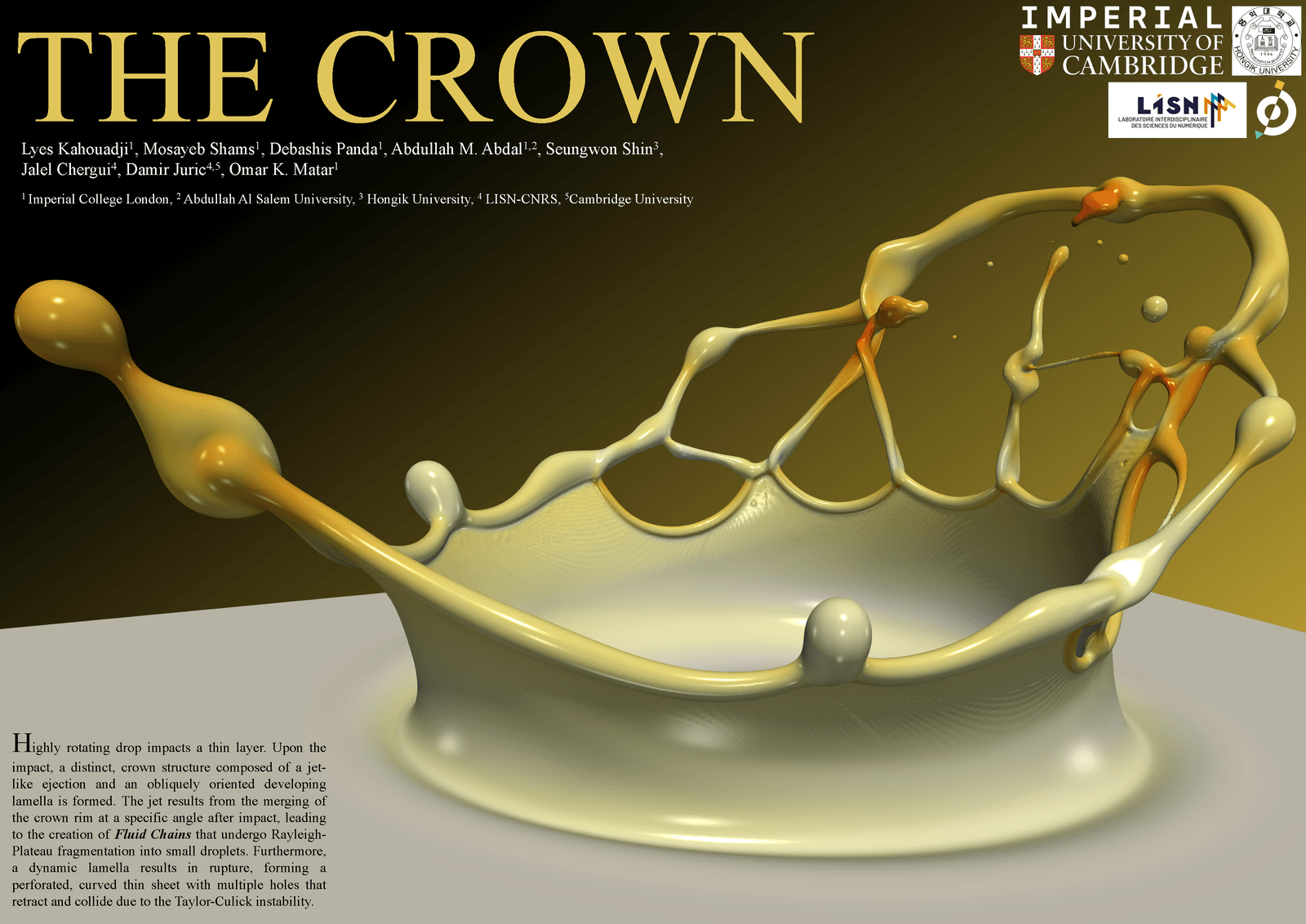

When a falling drop hits a thin layer of water, the impact sends up a thin, crown-shaped splash. This research poster shows a numerical simulation of such a splash in the throes of various instabilities. The crown’s thick edges are undergoing a Rayleigh-Plateau instability, breaking into droplets much the way a dripping faucet does. On the far side, the crown has rapidly expanding holes that pull back and collide. The still-intact liquid sheet at the base of the crown shows some waviness, as well, hinting at a growing instability there. (Image credit: L. Kahouadji et al.)

