner predicted by theory. (Image credit: NASA SDO; research credit: F. Stefani et al.; via Physics World)

“One Month of Sun”

Get lost in the beauty of our star with Seán Doran‘s film “One Month of Sun”. Constructed from more than 78,000 NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory images, the video shows solar activity from August 2014, particularly the golden coronal loops that burst forth from the sun’s visible surface. These bursts of hot plasma follow the sun’s magnetic field lines, often emerging from sunspots. (Image and video credit: S. Doran, using NASA SDO data; via Colossal)

Space Hurricanes

Researchers have observed their first “space hurricane” – a 1,000-km-wide vortex of plasma – in Earth’s upper atmosphere. Like conventional hurricanes, this storm featured precipitation (of electrons rather than rain), a calm eye at its center, and several spiral arms. Based on the group’s model, interactions between the solar wind and Earth’s magnetic fields drive the storm. Interestingly, the storm they observed occurred during a period of low solar and geomagnetic activity, which suggests that such space hurricanes could be frequent, both on Earth and in the upper atmospheres of other planets. (Image credit: Q. Zhang; research credit: Q. Zhang et al.; via Physics World)

Jovian Auroras

Like Earth, Jupiter is home to polar auroras that light the sky as charged particles interact with the planet’s magnetosphere. A recent paper identifies interesting features in the aurora that appear similar to expanding vortex rings (see inset below). Although the researchers cannot yet identify the origin of the rings, they hypothesize that the process begins at the far edges of Jupiter’s magnetosphere where it interacts with the incoming solar wind. One theory posits that shear flows and Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities where the magnetosphere and solar wind meet drive the phenomenon. (Image credit: Jupiter – NASA, ESA, and J. Nichols, aurora features – NASA/SWRI/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/V. Hue/G. R. Gladstone/B. Bonfond; research credit: V. Hue et al.; via Gizmodo)

Blue Jets

Blue jets are a mysterious form of lightning that shoots upward from intense thunderstorms. The image above comes from one of the first color videos of blue jets, taken by an astronaut aboard the International Space Station. Scientist think blue jets form during an electric breakdown between the positively-charged upper region of a cloud and the negative charge at its boundary. Once the discharge starts, it can shoot to the stratopause in less than a second, forming a glowing, blue, nitrogen-based plasma. (Image credit: ESA/NASA/DTU Space; via NASA Earth Observatory)

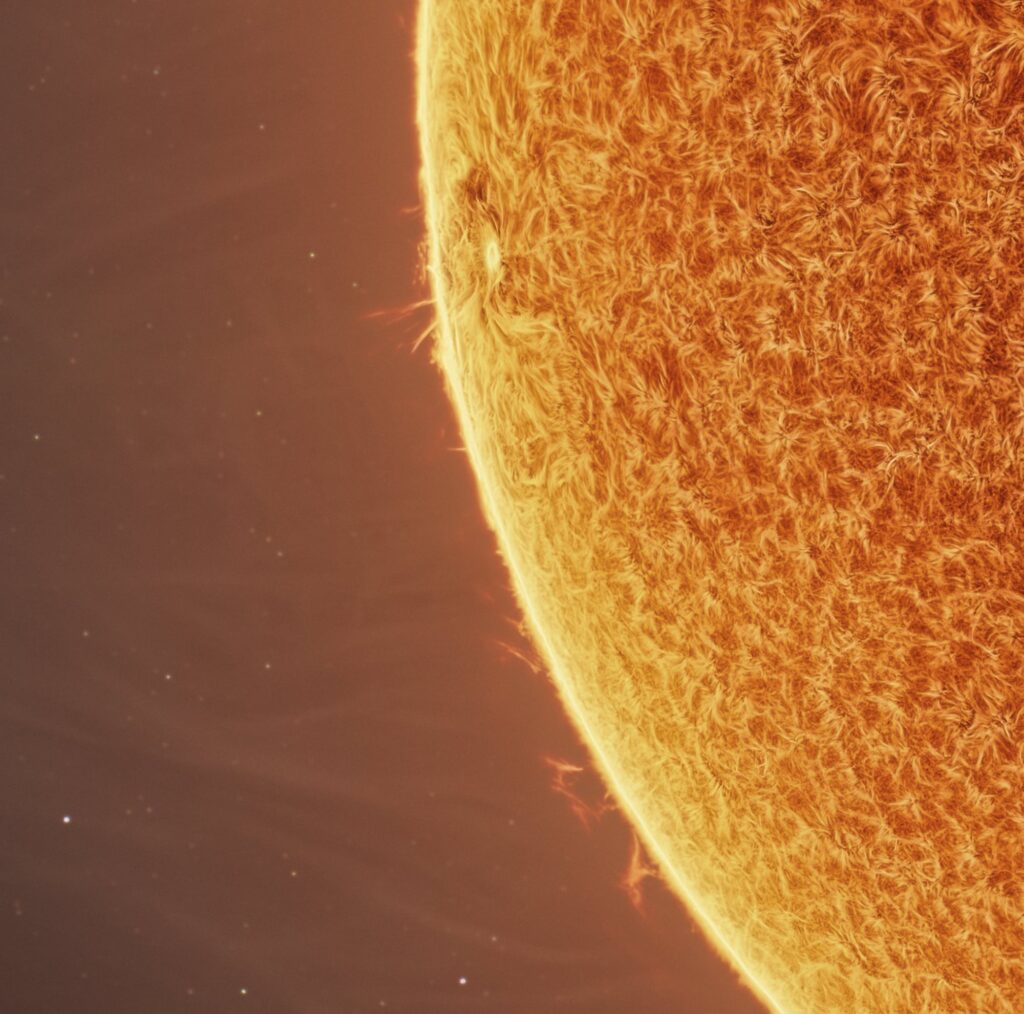

New Details on the Sun’s Surface

As part of its shakedown, the new Inouye Solar Telescope has captured the surface of the sun in stunning new detail. Seen here are some of the sun’s turbulent convection cells, each about the size of the state of Texas. Hot plasma rises in the center of each cell, cools, and then sinks near the dark edges. Also visible within these dark borders are bright spots thought to mark magnetic fields capable of channeling energy out into the corona. Researchers hope the new telescope will help them uncover the physics behind these processes. (Image and video credit: Inouye Solar Telescope)

Editor’s note: Like several other telescopes located in Hawai’i, the Inouye Solar Telescope was built against the wishes of many native Hawaiians. Although FYFD supports scientific progress, it is my personal belief that scientific advances should not come at the expense of indigenous populations. I strongly urge my scientific colleagues to listen to and work alongside those with concerns about future facilities.