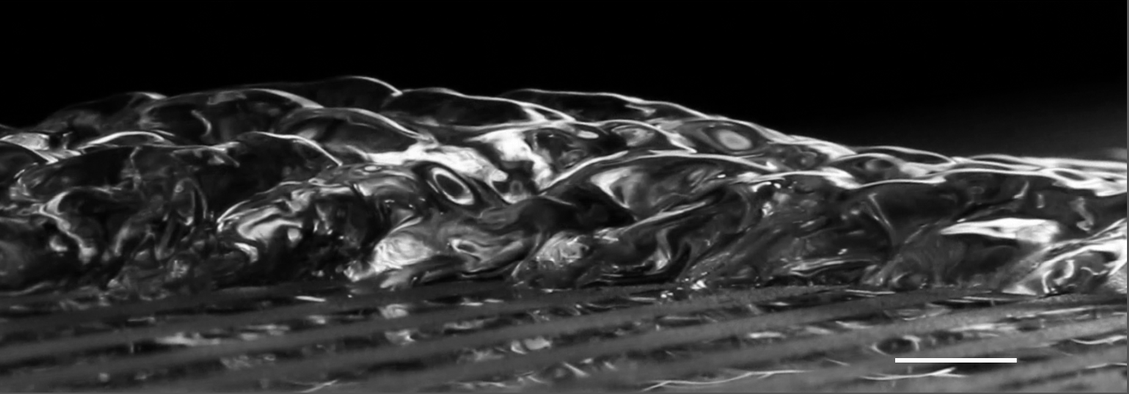

Longtime readers may recall seeing this little bubble-crowned anole previously. This species dives underwater to escape predators and will breathe and rebreathe a bubble of air for as much as 18 minutes before resurfacing. At the time of my original post, I speculated that the reptile’s hydrophobic skin might provide a large enough bubble surface area to provide some diffusion of fresh oxygen from the surrounding water.

Since then, there’s been at least one study of this anole rebreathing process. Researchers found that many anole species share this behavior, but aquatic species use it more regularly. They noted that the plastron — that flat, silvery bubble that’s spread over the lizard’s skin — helps hold the bigger, exhaled bubble in place and might facilitate a little of the diffusion I speculated about but the results are unclear on that last point. The authors note that it’s unlikely that the anoles could support their full metabolism through rebreathing and diffusion but that the plastron may yet support some rejuvenation of oxygen, which would help prolong anoles’ dives. (Image and research credit: C. Boccia et al.)