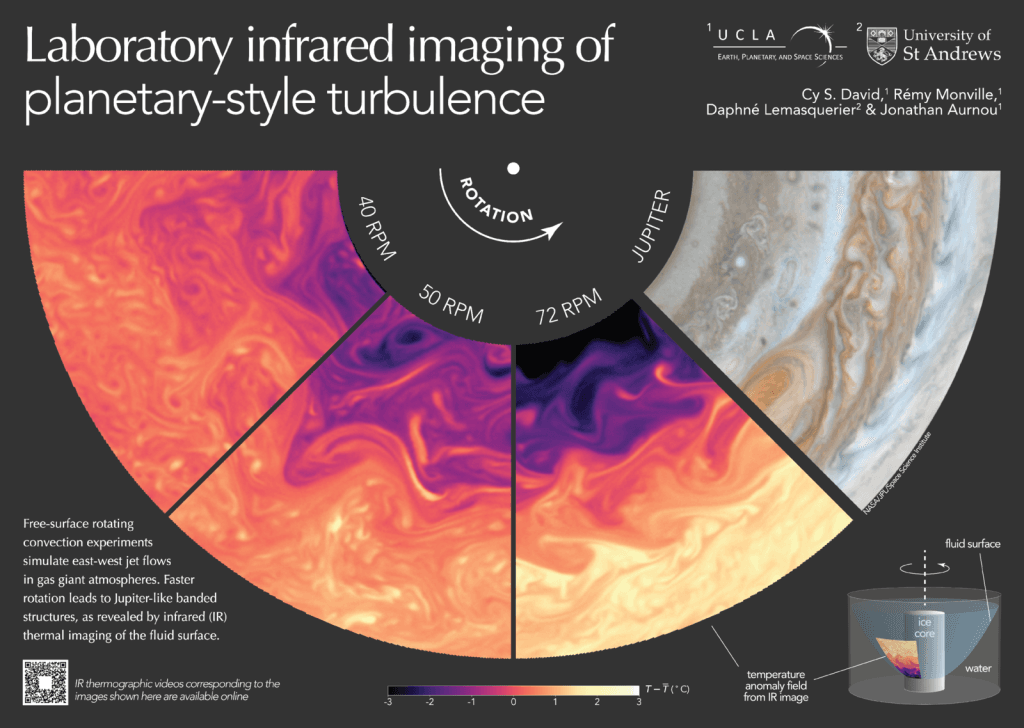

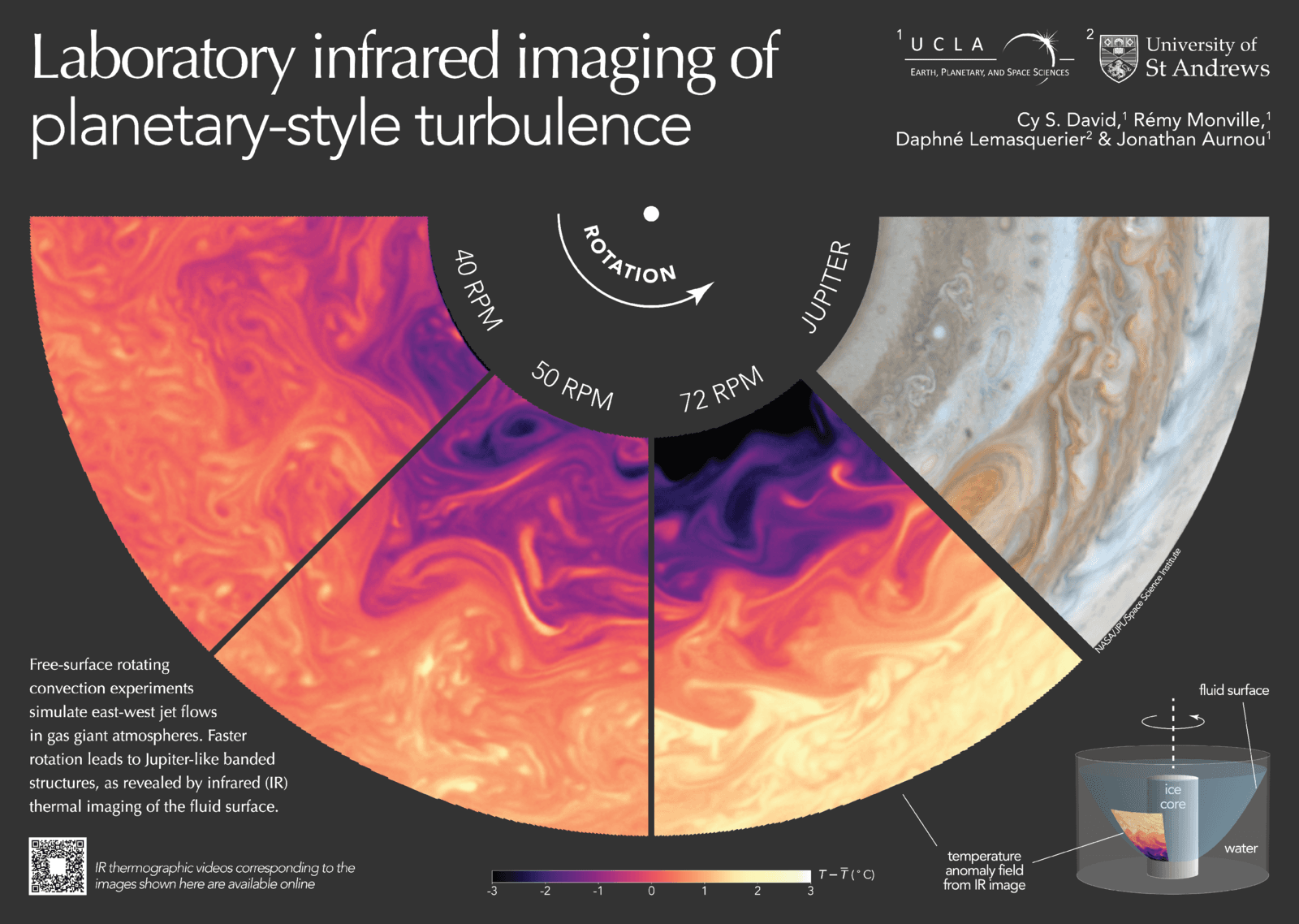

The vivid bands of a gas giant like Jupiter come from the planet’s combination of rotation and convection. It’s possible to create the same effect in a lab by rapidly spinning a tank of water around a central ice core. That’s the physical set-up behind this research poster–note the illustration in the lower right corner. The central snapshots show how temperature gradients on the water surface change the faster the tank rotates. At higher rotational speeds, the parabolic water surface gets ever steeper and Jupiter-like temperature bands form. (Image credit: C. David et al.)