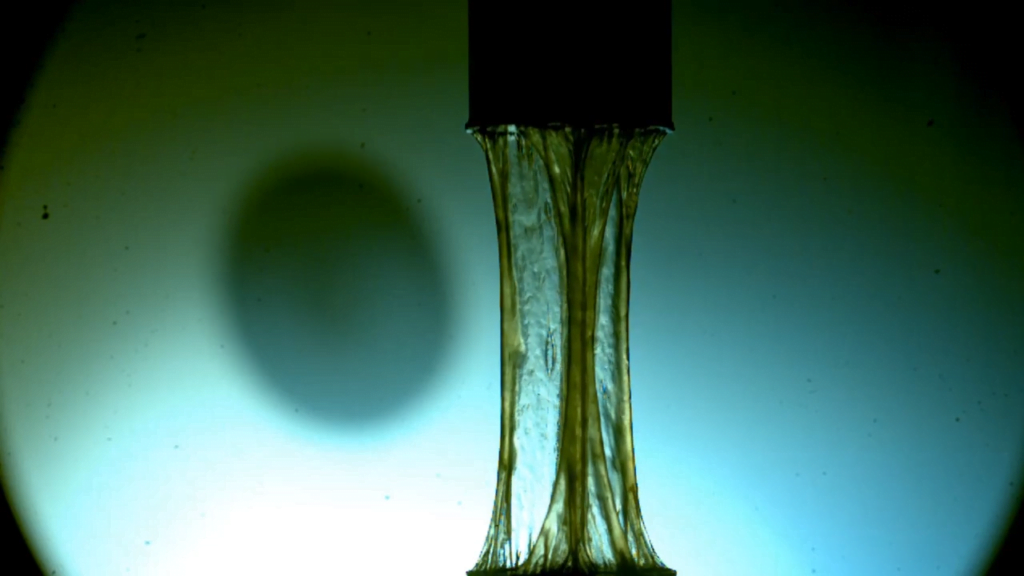

Frogs and toads shoot out their tongues to capture and envelop their prey in a fraction of a second. They owe their success in this area to two features: the squishiness of their tongues and the stickiness of their saliva. The super squishy toad tongue deforms to touch as much of the insect as possible. That shape-changing helps deliver the saliva, which is an impressively fast-acting, shear-thinning fluid. Under normal circumstances, the saliva is sticky and about as viscous as honey. But the shear from the tongue’s impact makes the saliva flow like water, spreading across the insect’s body. Then it morphs back into its viscous, sticky self, providing enough adhesive power that the insect can’t escape the toad pulling its tongue back in. (Video credit: Deep Look/KQED; research credit: A. Noel et al.)

Tag: frog

You’re Drunk, Toadlet

Most frogs and toads are excellent jumpers, taking off and landing with a control and grace that rivals elite athletes. Not so for the pumpkin toadlet. These species have become so miniaturized that the structures of their inner ears are too narrow for the fluid flow that helps frogs (and humans!) orient themselves in space. So while the toadlet certainly can jump, it careens through the air drunkenly and lands in any old direction. It’s hard not to laugh at their belly flops, somersaults, and straight-up head-first crashes. Fortunately, being so small, these landings don’t seem to hurt the toadlets, but one imagines they’re unpleasant nevertheless. Left to their own devices, the pumpkin toadlet prefers walking, slowly, like a chameleon; it might be the only way to stay within the limits of its inner ear. (Image credits: top – S. Kikuchi, others – R. Essner, Jr. et al.; research credit: R. Essner, Jr. et al.; via The Atlantic; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

How Frogs Block Unwanted Noise

In a crowded room, it can be hard to pick out the one conversation you want to hear. This so-called “cocktail party problem” is one animals have to contend with, too, when a noisy landscape can obscure the calls of potential mates. American green tree frogs have a clever solution to the problem: inflating their lungs to dampen out other frog species’ calls.

This method works because frogs have a direct anatomical connection between their lungs and their eardrums. Researchers found that when these frogs inflate their lungs, there’s a pronounced drop in their sensitivity to sound in the 1.4 – 2.2 kHz frequency band. That frequency range falls between the green tree frog’s peak mating call frequencies, but it coincides with the frequencies of other frogs living in the same regions. So rather than using their lungs to make themselves louder, these clever amphibians use them to make other frogs quieter! (Image credit: B. Gratwicke; research credit: N. Lee et al.; via Physics Today)

To Beat Surface Tension, Tadpoles Make Bubbles

For tiny creatures, surface tension is a formidable barrier. Newborn tadpoles are much too small and weak to breach the air-water surface in order to breathe. Researchers found that, instead, the 3 millimeter creatures place their mouths against the surface, expand their mouth to generate suction, and swallow a bubble consisting largely of fresh air.

When they’re especially small, some of these species are essentially transparent (Image 1), allowing researchers to see the bubble directly. But even as the tadpoles aged (Images 2 and 3) and grew strong enough to breach the surface, they observed many instances in which the tadpoles continued this bubble-sucking method to breathe. (Image and research credit: K. Schwenk and J. Phillips; via Cosmos; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh)

Singing Toads

Many male frog and toad species sing during warmer months to attract mates. Some, like the American toad in the photo above, can be heard for an impressive distance. Here’s a video of an American toad in action. To sing, these amphibians close their mouth and nostrils, then force air from their lungs past their larynx and into a vocal sac. As with human sound-making, forcing air past the frog’s larynx vibrates its vocal cords and generates noise. That noise resonates in the vocal sac, amplifying the sound and driving the ripples seen in the photo. (Image credit: D. Kaneski; submitted by romannumeralfive)