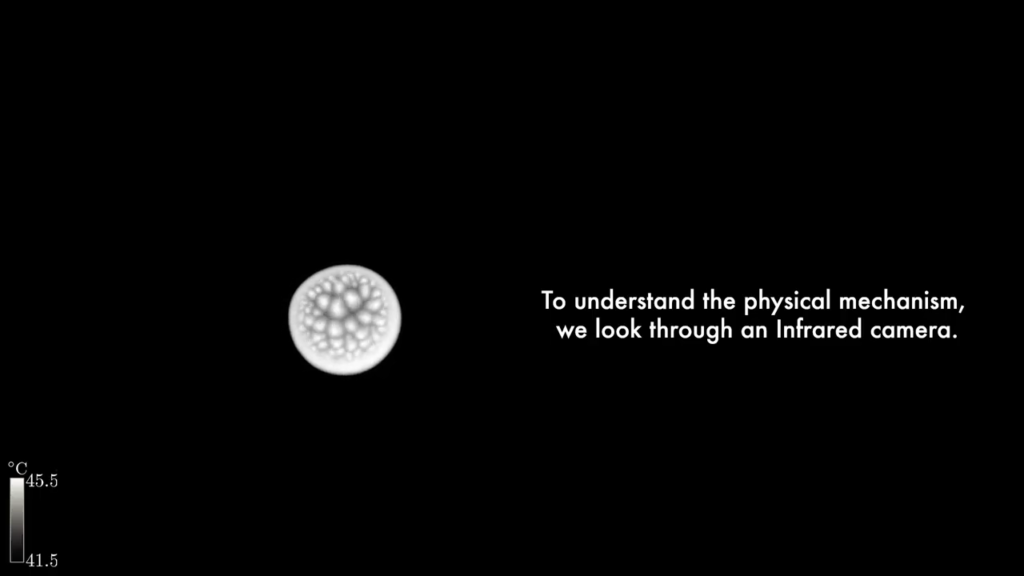

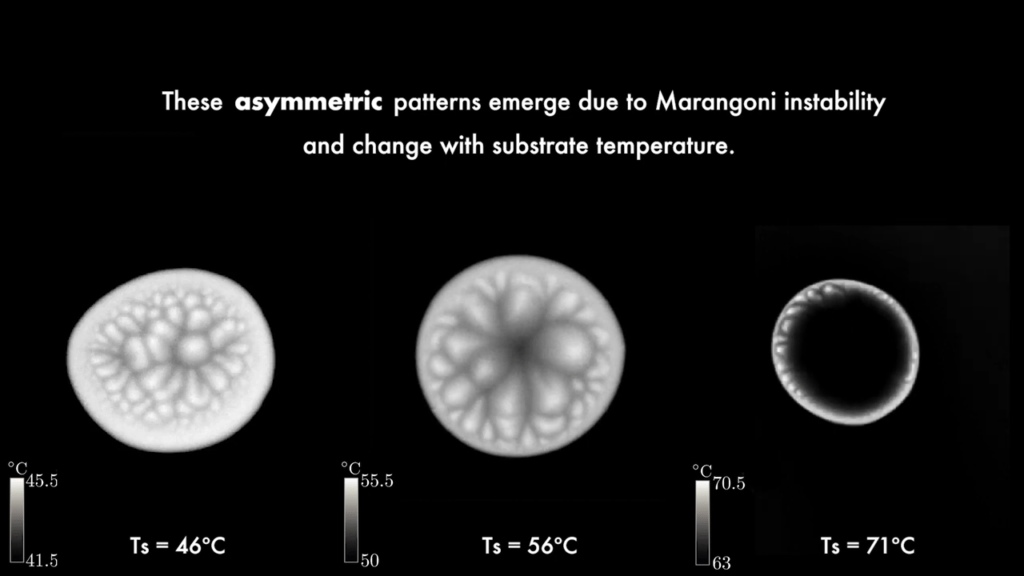

Drops of ethanol on a heated surface contract and self-propel as they evaporate. My first thought upon seeing this was of Leidenfrost drops, but the surface is not nearly hot enough for that effect. Instead, it’s significantly below ethanol’s boiling point. Looking at the drops in infrared reveals beautiful, shifting patterns of convection cells on the drop. The patterns are driven by the temperature difference along the drop; at the bottom, the drop is warmest, and at its apex, it is coldest. Those differences in temperature create differences in surface tension, which drives a surface flow that breaks the drop’s symmetry. The asymmetry, the authors suggest, is responsible for the drop’s propulsion. (Image and video credit: N. Kim et al.)

