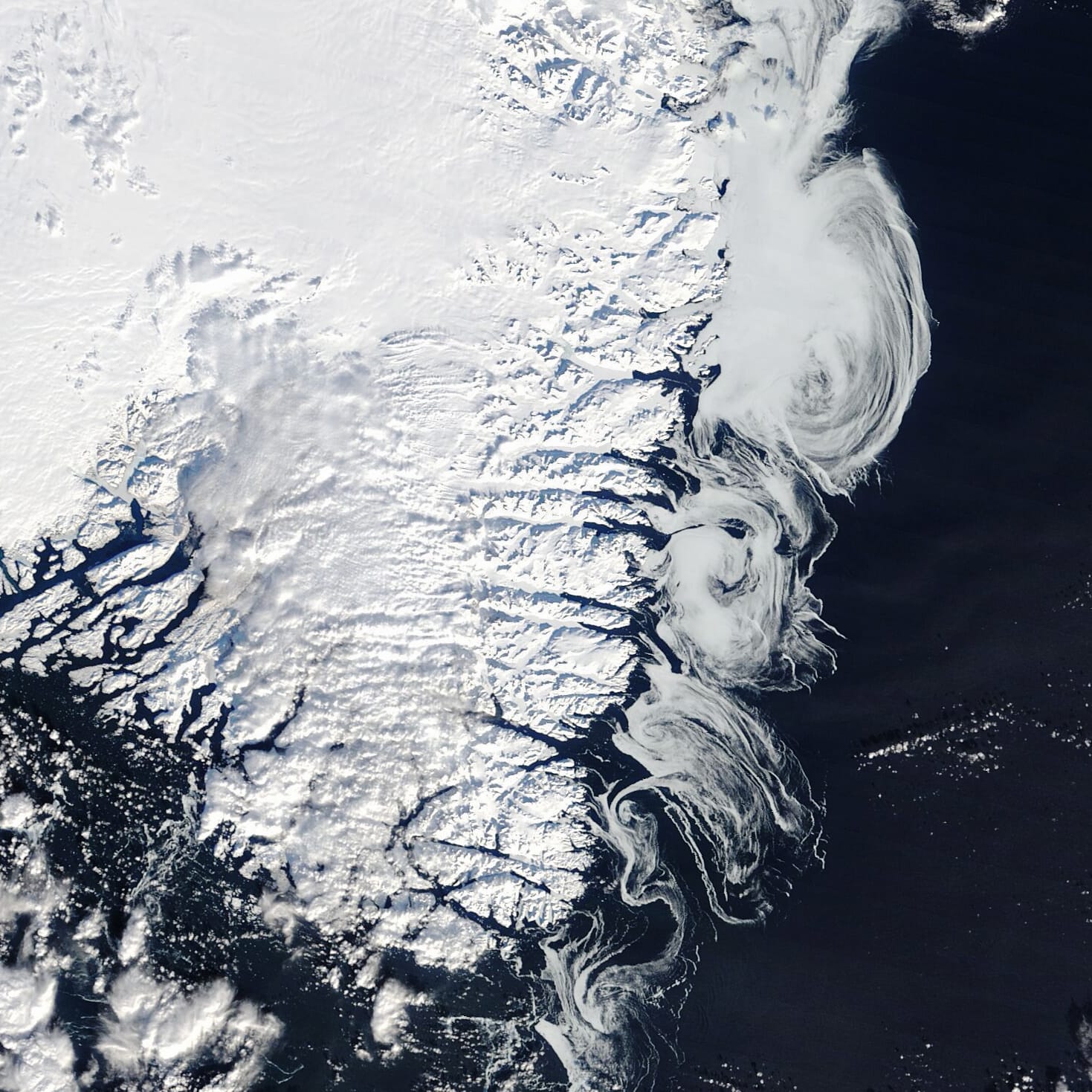

Fresh snow shines white on the southern end of Greenland in this satellite image, taken in late February 2025. Whorls of sea ice sit off the coast, where they trace out patterns that reflect the winds and ocean currents of the region. Arctic sea ice typically reaches its largest extent by early March before experiencing a long season of melting. Both the presence and absence of sea ice have a large effect on the Arctic regions. Sea ice helps dampen wave activity; without it, seas are higher and more dynamic, creating more aerosols that seed cloud cover in the Arctic and elsewhere. (Image credit: L. Dauphin; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Tag: sea ice

