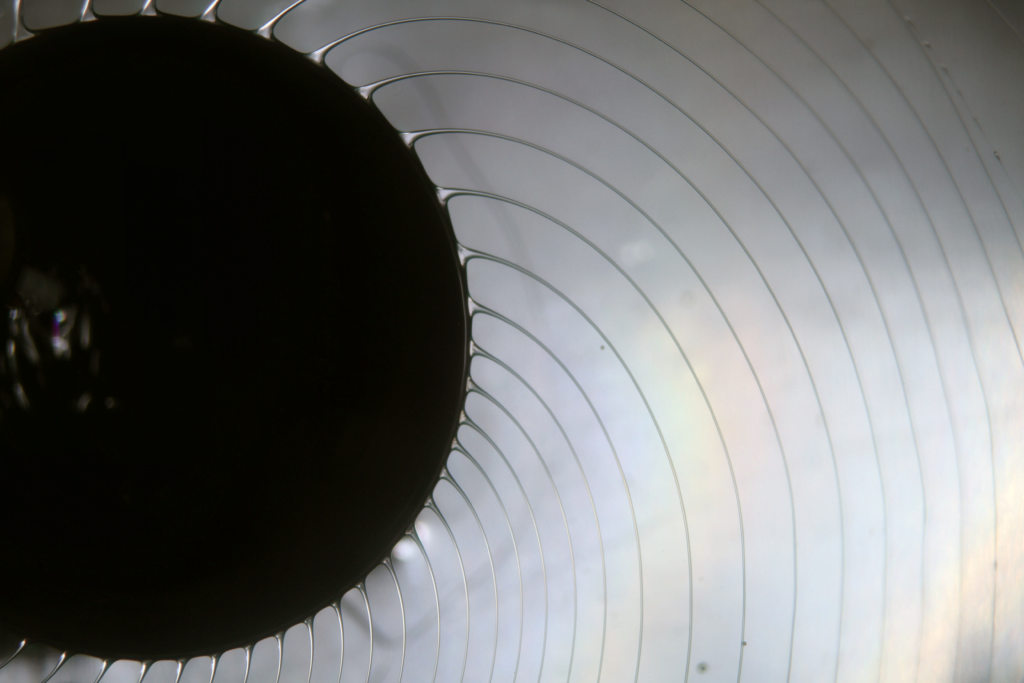

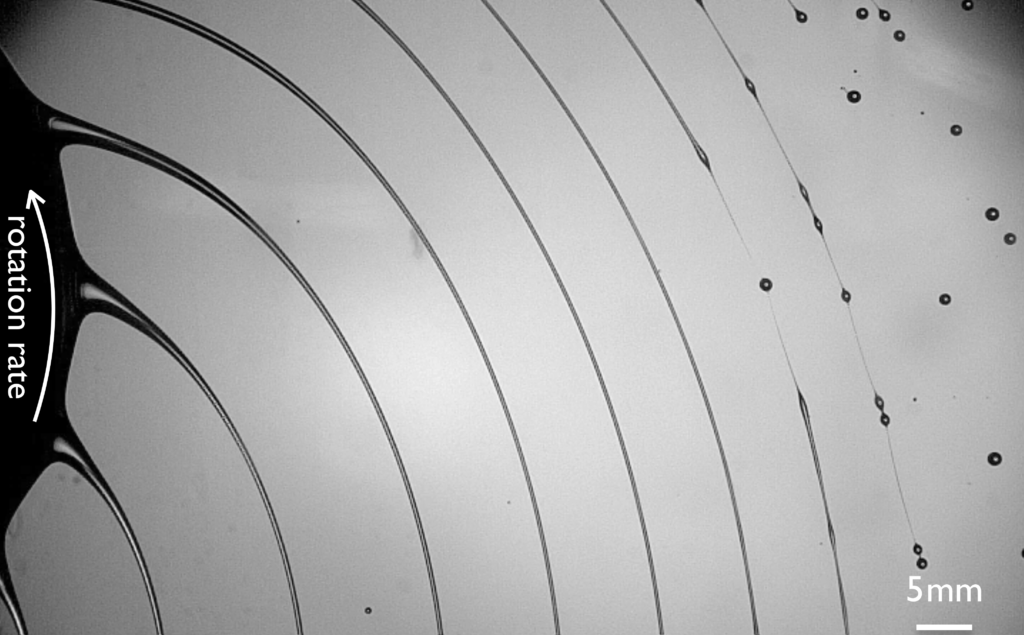

Rotational motion is a great way to break up liquids, as anyone who’s watched a dog shake itself dry can attest. That same centrifugal force is what allows this rotary atomizer to break liquids into droplets. Relative to the photos above, the atomizer spins in a counter-clockwise direction. This motion stretches the fluid flowing off it into skinny, equally-spaced ligaments, which eventually break down into droplets.

Just how and when that break-up occurs depends on the fluid, as well as the characteristics of the spin. For Newtonian fluids like silicone oil — shown in the first two pictures — the break-up is driven by surface tension and happens relatively quickly. But with a viscoelastic fluid — shown in the last image — the elasticity of polymers in the fluid allow it to resist break-up for much longer. Instead, the ligaments form the beads-on-a-string instability. See more flows in action in the video below. (Video, image, and research credit: B. Keshavarz et al., video)