Tag: Benard-Marangoni convection

Convection Without Heat

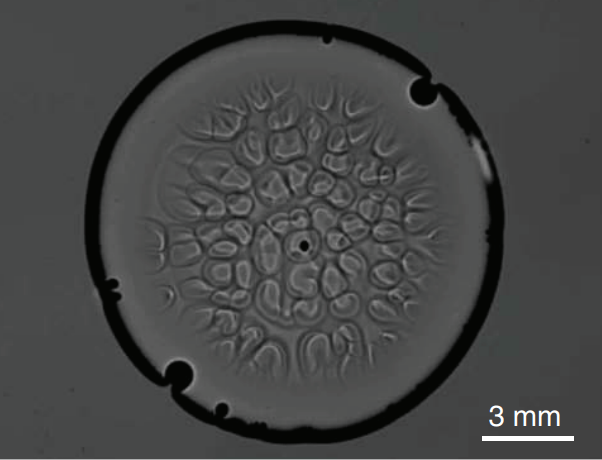

Glycerol is a sweet, highly viscous fluid that’s very good at absorbing moisture from the ambient air. That’s why a drop of pure glycerol in laboratory conditions quickly develops convection cells – even when upside-down, as shown above. This is not the picture of Bénard-Marangoni convection we’re used to. There’s no temperature or density change involved; in fact, there’s no buoyancy involved at all! This convection is driven entirely by surface tension. As glycerol at the surface absorbs moisture, its surface tension decreases. This generates flow from the center of a cell toward its exterior, where the surface tension is higher. Conservation of mass, also known as continuity, requires that fresh, undiluted glycerol get pulled up in the wake of this flow. It, too, absorbs moisture and the process continues. (Image credit: S. Shin et al., pdf)

Convection

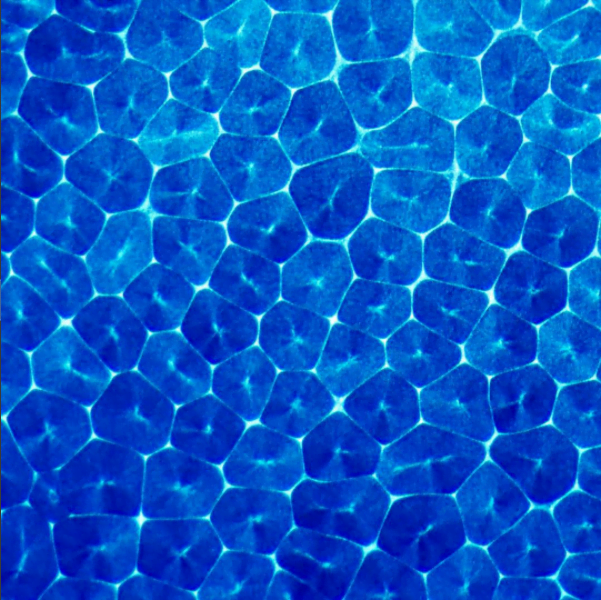

Blue paint in alcohol forms an array of polygonal convection cells. We’re accustomed to associating convection with temperature differences; patterns like the one above are seen in hot cooking oil, cocoa, and even on Pluto. In all of those cases, temperature differences are a defining feature, but they are not the fundamental driver of the fluid behavior. The most important factors – both in those cases and the present one – are density and surface tension variations. Changing temperature affects both of these factors, which is why its so often seen in Benard-Marangoni convection.

For the paint-in-alcohol, density and surface tension differences are inherent to the two fluids. Because alcohol is volatile and evaporates quickly, its concentration is constantly changing, which in turn changes the local surface tension. Areas of higher surface tension pull on those of lower surface tension; this draws fluid from the center of each cell toward the perimeter. At the same time, alcohol evaporating at the surface changes the density of the fluid. As it loses alcohol and becomes denser, it sinks at the edges of the cell. Below the surface, it will absorb more alcohol, become lighter, and eventually rise at the cell center, continuing the convective process. (Image credit: Beauty of Science, source)

Convection Visualization

Here on Earth a fascinating form of convection occurs every time we put a pot of water on the stove. As the fluid near the burner warms up, its density decreases compared to the cooler fluid above it. This triggers an instability, causing the cold fluid to drift downward due to gravity while the warm fluid rises. Once the positions are reversed, the formerly cold fluid is being heated by the burner while the formerly hot fluid loses its heat to the air. The process continues, causing the formation of convection cells. The shapes these cells take depend on the fluid and its boundary conditions. For the pot of water on the stove and in the video above, the surface tension of the air/water interface can also play a role in modifying the shapes formed. The effects caused by the temperature gradient are called Rayleigh-Benard convection. The surface tension effects are sometimes called Benard-Marangoni convection.

Solutal Convection

Solutal convection, rather than relying on temperature gradients, can occur due to gradients in concentration or in surface tension. While less spectacular than this previously posted video, this video contains a nice simplified explanation of the mechanism. And, as noted in the video, this is a demo you can do yourself at home.