The latest FYFD/JFM video is out! May brings us a look at the incredible flight of dandelion seeds, numerical simulations that reveal the flow above forest canopies, and a look at bee-inspired flapping wing robots being developed for exploring Mars! Learn about all this in the video below, and, if you’ve missed other videos in the series, you can catch up here. (Image and video credit: N. Sharp and T. Crawford)

Tag: Mars

Water on Mars

Recurring slope lineae (RSL) are seasonal features on Mars that leave behind gullies similar to those left by running water on Earth. Their discovery a few years ago has prompted many experiments at Martian conditions to determine how these features form. At Martian surface pressures and temperatures, it’s not unusual for water to boil. And that boiling, as some experiments have shown, introduces opportunities for new transport mechanisms.

Researchers found that water in “warm” (T = 288 K) sand boils vigorously, ejecting sand particles and creating larger pellets of saturated sand. Water continues boiling out of the pellets once they form, creating a layer of vapor that helps levitate them as they flow downslope. The effect is similar to the Leidenfrost effect with drops of water sliding on a hot skillet; there’s little friction between the pellet and the surface, allowing it to travel farther.

The mechanism is quite efficient in experiments under Earth gravity and would be even more so under Mars’ lower gravity. It also requires less water than alternative explanations. The pellets that form are too small to be seen by the satellites we have imaging Mars, but the tracks they leave behind are similar to the RSL seen above. (Image credit: NASA; research credit: J. Raack et al., 1, 2; via R. Anderson; submitted by jpshoer)

The Winds of Mars

The Martian atmosphere is scant compared to Earth’s, but its winds still sculpt and change the surface regularly. The average atmospheric pressure on Mars is only 0.6% of Earth’s, and the density is similarly low at 1.7% of Earth’s. Despite this thinness, Martian winds are still substantial enough to shift sands on a daily basis, as shown above. These two images were taken one Martian day apart, showing how sand ripples moved and how the Curiosity rover’s tracks can be quickly obscured. Part of the reason Mars’ scant atmosphere is still so good at moving sand is that Martian gravity is roughly one-third of ours; if the sand is lighter, it doesn’t take as much force to move! (Image credit: NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS)

Gravity Waves on Mars

It may look like grainy, black and white static from a 20th-century television, but this animation shows what may be the first view of gravity waves seen from the ground on another planet. The animation was stitched together from photos taken by the Mars Curiosity rover’s navigation camera, and it shows a line of clouds approaching the rover’s position.

Gravity waves are common on Earth, appearing where disturbances in a fluid propagate like ripples on a pond. In the atmosphere, this can take the form of stripe-like wave clouds downstream of mountains; internal waves under the ocean are another variety of gravity wave. If these are, in fact, Martian gravity waves, they are likely the result of wind moving up and over topography, much like their Terran counterparts. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/York University; research credit: J. Kloos and J. Moores, pdf; via Science; h/t Cocktail Party Physics)

