Water is a decidedly weird substance. It’s densest above its freezing point; it has a slippery liquid-like layer on its solid form; and, in the right form, it can bend like a wire. So it’s not surprising that water demonstrates some odd behaviors when it’s confined inside a space so narrow it’s only one molecule thick.

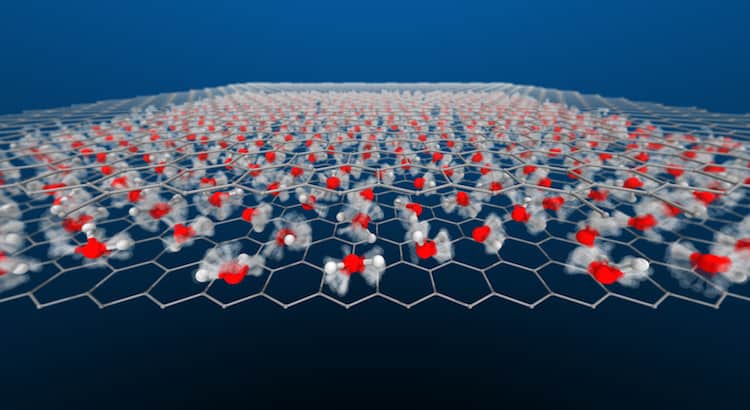

A new, simulation-based study finds that this nanoscale-confined water flows with a wide variety of behaviors, depending on the temperature and pressure. In some conditions, the water ceases to act molecularly, with hydrogen atoms flowing through a lattice of oxygen atoms. These superionic forms were thought only to exist in the extreme conditions of a gas giant’s interior, but these simulations suggest we can find them under far milder circumstances. (Image and research credit: V. Kapil et al.; via Physics World; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)