Tag: splashing

Charged Drops Don’t Splash

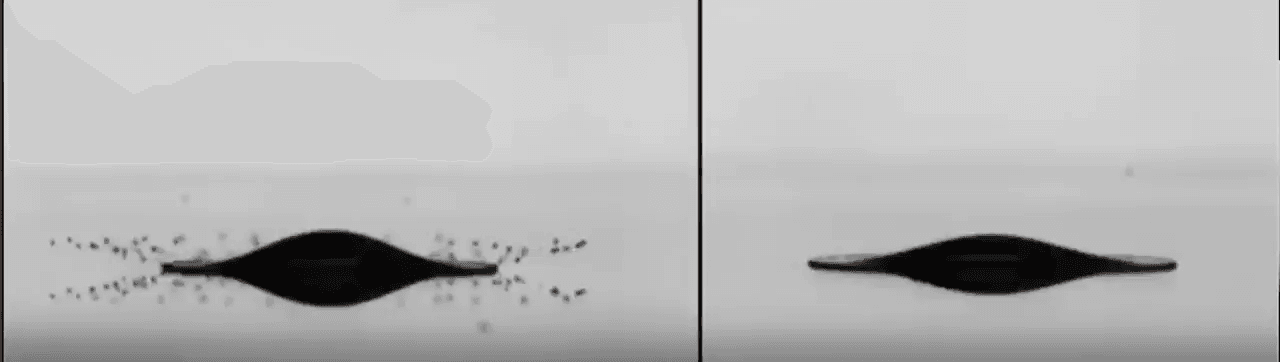

When a droplet falls on a surface, it spreads itself horizontally into a thin lamella. Sometimes — depending on factors like viscosity, impact speed, and air pressure — that drop splashes, breaking up along its edge into myriad smaller droplets. But a new study finds that a small electrical charge is enough to suppress a drop’s splash, as seen below.

The drop’s electrical charge builds up along the drop’s surface, providing an attraction that acts somewhat like surface tension. As a result, charged drops don’t lift off the surface as much and they spread less overall; both factors inhibit splashing.* The effect could increase our control of droplets in ink jet printing, allowing for higher resolution printing. (Image and research credit: F. Yu et al.; via APS News)

*Note that this only works for non-conductive surfaces. If the surface is electrically conductive, the charge simply dissipates, allowing the splash to occur as normal.

Splashing on Spheres

The splash of a droplet is a surprisingly complex phenomenon, depending not only on the droplet’s characteristics but also the surrounding air pressure, the roughness and temperature of the impact surface, and the surface’s curvature. In this study, researchers investigated the effects of surface curvature on splashing, finding that it’s harder for a drop to splash on spheres of smaller radius than ones with a larger radius of curvature.

In Image 1, the falling droplet coats the 2-mm sphere with no sign of splashing. But as the radius gets larger (Images 2 and 3), splashing becomes more and more pronounced. They found that the splash suppression is due to a modification of the lift force on the leading edge of the lamella, the thin liquid layer created as the drop impacts and spread. (Image, research, and submission credit: T. Sykes et al.; also available here)

360 Splashes

Beautiful as a splash is, why only enjoy it from a single angle? In this video, the artists behind Macro Room offer a 360-degree perspective on various splashes and fluid collisions. I especially enjoy watching the splash crowns falling back over and out of the various containers they use. What’s your favorite part? (Image and video credit: Macro Room)

Water Impacts

In the clean and simplified world of the laboratory, a droplet’s impact on water is symmetric. From a central point of impact, it sends out a ring of ripples, or even a crown splash, if it has enough momentum. But the real world is rarely so simple.

Here we see how droplets impact when the wind is blowing against them. The drops fall at an angle, creating an oblique cavity. Rings of ripples spread from the impact, but the ligaments of a splash crown form only on the leeward side. As the wind speed increases, so does the violence of the impact, eventually beginning to trap tiny pockets of air beneath the surface. Those miniature bubbles can spray droplets and aerosols into the air when they finally pop. (Image and video credit: A. Wang et al.)