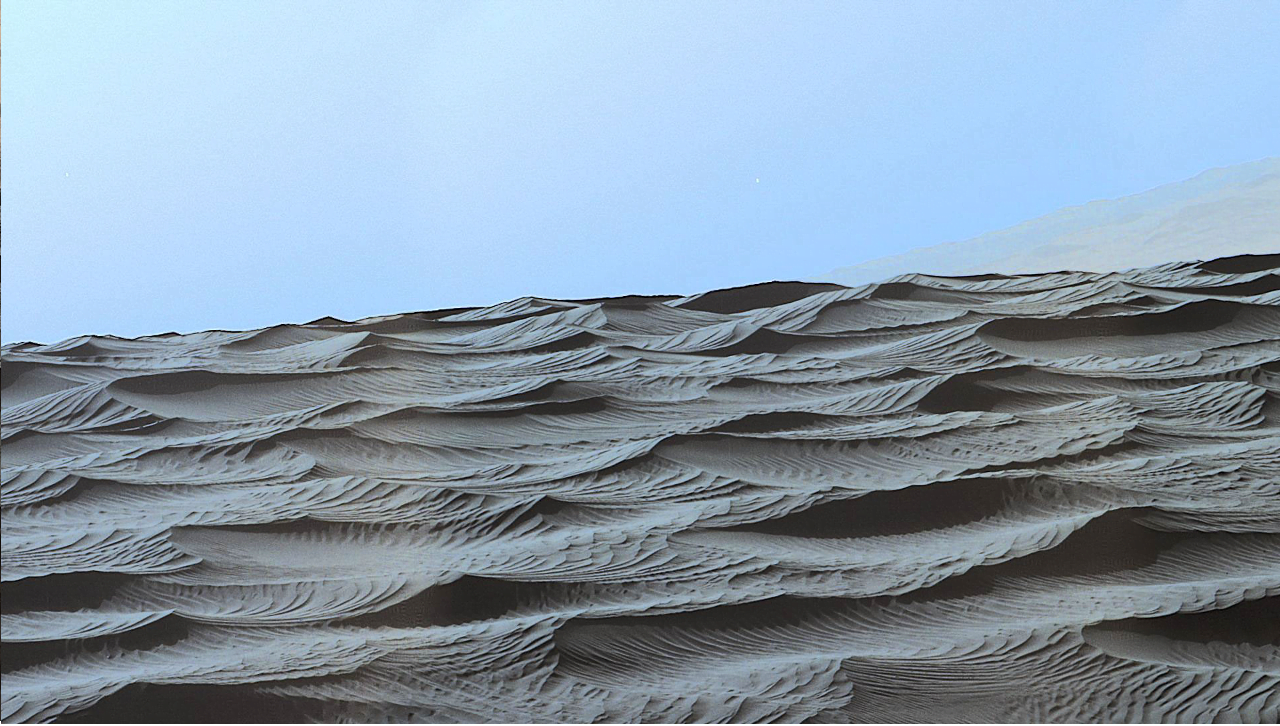

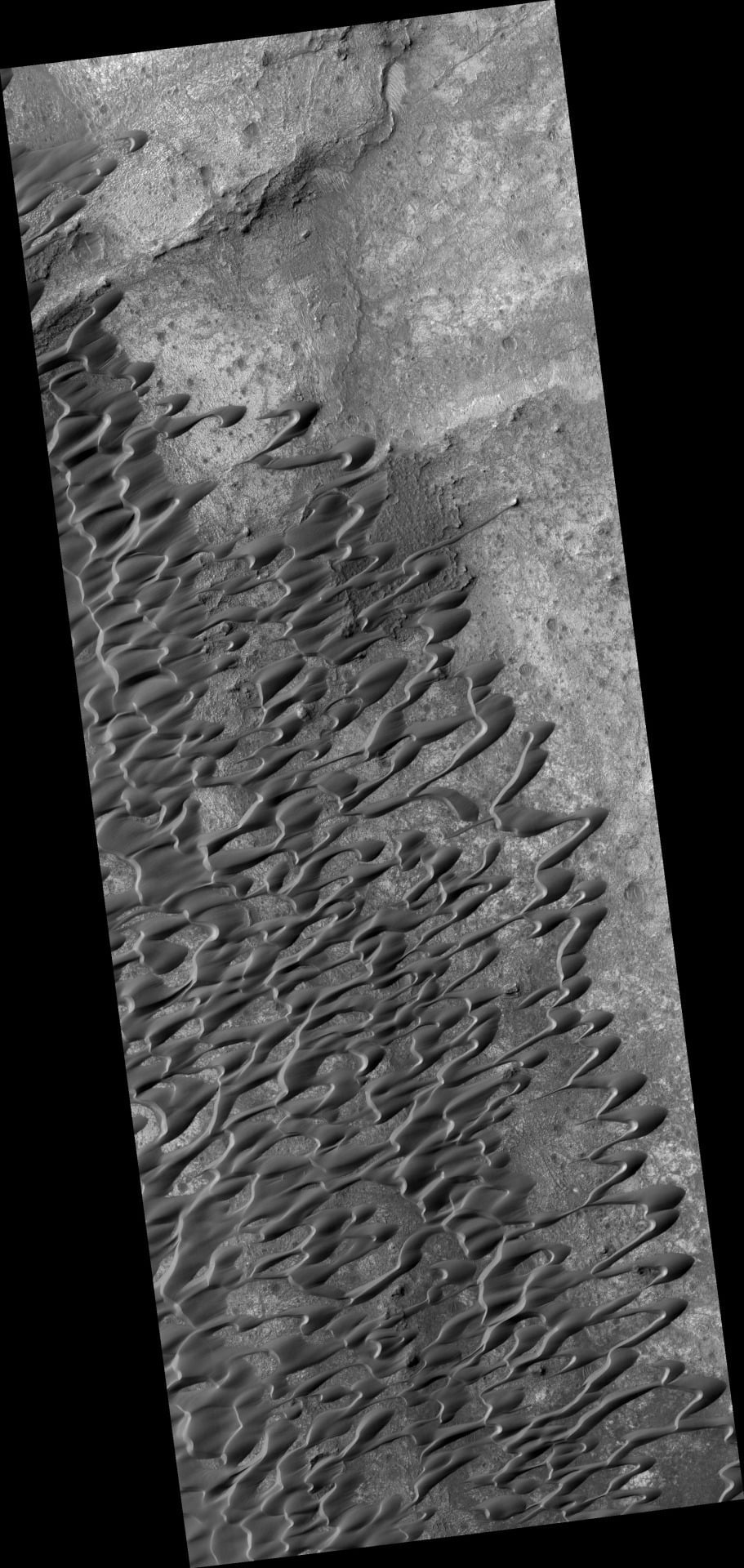

Martian Ripples

Earth and Mars both feature fields of giant sand dunes. The huge dunes are shaped by the wind and miniature avalanches of sand, and their surface is marked by small ripples less than 30 centimeters apart. These little ripples are formed when sand carried by the wind impacts the dunes. But Martian dunes have a second, larger kind of ripple, too. These sinuous, curvy ripples lie about 3 meters apart and cast the dark shadows seen in the images above. On Earth we see ripples like these underwater, where water drags sand along the surface. On Mars, the same process is thought to play out with the wind, and so scientists have named these wind-drag ripples. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/MSSS; via APOD, full-res; submitted by jshoer)

Boiling on Mars

Today’s Mars is cold and dry, with a thin and insubstantial atmosphere. One of the challenges facing planetary scientists is unraveling the processes behind the complex terrain we can observe on the surface. Without flowing water, how do we explain these features? A new experiment suggests that the answer lies in boiling.

Surface conditions on Mars include atmospheric pressures low enough to be below the triple point of water* – the critical temperature and pressure where water vapor, liquid water, and ice can all exist simultaneously. This means that liquid water is unstable under Martian conditions; any water that seeped up to the surface would immediately begin to boil. That explosive boiling ejects sand particles, as seen in the animation above. The authors suggest that this hybrid process of wet percolation combined with vaporous ejection of sediment may better explain the Martian surface features we observe. (Image credit: M. Masse et al., source: Supplementary Movie 3; via Gizmodo; submitted by Paul vdB)

* The evidence we’ve seen so far on Mars points to briny water flowing near the surface. Although brines have lower freezing temperatures than pure water, the authors’ argument holds for them, as well. The boiling is simply not as vigorous.

