In a 1959 lecture entitled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom”, Richard Feynman challenged scientists to create a tiny motor capable of propelling itself. Although artificial microswimmers took several more decades to develop, there are now a dozen or so successful designs being researched. The one shown above swims with no moving parts at all.

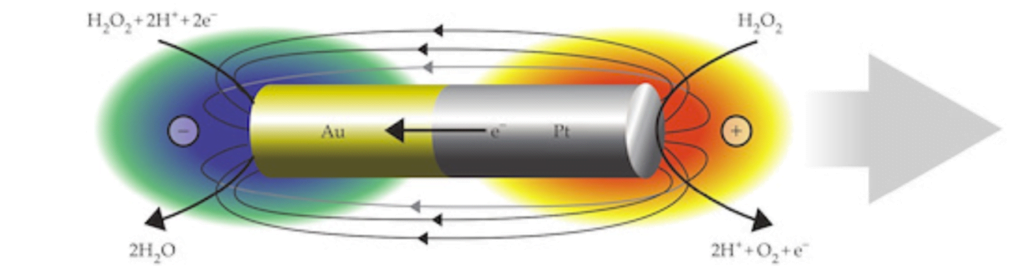

These microswimmers are simple cylindrical rods, only a few microns long, made of platinum (Pt) on one side and gold (Au) on the other. They swim in a solution of hydrogen peroxide, which reacts with the two metals to generate a positively-charged liquid at the platinum end and a negatively-charged one at the gold end. This electric field, combined with the overall negative charge of the rod, causes the microswimmer to move in the direction of its platinum end.

Depending on the hydrogen peroxide concentration, the microswimmers can move as quickly as 100 body lengths per second, and they’re capable of hauling cargo particles with them. One planned application for artificial microswimmers is drug delivery, though this particular variety is not well-suited to that since the salty environment of a human body disrupts the mechanism behind its motion. (Image credits: swimmers – M. Ward, source; diagram – J. Moran and J. Posner; see also Physics Today)