Salt and Sea Ice Aging

Sea ice’s high reflectivity allows it to bounce solar rays away rather than absorb them, but melting ice exposes open waters, which are better at absorbing heat and thus lead to even more melting. To understand how changing sea ice affects climate, researchers need to tease out the mechanisms that affect sea ice over its lifetime. A new study does just that, showing that sea ice loses salt as it ages, in a process that makes it less porous.

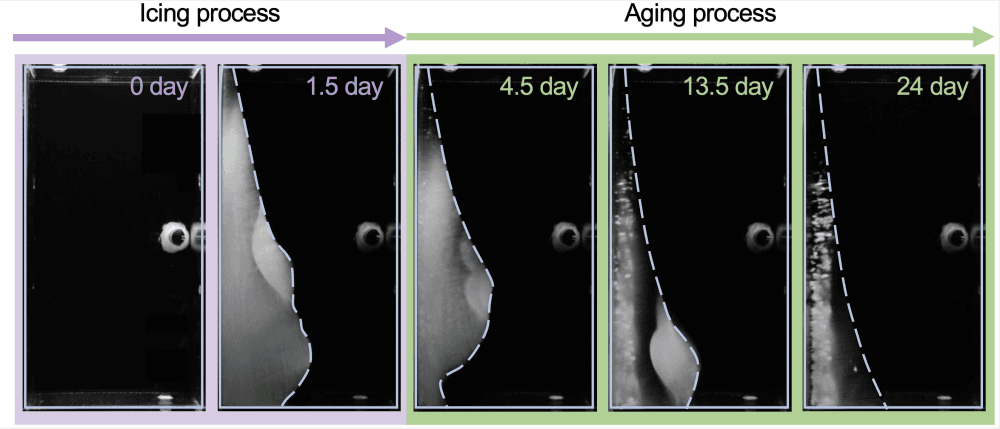

Researchers built a tank that mimicked sea ice by holding one wall at a temperature below freezing and the opposite wall at a constant, above-freezing temperature. Over the first three days, ice formed rapidly on the cold wall. But it did not simply sit there, once formed. Instead, the researchers noticed the ice changing shape while maintaining the same average thickness. The ice got more transparent over time, too, indicating that it was losing its pores.

Looking closer, the team realized that the aging ice was slowly losing its salt. As the water froze, it pushed salt into liquid-filled pores in the ice. One wall of the pore was always colder than the others, causing ice to continue freezing there, while the opposite wall melted. Over time, this meant that every pore slowly migrated toward the warm side of the ice. Once the pore reached the surface, the briny liquid inside was released into the water and the ice left behind had one fewer pores. Repeated over and over, the ice eventually lost all its pores. (Image credit: T. Haaja; research credit and illustration: Y. Du et al.; via APS)

Growing Ice

While much attention is given to the summer loss of sea ice, the birth of new ice in the fall is also critical. Ice loss in the summer leaves oceans warmer and waves larger since wind can blow across longer open stretches. Those warmer waters and more dynamic waves affect how ice forms once autumn sets in. Higher waves mean that ice tends to form in “pancakes” like those seen here. Pancake ice is small — typically under 1 meter wide — and can only be observed from nearby, since they’re smaller than typical satellite resolution. Only once there’s enough pancake ice to dampen the waves will the pieces begin to cement together to form larger pieces that will form the basis of the year’s new ice. (Image credit: M. Smith; see also Eos)

Disappearing Sea Ice Ridges

As blocks of sea ice shift and float, they can press together, forming ridges spaced every few hundred meters or so. A new study uses aerial observations from recent decades to show that these sea ridges are getting smaller in both size and number, a smoothing of Arctic topography that has many consequences.

The team showed that the overall changes in the sea ridges correspond to a loss of older sea ice. The current smoother sea ice presents less drag to winds and currents, which might suggest that the ice is slower-moving, but instead the opposite seems true. Scientists are not sure why the ice is moving faster, though faster ocean currents may play a role.