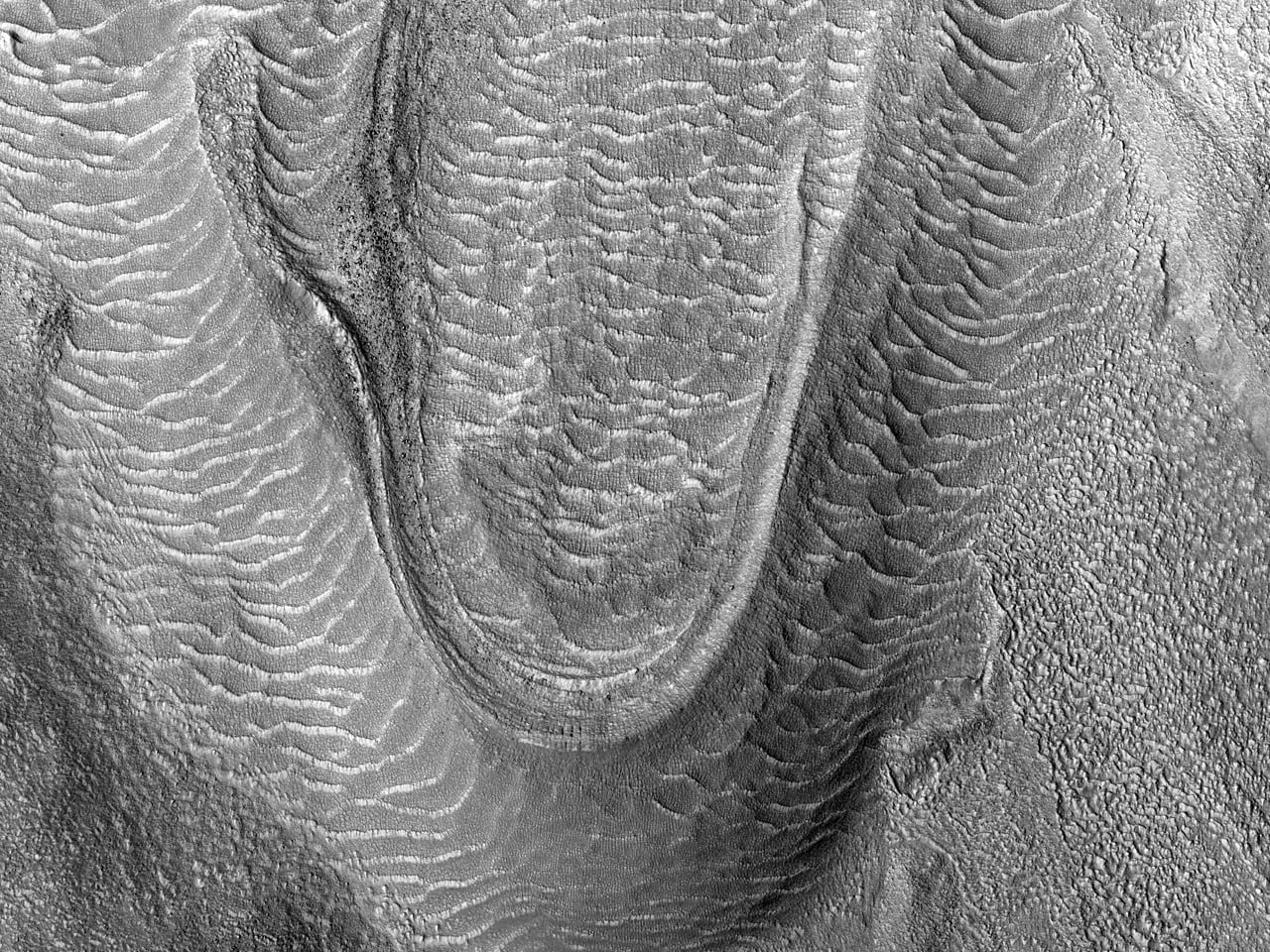

Martian Viscous Flow

These images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter show what are called viscous flow features. They are the Martian equivalent of glacial flow. Such features are typically found in Mars’ mid-latitudes.

Ground-penetrating radar studies of Mars have shown that some of these features contain water ice covered in a protective layer of rock and dust, making them true glaciers. Another study of similar Martian surface features found that their slope was consistent with what could be produced by a ~10 m thick layer of ice and dust flowing superplastically over a timescale equal to the estimated age of the surface features. Superplastic flow occurs when solid matter is deformed well beyond its usual breaking point and is one of the common regimes for glacial ice flow on Earth. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/U. of Arizona; via beautifulmars)

