A frozen winter lake can hide surprisingly complex flows beneath its placid surface. Since water is densest at 4 degrees Celsius — just above the freezing point — mixing two water sources can lead to counterintuitive effects. A cold lake, for example, may contain water below 4 degrees Celsius, while a stream running into the lake is a bit warmer than 4 degrees Celsius. When the two parcels of water meet, they mix to form water at an intermediate temperature. But because of water’s density anomaly, that mixed water can wind up denser than the average of its parents. This is known as cabbeling.

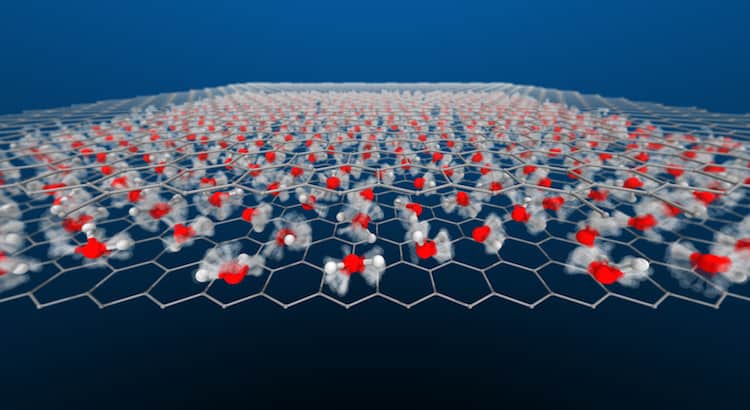

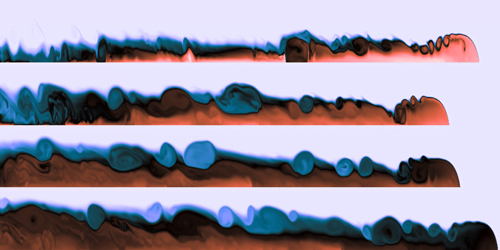

As shown in a recent study, this newly mixed water sinks to the bottom of the lake, forming a warm current that heats the lake from below. The researchers were able to model this current and its behavior over a range of conditions. Understanding these winter circulation patterns is key to tracking both nutrient transport and how pollutants spread in the ecosystem. (Image credit: lake – G. Murry, simulation – A. Grace et al.; research credit: A. Grace et al.; via APS Physics)