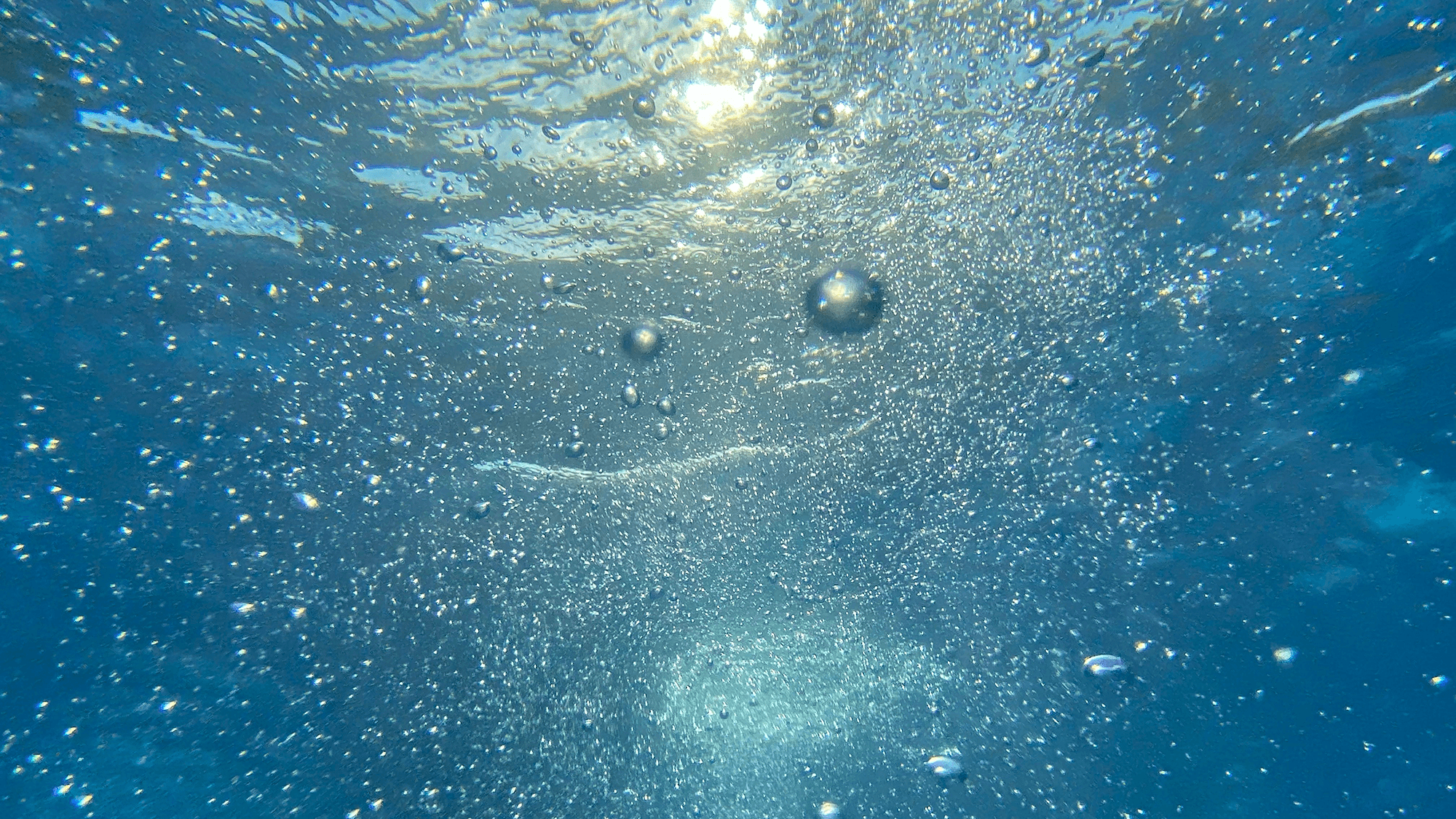

As humanity pumps carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, the ocean absorbs about a quarter of it. This exchange happens largely through bubbles created by breaking waves. When waves grow large enough to break, their crests curl over and crash down, trapping air beneath them. The turbulence of the upper ocean can push these buoyant bubbles meters under the surface, where the gases inside them dissolve into the surrounding water. This is how the ocean gets the oxygen used by marine animals, but it’s also how it gathers up carbon dioxide.

Current climate models often approximate this process using only the wind speed, but a recent study took matters a step further by modeling wave breaking and bubble generation, too. While they found a global carbon uptake that was similar to existing models, the researchers found their breaking wave model showed more variability in where carbon gets stored. For example, more carbon got absorbed in the southern hemisphere, where oceans are consistently rougher, than in the northern hemisphere, where large landmasses shelter the oceans. (Image credit: J. Kernwein; research credit: P. Rustogi et al.; via Eos)