Another consequence of smoother sea ice is wider, shallower melt ponds each summer. These wider ponds increase the amount of sunlight the ice absorbs, hastening melting even further. (Image credit: USGS; research credit: T. Krumpen et al.; via Eos)

Tracking Ice Floes

To understand why some sea ice melts and other sea ice survives, researchers tracked millions of floes over decades. This herculean undertaking combined satellite data, weather reports, and buoy data into a database covering nearly 20 years of data. With all of that information, the team could track the changes to specific pieces of ice rather than lumping data into overall averages.

They found that an ice floe’s fate depended strongly on the route it took: ice that slipped from its starting region into warmer, more southern regions was likely to melt. They also saw region-specific effects, like that thick sea ice was more likely to melt in the East Siberian Sea’s summer, possibly due to warmer currents. The comprehensive, fine-grained analyses possible with this ice-tracking technique offer a chance to understand why some Arctic regions are more vulnerable to warming than others. (Image credit: D. Cantelli; research credit: P. Taylor et al.; via Eos)

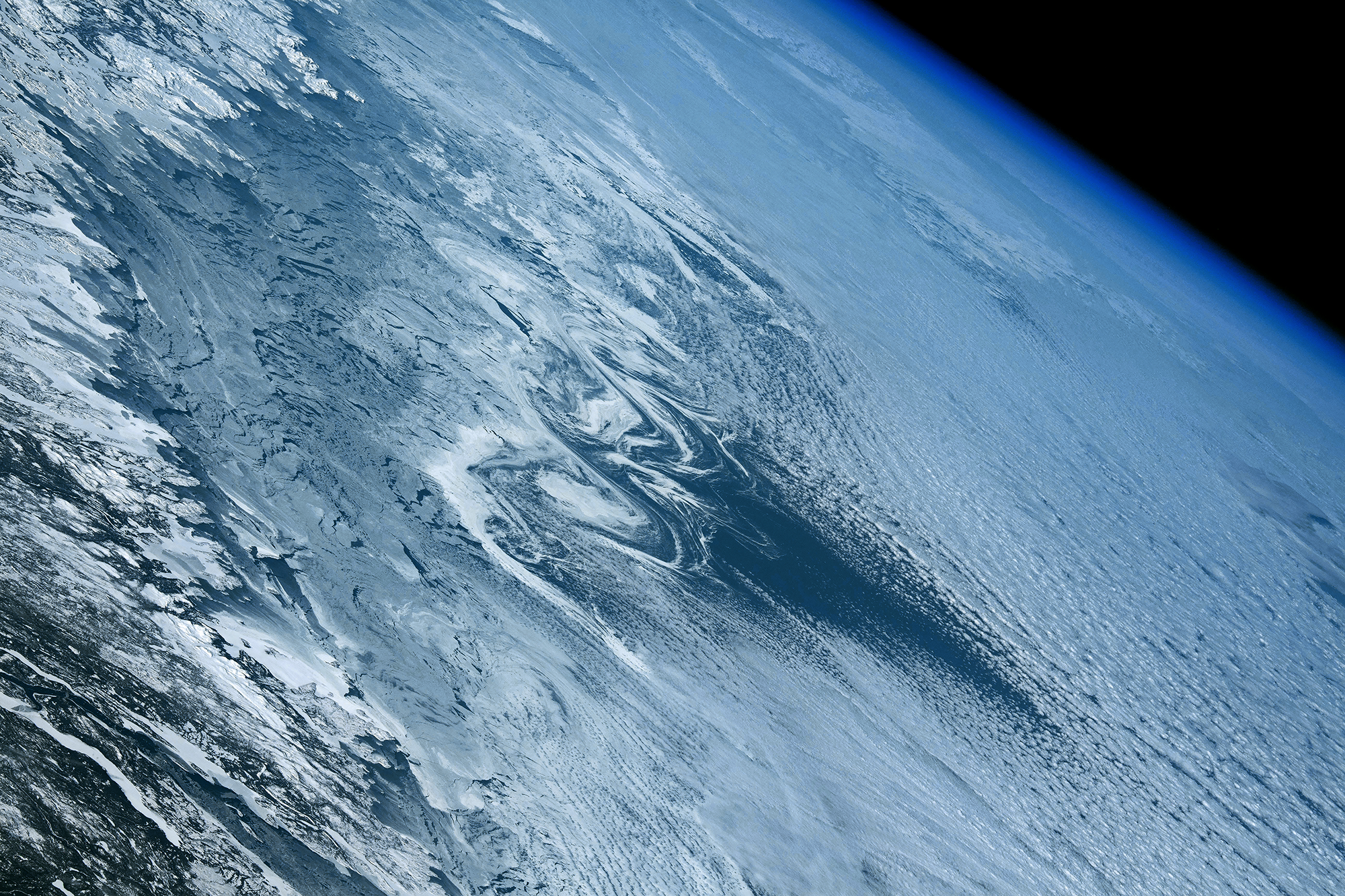

Lines of Ice Eddies

In February 2024, the North Atlantic’s sea ice reached its furthest extent of the season, limning the coastline with tens of kilometers of ice. These images — both capturing the Labrador coast on the same day — show the swirling patterns marking the wispy edges of ice field. In this region, the ice is likely following an eddy in the ocean below. Eddies like these can form along the edges where warm and cold currents meet. An ice eddy is particularly special, though, as the water must be warm enough to fragment the sea ice, but not so warm that it melts the smaller ice pieces. (Image credit: top – NASA, lower – M. Garrison; via NASA Earth Observatory)

This satellite image shows sea ice off the Labrador coast, on the same day in February 2024.

Sea Ice Swirls

