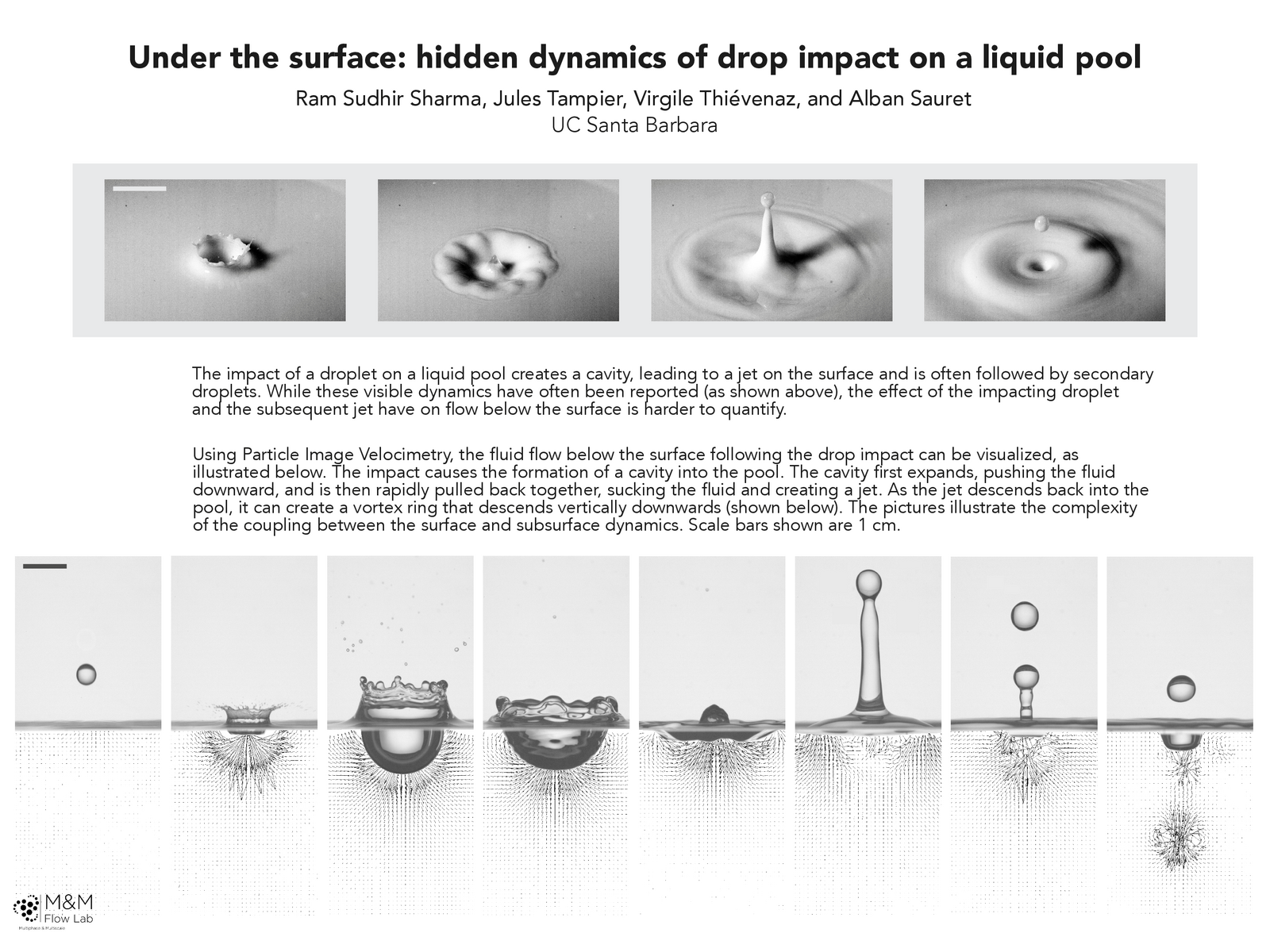

When bubbles at the surface of the ocean pop, they can send up a spray of tiny droplets that carry salt, biomass, microplastics, and other contaminants into the atmosphere. Teratons of such materials enter the atmosphere from the ocean each year. To better understand how contaminants can cross from the ocean to the atmosphere, researchers studied what happens when a oil-coated water bubble pops.

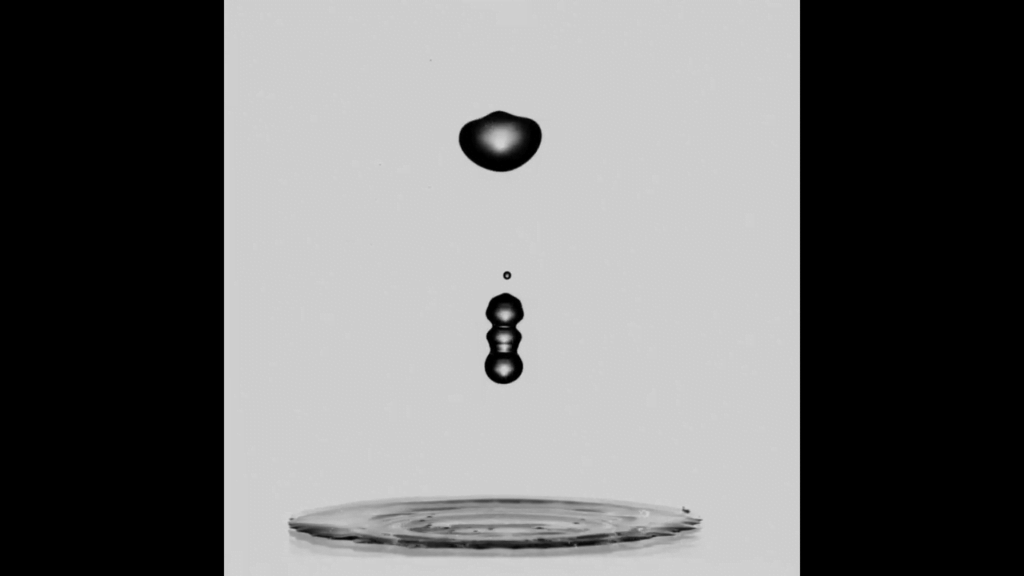

The team looked at bubbles about 2 millimeters across, coated in varying amounts of oil, and observed their demise via high-speed video. When the bubble pops, capillary waves ripple down into its crater-like cavity and meet at the bottom. That collision creates a rebounding Worthington jet, like the one above, which can eject droplets from its tip.

The team found that the oil layer’s thickness affected the capillary waves and changed the width of the resulting jet. They were able to build a mathematical model that predicts how wide a jet will be, though a prediction of the jet’s velocity is still a work-in-progress. (Image credit: Р. Морозов; research credit: Z. Yang et al.; via APS)