Freezing Drop Impact

At the altitudes where aircraft fly, it’s often cold enough for water drops to freeze in seconds or less. Once attached to a wing, such frozen drops disrupt the flow, reducing lift and increasing drag. To help understand how such droplets freeze, scientists study droplet impact on cold surfaces. Starting at room temperature (counter-clockwise from upper left), a drop will spread on the surface, then retract. When the temperature is colder, parts of the droplet freeze before retraction completes, leaving a thin sheet with a thicker center. At even colder temperatures, the droplet’s rim destabilizes and freezing occurs before the droplet has time to retract fully. And at the coldest temperatures, the droplet breaks apart into a frozen splash. (Image and video credits: V. Thievenaz et al.)

Worthington and His Jets

If you’ve been around fluid mechanics for very long, you’ve probably noticed that we like to name things after people. (Mostly dead, white guys, but that’s another subject.) Whenever someone describes or explains a new phenomenon, it tends to get their name attached to it. Some of the common names in fluid dynamics – Reynolds, Rayleigh, Kelvin, Taylor, von Karman, Prandtl – read like a who’s-who of nineteenth and twentieth century physics. This video gives some historical insight into a couple of those figures – particularly Arthur Worthington, who is known for his contributions to the understanding of splashes. Be sure to check out some of his awesome illustrations and photos. Can you imagine being able to piece together splash physics like that without high-speed video?! (Video credit: Objectivity; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Using Paper to Avoid Splashback

Daily life and countless pool parties have taught us all that objects falling into water create a splash. Sometimes that splash is undesirable, and while there are many ways to tune a splash – by adding surfactants or changing the fluid’s viscosity – there’s a relatively common one that’s escaped scientific study until now. Researchers looked at how splashes change when you add a thin, penetrable fabric – commonly known as toilet paper – to the water surface.

Now, the common assumption is that adding a sheet of toilet paper can prevent splashback, but the story is not quite that simple. On the left, you see a splash generated without toilet paper. Because the ball is hydrophilic (water-loving), it does not pull any air into a cavity as it passes. There’s a nice axisymmetric Worthington jet formed, and it doesn’t splash very high, although some of the satellite droplets go quite a bit higher.

On the right, we see a splash with a single sheet of toilet paper. In this case, the impact of the sphere penetrates the paper, and the way the paper deforms causes air to get sucked down into a cavity behind the ball. That creates a wider, amorphous jet that rebounds higher than the jet in clean water, though it does not shed satellite drops.

The researchers found that single and even double sheets of toilet paper can actually increase the height of the splash jet if the object penetrates them. The hole the object makes actually helps focus the jet. Adding a couple more layers, though, can eliminate splashing completely. (Image and research credit: D. Watson et al.)

Rim Break-Up

Splashing drops often expand into a liquid sheet and spray droplets from an unstable rim. Although this behavior is key to many natural and industrial processes, including disease transmission and printing, the physics of the rim formation and breakup has been difficult to unravel. But a new paper offers some exciting insight into this unsteady process.

The researchers found that if they carefully tracked the instantaneous, local acceleration and thickness of the rim, it always maintained a perfect balance between acceleration-induced forces and surface tension. That means that even though different points on the rim appear very different, there’s a universality to how they behave. They found that this rule held over a remarkably large range of situations, including across fluids of different viscosities and splashes on various surfaces. (Image and research credit: Y. Wang et al.; via MIT News; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Oil Splatters

Most cooks have experienced the unpleasantness of getting splattered with hot oil while cooking. Here’s a closer look at what’s actually going on. The pan is covered by a thin layer of hot olive oil. Whenever a water drop gets added – from, say, those freshly washed greens you’re trying to saute – it sinks through the oil due to its greater density. Surrounded by hot oil and/or pan, the water heats up and vaporizes with a sudden expansion. This throws the overlying oil upward, creating long jets of hot oil that break into flying droplets. These are what actually hit you. This is a small-scale demonstration, but it gets at the heart of why you don’t throw water on an oil fire. (Image credit: C. Kalelkar and S. Paul, source)