Fragments of sea ice tumble and swirl in this satellite image of Greenland’s east coast. In spring, Arctic sea ice journeys down the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard. Along the way, large ice floes break — and melt — into smaller pieces. Large pieces of sea ice are visible closer to the coastline, but the smaller individual floes get, the wispier they appear in the satellite image. In the haziest portions of the image, the ice may be only meters across. In recent years, less and less Arctic sea ice has survived the journey southward, shifting the temperature and salinity of Arctic contributions to global ocean circulation. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

Waves Break Up Floating Rafts

Small particles can float on a liquid, held together as a raft through capillary action. But those rafts — like the tea skin below — break up when waves jostle them. In this study, researchers looked at how standing waves broke up a raft of graphite powder. Although the raft’s break-up resembles fields of sea ice breaking apart, the researchers found that different mechanisms were responsible. In their experiment, waves pushed and pulled horizontally at the raft, causing it to fracture. But that push-and-pull is negligible in sea ice, where sheets instead break from the up-and-down motion of waves vertically bending the ice. Nevertheless, the new insights are valuable for various biofilms and some ice floes. (Image and research credit: L. Saddier et al.; via APS Physics)

The skin atop a cup of tea breaks up into polygons after stirring with a spoon. Although the effect resembles sea ice breakup, the specific wave mechanism differs.

Swirling Sea Ice

The Sea of Okhotsk is the northern hemisphere’s southernmost sea that seasonally freezes. Caught between the Siberian coast and the Kamchatka Peninsula, cold air from Siberia helps freeze water kept at lower salinity due to freshwater run-off. This image, taken in May 2023, shows free-floating sea ice forming spirals driven by wind and waves. Small islands off the eastern coast (right side in image) are likely responsible for the swirling eddies seen there. Like phytoplankton blooms and sediment swirls in warmer seasons, the sea ice acts as a tracer to reveal flow. (Image credit: W. Liang; via NASA Earth Observatory)

