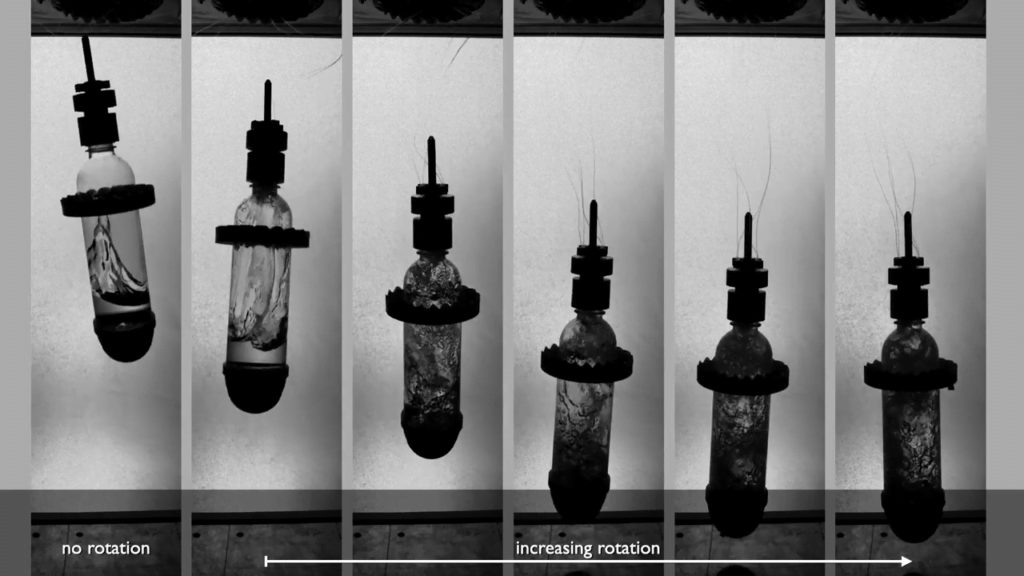

Drop a ball that’s partially filled with water and it may or may not bounce. Why the difference? It all comes down to where the water is before impact. The more distributed the water is along the walls, the less likely a container will bounce. Researchers found they could control the bounce by spinning the bottles before they dropped. Centrifugal force flings the water all over the walls of the spinning bottle, and, when impact happens, the water concentrates into a central jet. For the spinning bottles, that jet is wide, messy, and swirling; it breaks up quickly, expending energy that could otherwise go into a bounce. In effect, the spinning bottle’s jet forms quickly enough to “stomp” the rebound. (Video and image credit: A. Martinez et al.; research credit: K. Andrade et al.)

Tag: rebound

Jets from Hollows

Bubbles rising through a viscous fluid deform and interact. As they collapse into one another, the lower bubble induces a gravity-driven jet that projects upward into the higher bubble. The more elongated the bubble, the faster the jet. The same behavior is seen in the rebound of a cavity at the free surface of a liquid. The authors suggest a universal scaling law for this behavior. (Video credit: T. Seon et al.)

Splash Rebound

A ball dropped onto a puddle loses some of its rebound momentum to fluid motion. On impact, a splash curtain and radial jet form as the fluid is displaced by the ball. As the ball rebounds, the splash curtain is drawn inward into a column of fluid drawn up by the ball, reminiscent of the way cats and dogs drink. Eventually, when the gravity’s force on the fluid column overcomes the force of the ball’s inertia, the fluid column pinches off and falls back downwards, leaving the ball free to utilize its remaining kinetic energy as it flies upward. (Photo credit: T. Killian, K. Langley, and T. Truscott)