Inspired by the roaming rocks of Death Valley, researchers went looking for ways to make ice discs self-propel. Leidenfrost droplets can self-propel on herringbone-etched surfaces, so the team used them here, as well. On hydrophilic herringbones, they found that meltwater from the ice disc would fill the channels and drag the ice along with it.

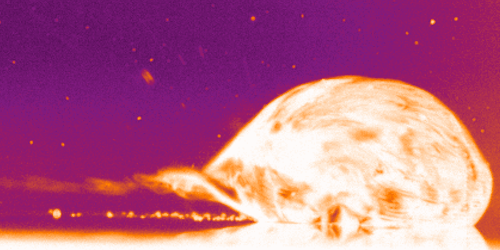

But on hydrophobic herringbone surfaces, the ice disc instead attached to the crest of the ridges and stayed in place–until enough of the ice melted. Then the disc would detach and slingshot (as shown above) along the herringbones. This self-propulsion, they discovered, came from the asymmetry of the meltwater; because different parts of the puddle had different curvature, it changed the amount of force surface tension exerted on the ice. Thus, when freed, the ice disc tried to re-center itself on the puddle.

The team is especially interested in how effects like this could make ice remove itself from a surface. After all, it requires much less energy to partially melt some ice than it does to completely melt it. (Image and research credit: J. Tapochik et al.; via Ars Technica)