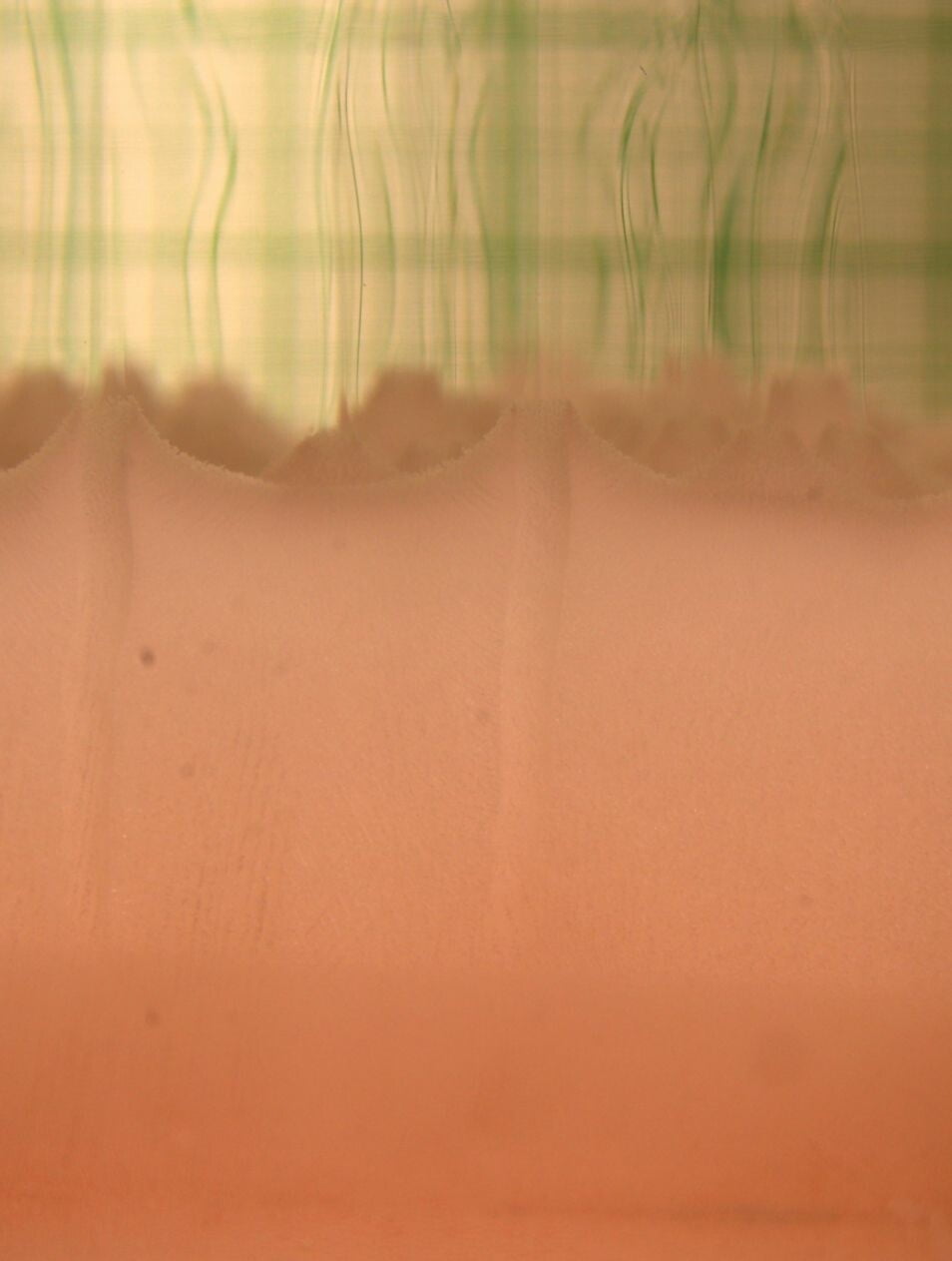

Mushy Layers

In many geophysical and metallurgical processes, there is a stage with a porous layer of liquid-infused solid known as a mushy layer. Such layers form in sea ice, in cooling metals, and even in the depths of our mantle. Within the mushy layer, temperature, density, and concentration can vary dramatically from one location to another.

The image above shows a mushy layer made from a mixture of water and ammonium chloride. Above the mushy layer, green plumes drift upward, carrying lighter fluid. Look closely within the mushy layer and you’ll see narrow channels feeding up to the surface. These are known as chimneys. In sea ice, chimneys like these carry salty brine out of the ice and into the seawater, increasing its salinity. See this Physics Today article for more details on the dynamics of mushy layers. (Image credit: J. Kyselica; via Physics Today)