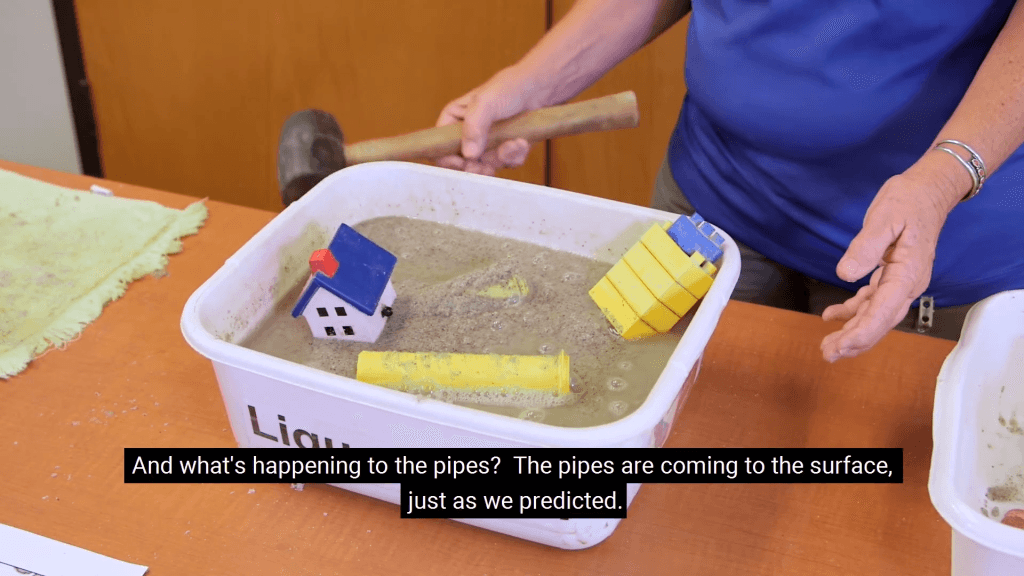

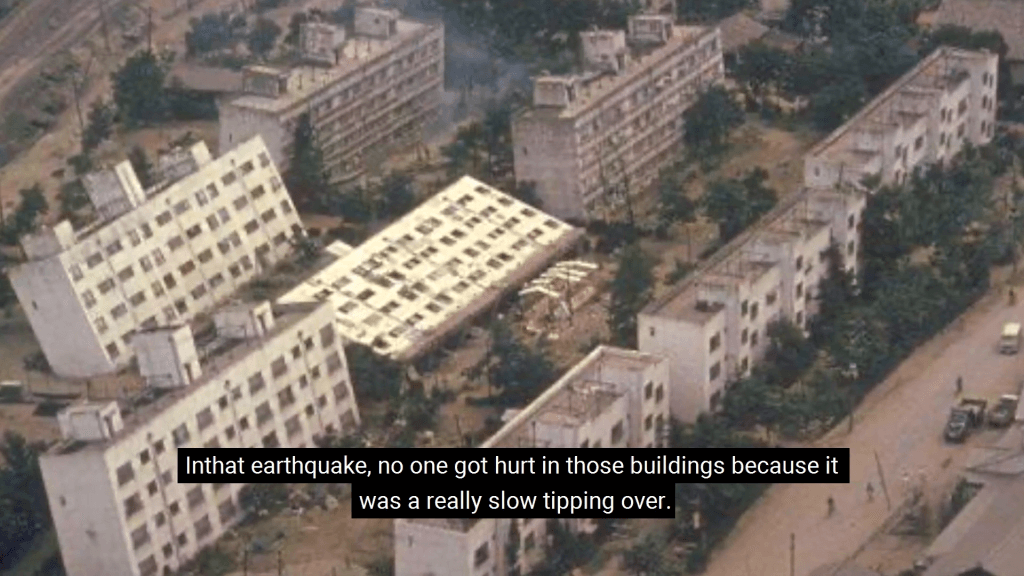

When a strong earthquake causes liquefaction, sand can intrude upward, leaving behind a feature that resembles an upside-down icicle. Known as a sand dike, researchers suspected that these intrusions could help us date ancient earthquakes. A new study shows how and why this is possible.

Using optically stimulated luminescence, researchers had already dated quartz in sand dikes and found that it appeared to be younger than the surrounding rock formations. But that information alone was not enough to tie the sand dike’s age to the earthquake that caused it.

The final puzzle piece fell into place when researchers showed that, during a sand dike’s formation, friction between sand grains could raise the temperature higher than 350 degrees Celsius. That temperature is high enough to effectively “reset” the age that luminescence dates the quartz to. Since the quartz likely wouldn’t have had another reset since the earthquake that put it in the sand dike, this means scientists can date the sand dikes themselves to determine when an earthquake occurred. (Image credit: Northisle/Wikimedia Commons; research credit: A. Tyagi et al.; via Eos)