Mosquitoes, bats, and even eels use non-visual means to sense their environments. For mosquitoes, part of their obstacle avoidance comes from the exquisite sensitivity of their antennae, which are able to sense subtle changes in the air flow around them as they approach a wall or the ground. Researchers used this same technique to help a quadcopter avoid crashing by adding air pressure sensors that respond to the changes in the copter’s wake as it approaches the ground. (Image and research credit: T. Nakata et al.; via Science)

Tag: mosquitoes

Mosquito Flight

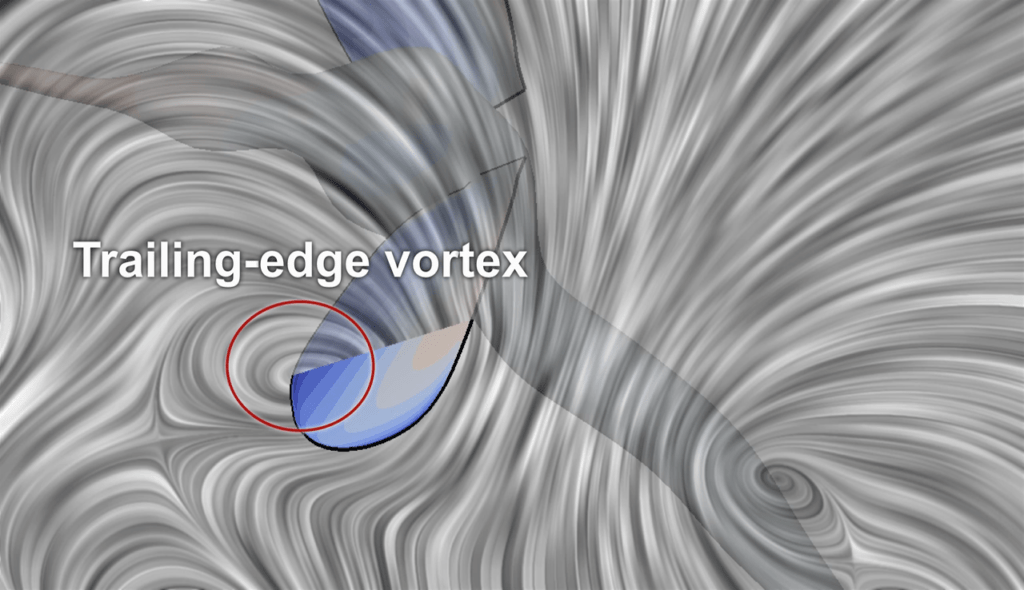

Mosquitoes are unusual fliers. Their wings are long and skinny, and they beat at around 700 strokes a second – incredibly quickly for their size. Examining how they move has uncovered some interesting mechanics. Despite their short stroke length, the mosquito generates a lot of lift on both its upstroke (when the wing is moving backward) and its downstroke (when the wing moves forward). Some features of the mosquito’s flight are highlighted in the images above. In the animation, blue indicates areas of low pressure and red indicates high pressure.

Like most flapping fliers, the mosquito generates a leading-edge vortex during its downstroke (and its upstroke). This vortex helps concentrate low pressure on the upward-facing wing surface, thereby creating lift. One of the things that makes the mosquito unique, however, is that it also creates trailing-edge vortices on both half-strokes. To do this, the mosquito rotates its wings precisely to catch the wake of its previous half-stroke. The flow gets trapped near the trailing edge of the wing and forms a vortex and low-pressure region. Like the leading-edge vortex, this low-pressure area on the upward-facing wing surface creates lift. For more secrets of mosquito flight, check out this video from Science or the original paper. (Image credit: R. Bomphrey et al., source)

How Mosquitoes Fly in the Rain

One might think that rainfall would keep the mosquitoes away, but it turns out that rain strikes don’t bother these little pests much. Because the insect is so small and light compared to a falling raindrop, the water bounces off instead of splashing. This results in a relatively small transfer of momentum, although the mosquito does get deflected quite strongly. Researchers estimate that the insects endure accelerations up to 300 times that of gravity, which is more than 10 times what a human can withstand. (Video credit: A. Dickerson et al; submitted by Phillipe M.)