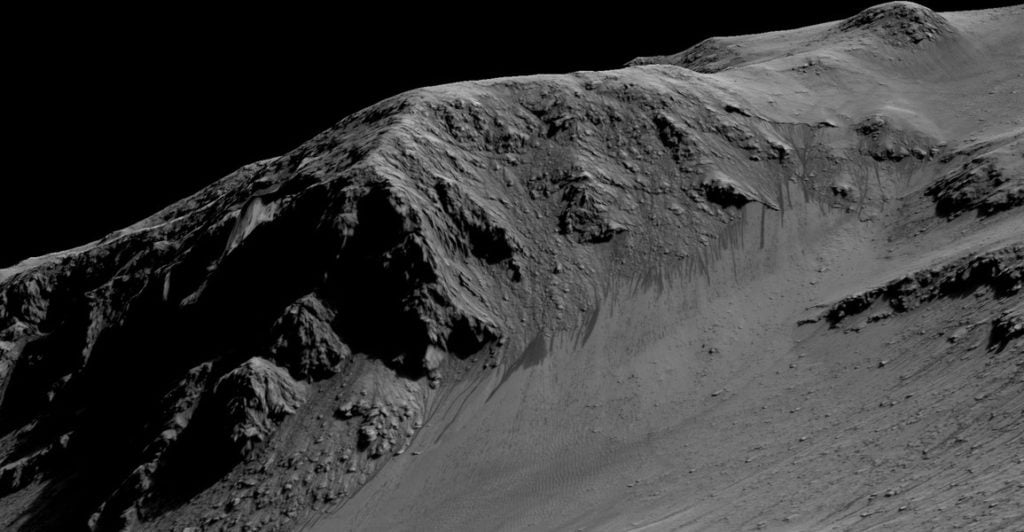

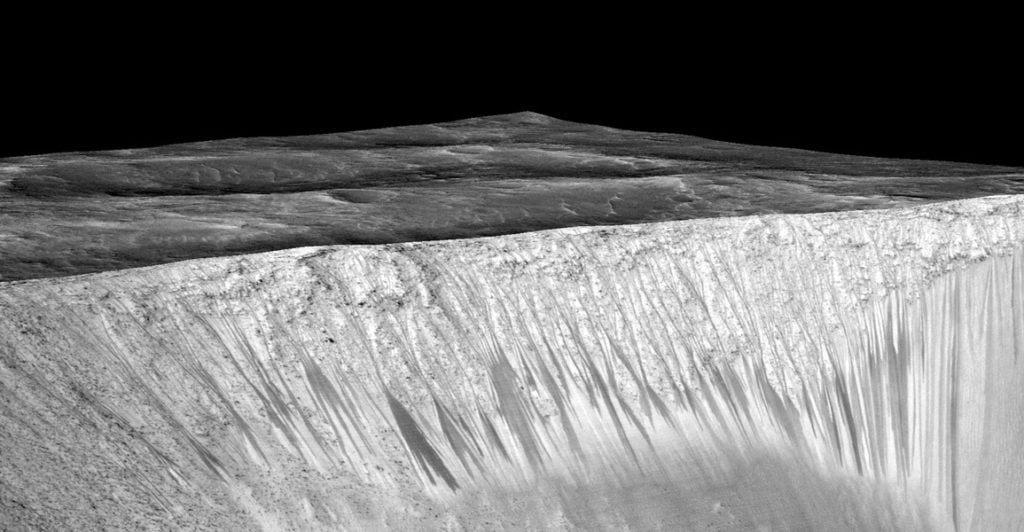

Flowing Water on Mars?

Scientists have known for years that Mars once had liquid water on its surface, and they have many contemporary examples of frozen water ice on the Red Planet. But this week NASA announced the strongest evidence yet that liquid water still flows on Mars. Researchers have observed from orbit dark line-like features called recurring slope lineae (RSL) that develop, darken, and grow seasonally in many locations on Mars. The appearance of these features coincides with warmer surface temperatures (above -23 degrees Celsius), and the lines fade again when temperatures cool. Although scientists suspected the dark lines might be related to flowing water, the evidence remained circumstantial until spectral observations of multiple sites indicated that the darker features contained hydrated salts. In other words, briny salt water is still flowing at or near the Martian surface. (Image credits: NASA)

Martian Dust Devil

This photo from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter stares almost straight down a dust devil on Mars. Like their earthbound brethren, Martian dust devils form when the surface is heated by the sun, causing warm air to rise. The rising air causes a low pressure area that the surrounding air flows into. Any rotational motion of the air intensifies as it is entrained. This is a consequence of conservation of angular momentum. Just as a spinning ice skater spins faster when he pulls his arms in, the vorticity of the inward-flowing air increases, forming a vortex. In addition to dust devils, this same physical mechanism applies to waterspouts and fire tornadoes, although the heating source for those is different. (Photo credit: NASA; via APOD)