The human placenta functions as a life-support system for a growing fetus. Despite its frisbee-like appearance, the organ is packed with nearly 10 square meters of blood vessels. On the fetal side, these blood vessels form villous trees where diffusion across the placental boundary exchanges molecules with the maternal blood that fills the space between villous trees. This setup allows oxygen, glucose, carbon dioxide and other key chemicals to cross between the parent and fetus while (ideally) keeping diseases out.

But when diseases directly affect the structure of the placenta, flow to the fetus gets disrupted. The image above shows cross-sections of placental tissues, with villous trees marked in pink, under (a) preeclamptic, (b) normal, and (c) diabetic conditions. Preeclampsia is associated with reduced density of villous trees, which restricts the amount of nutrients a fetus receives and can lead to reduced growth or stillbirth. In contrast, with gestational diabetes villous trees can proliferate, causing a high resistance to flow that also affects exchanges.

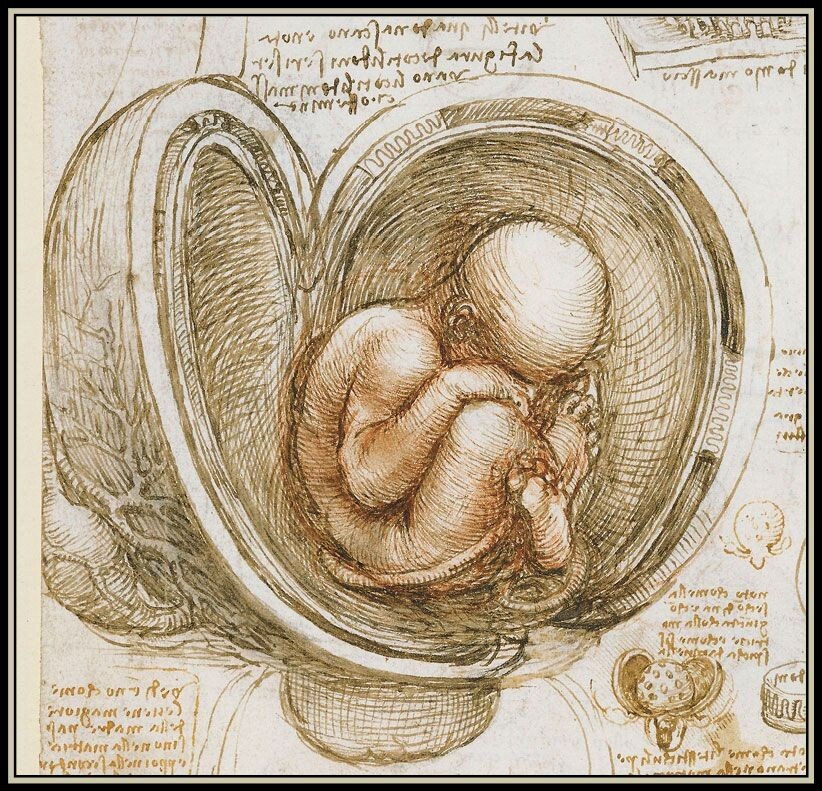

For more on the complex physics of the placenta, check out this article from Physics Today. (Image credit: sketch – L. da Vinci, placentas – A. Clark et al.; see also A. Clark et al.)